David Dayag, a self-taught astronomer, is getting attention for his time-lapse photos, showing the fire and fury at the center of the solar system as if it were next door

A self-taught astronomer in the coastal city of Netanya is dazzling viewers around the globe with his close-up, time-lapse photos of the sun.

David Dayag, who goes by Deddy, has been showing off his 30-second clips of the sun all over social media, offering fiery glimpses of the star as few have seen it before.

Dayag, 39, isn’t the first astrophotographer to photograph the sun. But he’s among the first to take photos from this angle and depth.

On forays out in the Negev desert to stare at the skies, Dayag was told by fellow astronomers that he couldn’t photograph the sun, that it just wasn’t possible.

Dayag, however, doesn’t usually take no for an answer.

“People tend to do what they’re told to do,” said Dayag of his telescopic activity. “I have to understand why.”\

“A lot of people don’t want to explore by themselves,” he added.

By studying his telescope and playing with how much light and speed were necessary to capture images of the sun, Dayag eventually managed to prove the doubters wrong.

“It’s all about how much light enters the filter of the telescope,” he said.

While trying to take pictures of the sun without proper equipment can destroy lenses or damage eyes, specialized filters and other appurtenances are not hard to come by.

Dayag’s first photos were captured using a 150mm Cosmos refractor and Daystar quark H-Alpha filter on a Celestron AVX mount, combined with a ZWO asi178mm camera. That initial footage, from January 2021, depicted clearly two enormous sunspots, which were seen in 30-second-long, time-lapsed photos.

“It boggled everyone’s mind,” said Dayag.

Dayag was far from the first to capture photos of the sun — the field goes back some 150 years. But he believes he was the first to do so with a time lapse.

“People take pictures of the sun,” he said. “I had to understand why it was only done a certain way. I wanted to understand if it could be done differently.”

Dayag’s photos, which offer a close-up view of the sun’s filaments and spots, rely on how much light enters the telescope’s filter, and the use of a longer telescope to offer bigger and better resolution of the sun. He tends to photograph the sun early in the day when it’s more active, exhibiting more sunspots and texture.

“I fell off my chair when I saw all those filaments and sunspots,” he said. “And saw that the telescope could handle it.”

A lifelong amateur astronomer, Dayag isn’t averse to teaching himself new tricks.

For most of his 39 years on this planet, Dayag has tried to figure things out for himself, particularly when it comes to stargazing.

He discovered telescopes as a child when his grandfather came across a book about how to build a telescope, roughly translated from another language into Hebrew.

“I read it about 30 times over,” said Dayag, but even then he couldn’t put his own telescope together because some of the necessary materials weren’t readily available in Israel back then.

He was also inexperienced in building something as complex as a telescope, and his family couldn’t afford to send him to specialty afterschool programs or buy expensive equipment.

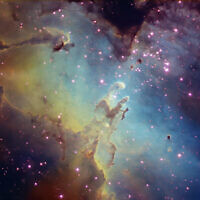

But he continued to gaze at the night sky, wondering about the celestial bodies, and had a special fascination for supernovas, seeking to understand what made the star explode and what was happening inside the superheated mass.

“Even before I had a telescope, I would just stare up at the sky,” he said.

Dayag’s high school agreed to buy a lens for him, allowing him to finally build his own telescope from plumbing parts and the new lens, offering a view of the skies above.

He’d place it on his bed or a chair and point it out the window, maybe homing in on a line in the clouds or a glint in the sky.

“It really moved me,” he said.

Dayag described himself as a lover of the sciences — biology, chemistry and physics — but he struggled to stay interested in school unless motivated by the subject matter.

“I would only go to ten percent of my classes, I would get to school late, but I did well in the classes I loved,” he said.

It was only after the army, when Dayag, lacking a university degree, began working in software development for a variety of startups that he earned enough money to finally buy his first telescope.

He now has a small collection of them carefully shelved in his Netanya home, next to his home music studio and his home office.

“Music focused me emotionally,” said Dayag, who taught himself guitar and drums in school. “Stargazing is my passion.”

He continues to work in tech, plays in two progressive rock bands and about once a month heads off to the desert towing a kitted-out trailer that includes solar panels to charge all of his star-gazing equipment.

Dayag thinks about pursuing a Ph.D. in physics, but worries about the rigors of academia. Other dreams include flying to another star and living alone on Mars.

And if Elon Musk’s spacecraft manufacturer SpaceX offered him a job, Dayag would not hesitate to pack up his telescopes and leave Netanya.

“I’d do that in a second,” he said.

As reported by The Times of Israel