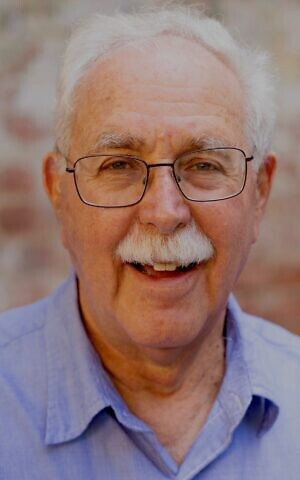

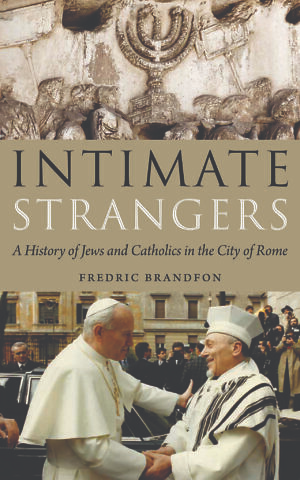

From the Church to Mussolini, ‘Intimate Strangers’ sees archaeologist and historian Fredric Brandfon explore the rich and complex history of Europe’s oldest Jewish community

When archaeologist and historian Fredric Brandfon visited the Vatican Museum, he asked his Jewish tour guide how long her family had lived in Rome. Her answer gave him a sense of the sweeping history of Jews in the Eternal City.

The tour guide’s ancestors had come to Rome following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. The family’s survival was threatened during the Holocaust. Fortunately, the guide’s grandparents were sheltered in the Vatican Museum, while her mother was hidden in a convent, placed under the care of the mother superior.

This conversation spurred Brandfon to write a book about a centuries-old relationship — recently published as “Intimate Strangers: A History of Jews and Catholics in the City of Rome.”

“I realized there was a story here that had to be told,” Brandfon told The Times of Israel.

He remembered thinking, “I am a historian, an archaeologist. Maybe I can go back a little further, I can get more information.” After researching the extensive history of Jews in Rome, Brandfon said, “By the end, I had the inception of this book.”

A press release noted the sheer expanse of the story over two millennia: “The Jewish community of Rome is the oldest Jewish community in Europe, and one with the longest continuous history, having avoided interruptions, expulsions, and annihilations since the year 139 BCE. For most of that time, Jewish Romans have lived in close contact with the world’s largest continuously functioning international organization: the Roman Catholic Church.”

The Roman Jewish narrative includes key moments in Italian history, such as the period of Rome’s notorious Jewish ghetto, which existed for over three centuries; as well as the Fascist rule of Benito Mussolini and the calamity of the Holocaust, with Pope Pius XII silent in the face of Axis atrocities.

Brandfon is a scholar of the 11th century BCE, aka the Iron Age. His latest book begins with the relatively more recent narrative of ancient Rome. The Jewish community in the empire’s capital was spared from violent repercussions following cataclysmic events in far-off Judaea — namely the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the end of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135.

Nevertheless, Rome’s landmark Arch of Titus commemorated the namesake general, emperor and conqueror of Jerusalem, and the Roman Jewish community saw its traditional financial contributions for upkeep of its temple diverted to refurbish a temple to Jupiter instead. The book also chronicles the narrative of Berenice, a Jewish queen of Judaea who lost her throne, became Titus’s lover and moved with him to Rome in 75. Upon his accession to the throne four years later, he expelled her. She is remembered in Italian culture, including in operas.

After the demise of the empire, the Catholic Church became the principal power within Rome. For much of Roman Jewish history, the community lived within the cramped environs of a notorious ghetto that was installed in 1555 by Pope Paul IV and endured longer than any other European counterpart, according to Brandfon. Although its walls were briefly taken down during the Napoleonic invasions, it did not officially end until Italian unification in 1870.

“The area chosen to be the ghetto was an undesirable area to live in — swampy, disease-infested, absolutely cramped,” Brandfon said. “And then, of course, there were restrictions on what you could do to make a living. You couldn’t do very much.”

As the papal authorities restricted Jewish lives in the ghetto, they encouraged one way to enter the wider world — conversion to Catholicism, including by force.

“In my mind, it was the darkest time in the relationship between Jews and Catholics in Rome,” Brandfon said of the forced conversions. “It was precipitated by the church’s anxiety about losing its place in the world. It’s not an excuse, it’s an explanation of what happened.” He cited “terrible stories, especially the kidnapping of children, the forced conversion of children.”

