Analysis of charcoal from Tel Tsaf dig reveals olive and fig tree wood, indicating first examples of orchards by an advanced, wealthy society

The first domestication of fruit trees anywhere in the world took place some 7,000 years ago in the Jordan Valley, according to a joint study by Tel Aviv University and Jerusalem’s Hebrew University.

The researchers reached their conclusions after analyzing charcoal remains at the Chalcolithic Tel Tsaf site in the Jordan Valley and finding wood from olive and fig trees. Olive trees do not grow naturally in the area.

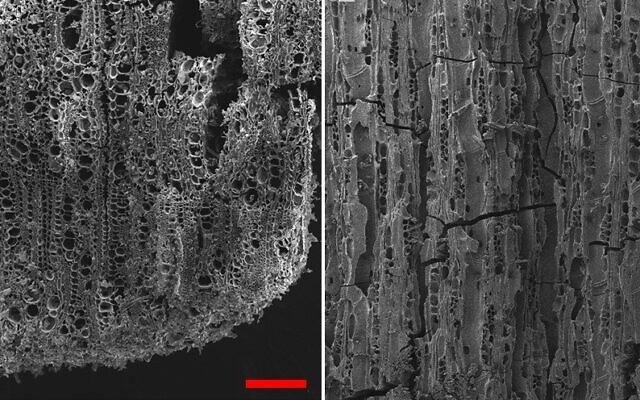

Dr. Dafna Langgut, head of Tel Aviv’s Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Ancient Environments, which specializes in microscopic identification of plant remains, said it was possible to identify trees by their anatomic structure even if they had been burned down to charcoal.

“Wood was the ‘plastic’ of the ancient world,” she said. “It was used for construction, for making tools and furniture, and as a source of energy. That’s why identifying tree remnants found at archaeological sites, such as charcoal from hearths, is a key to understanding what kinds of trees grew in the natural environment at the time, and when humans began to cultivate fruit trees.”

Langgut’s analysis of the charcoal from Tel Tsaf found locally native trees, but also olive and fig.

“Olive trees grow in the wild in the land of Israel, but they do not grow in the Jordan Valley,” she said. “This means that someone brought them there intentionally — took the knowledge and the plant itself to a place that is outside of its natural habitat.”

“In archaeobotany, this is considered indisputable proof of domestication, which means that we have here the earliest evidence of the olive’s domestication anywhere in the world.”

Langgut also identified remnants of branches belonging to the fig tree, which did grow naturally in the Jordan Valley.

As the fig tree had little value for firewood or working into tools or furniture, she concluded that the branches resulted from pruning, a method still used today to increase a fruit tree’s yield.

The charcoal remnants were collected by Prof. Yosef Garfinkel of Hebrew University’s Institute of Archaeology who directs the excavations at Tel Tsaf.

“Tel Tsaf was a large prehistoric village in the central Jordan Valley, south of Beit Shean, inhabited between 7,200 and 6,700 years ago,” Garfinkel explained.

“Large houses with courtyards were discovered at the site, each with several granaries for storing crops. Storage capacities were up to 20 times greater than any single family’s calorie consumption, so clearly these were caches for storing great wealth.”

“The wealth of the village was manifested in the production of elaborate pottery, painted with remarkable skill. In addition, we found articles brought from afar: pottery of the Ubaid culture from Mesopotamia, obsidian from Anatolia, a copper awl (a small pointed tool used for piercing holes, especially in leather) from the Caucasus, and more,” he said.

Langgut and Garfinkel were not surprised to discover that the inhabitants of Tel Tsaf were the first in the world to intentionally grow olive and fig trees, since growing fruit trees is evidence of luxury, and this site is known to have been exceptionally wealthy, the joint university press release said.

“The domestication of fruit trees is a process that takes many years, and therefore befits a society of plenty, rather than one that struggles to survive,” said Langgut.

“Trees yield fruit only three to four years after being planted. Since groves of fruit trees require a substantial initial investment and then live on for a long time, they have great economic and social significance in terms of owning land and bequeathing it to future generations — features that suggest the beginnings of a complex society.”

“Moreover, it’s quite possible that the residents of Tel Tsaf traded in products derived from the fruit trees, such as olives, olive oil, and dried figs, which have a long shelf life. Such products may have enabled long-distance trade that led to the accumulation of material wealth, and possibly even taxation — initial steps in turning the locals into a society with a socio-economic hierarchy supported by an administrative system,” she said.

Langgut said that in addition to the eveidence of early fruit tree cultivation, they had also discovered some of the earliest examples of stamps, suggesting the beginnings of administrative procedures.”

“As a whole, the findings indicate wealth, and early steps toward the formation of a complex multilevel society, with the class of farmers supplemented by classes of clerks and merchants,” she said.

The latest research was published earlier in May in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports from the publishers of Nature.

As reported by The Times of Israel