One child convert became a cause celebre in the 19th century — Edgardo Mortara, a Bolognese Jewish boy unknowingly baptized by the family housekeeper and transported to Rome. Despite protests from Jewish communities around the world, including in the United States, Mortara’s family could not get him back. He ultimately joined the priesthood and died in Belgium in 1940.

By then, the Roman Jewish community was facing the menace of Fascism under Mussolini and his alliance with Hitler’s Third Reich.

Initially, after Mussolini seized power in 1922, his position on Jews seemed much less hostile. He occasionally encouraged Zionism, although he recommended Jews settle not in Palestine but Ethiopia, where he aimed to create an Italian colony. Mussolini also had a Jewish mistress, Margherita Sarfatti, who proved ideologically influential to Il Duce, according to the author.

“Margharita Sarfatti used to write Mussolini’s speeches,” Brandfon said. “She got him an apartment in Rome. He could live with her, move there, apart from his family. She was instrumental in formulating whatever Fascism was supposed to be… Whatever theory was behind Fascism in Italy to a great deal came from her part.”

However, Il Duce shifted to vehemently antisemitic policies in the Race Laws of 1938, limiting Jewish participation in public life to their minuscule percentage of the population.

“In any government agency or administrative position, they would be almost nonexistent,” Brandfon said, adding that escape from Italy became impossible: “At a certain point, there was no place for Jews to go. The world was at war.”

During World War II, Pius XII did not speak out against Mussolini or Hitler, with his actions subsequently becoming a source of controversy.

Calling Pius’s wartime conduct “a very difficult subject,” Brandfon said, “I do not believe he was an antisemite. I do believe he was in a terrible situation.”

“What I say in the book is that he had a reputation that he self-promoted as a very spiritual man. I believe he did not live up to his spiritual reputation when it came to the Holocaust and the Jews of Rome — and the Poles of Poland, too. He did not speak out about Catholics in Poland being slaughtered by Nazis. He did not speak about innocents being killed in turmoil. He did not speak about innocent Jews,” he said.

When the Allies invaded Sicily in 1943, the situation in Rome got worse for the Jews: Mussolini’s government fell, a power vacuum ensued, and the Nazis took over the city. Despite initial objections from some Nazis, the new overlords rounded up over 1,000 Roman Jews for deportation to Auschwitz, with only 15 surviving. What finally saved the remainder of Rome’s Jews was the Allied liberation of the city, which took place 80 years ago this past June.

Looking for reasons other than antisemitism to explain the pope’s behavior, Brandfon noted a communique from the Vatican ambassador to Mussolini’s puppet regime in northern Italy. The ambassador cited a policy of neutrality out of fear of Nazi reprisals for speaking out.

“[Pius] could have been thinking, if I speak out, there will be reprisals against Catholics and Jews [hiding] in churches, monasteries and convents in Rome, Italy and Europe,” Brandfon said. “There’s no evidence, but he might have.”

During the Nazi occupation, despite official Vatican silence, some Catholics sheltered Jews, while others turned them in for deportation and death. The list of betrayers even included a Jewish female gangster nicknamed la Pantera Nera or the Black Panther.

“Catholics, Jews, whatever it is, you can’t generalize,” Brandfon said. “There were good ones, bad ones, and everything in between… There’s always going to be some horrible story you’re going to condemn. The reverse is also true.”

A more hopeful period began in the postwar years. On December 2, 1947, following the UN vote supporting the establishment of the State of Israel, Rome held a celebration — ironically, at the Arch of Titus. Pope John XXIII, who as Cardinal Angelo Roncalli had helped save Jews during WWII, took a wider step as pontiff, holding the Second Vatican Council. After his death in 1963, his successor, Paul VI, continued the council, which is remembered for the Nostra Aetate declaration, which cleared Jews of collective guilt for the death of Jesus Christ.

However, Italy showed reluctance to prosecute ex-Nazis and onetime collaborators for wartime crimes against Jews, and when the Catholic Church sought to address its own conduct during the Holocaust, the ensuing document totaled three pages. Historians found this woefully inadequate — including David Kertzer, who penned a book about the subject, “The Popes Against the Jews,” and went on to write another book, on Pius XII, “The Pope at War.”

Recent popes, including Francis, have had more fruitful relationships with Rome’s Jewish community leaders, such as Chief Rabbi Riccardo di Segni.

“Under [Pope John Paul II’s successor], Pope Benedict XVI, there continued to be outreach to the Jewish community,” Brandfon said. “The present chief rabbi of Rome, he met Pope John Paul II, he met Benedict XVI, he met Francis… There is hope, there is hope. I’m a hopeful guy in general.”

As reported by The Times of Israel