Nicholas Winton helped organize Kindertransports that carried young people to safety on the eve of war. ‘Nicky & Vera’ by author and illustrator Peter Sis now honors his legacy

When Vera, a young Jewish girl, was growing up outside of Prague in 1938, she had little on her mind besides her grandmother and love of animals. But her blissful childhood would change forever with the emerging crisis brought about by her country’s neighbor, Nazi Germany.

When Vera’s parents learned about an opportunity for Jewish children to escape to the United Kingdom organized by an Englishman named Nicholas Winton, they sent their 9-year-old daughter on a train out. Ultimately, 669 Jewish children were saved by the series of transports out of Czechoslovakia.

Winton, who kept quiet about his role, was surprised on live television decades later as fellow members of the studio audience revealed themselves to be children whose lives he helped save.

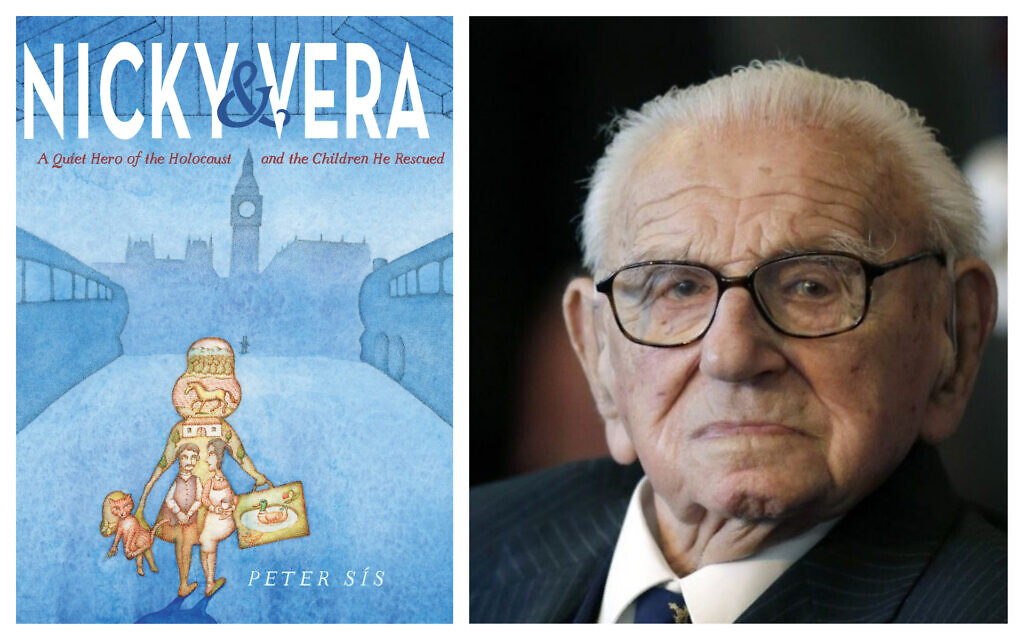

Winton, lived a long life, dying in 2015 at the age of 106 and now his moving narrative is being told in “Nicky & Vera,” a new book by award-winning children’s author and illustrator Peter Sis, released earlier this year. The book has been named to a summer reading list for children by The Times and The Sunday Times.

Collectively, those saved became known as “Winton’s Children” — one of whom, Vera (Diamantova) Gissing, is the real-life protagonist of the book. Winton saved others who would go on to be noteworthy achievers, including British politician Alfred Dubs (Baron Dubs), geneticist Renata Laxova and a co-founder of the Israel Air Force, Hugo Marom, who was born in Brno, the same hometown as Sis.

“Winton’s Children” are part of a wider story of the Kindertransports in which Jewish child refugees from Nazism came to the UK.

Taught to act quick, he saved lives

Sis, who now resides in the United States, was visiting his former homeland with his son in 2009 and happened upon a celebration of Winton’s 100th birthday in Prague.

Sis himself became a refugee later in life, fleeing his then-communist country for the US while working on a film project during the Olympics nearly 40 years ago. He has become a multiple Caldecott honoree and recipient of a MacArthur fellowship, with previous titles about Galileo, Charles Darwin and Tibet.

After Sis set out to write a book about Winton, he was aided by another chance discovery: Gissing’s memoir about her escape from Czechoslovakia.

“I’m trying to bond for younger audiences,” Sis told The Times of Israel in a recent interview. “There’s the contrast of the life of a little girl, the danger of coming, the expectations, in the time of great uncertainty.”

In the character of Winton, he said, “My objective from the beginning was to show someone… who asked, ‘How do I help someone when I see something wrong, say this is wrong and do something about it?’”

Before Winton was a rescuer, he was an Olympic-level fencer. In masterly strokes, Sis depicts his upbringing. Winton was born into a family of Jewish descent that converted to Christianity. He received a broad education before going into finance. The protagonist is whimsically illustrated in his fencing uniform riding a pigeon during university days.

Winton originally planned to devote the winter of 1938 to another physical activity — skiing. Yet a friend named Martin Blake urged him to come to Czechoslovakia instead, to help deal with the refugee crisis that followed the Anschluss and Kristallnacht — both shown in grim illustrations.

“He, because of who he was, moved very, very quickly,” Sis said.

Part of a movement

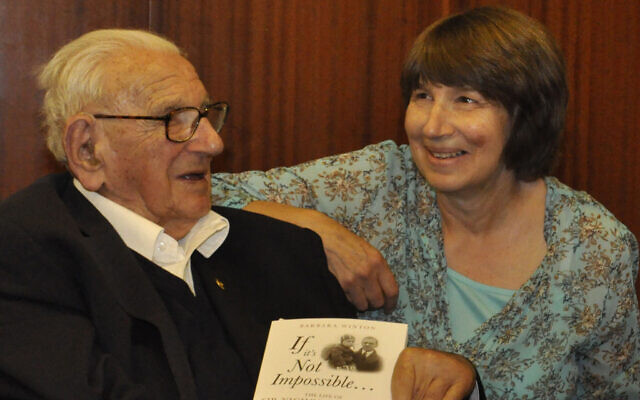

The author notes that there were many others in Czechoslovakia who helped refugees. This point was also mentioned by Winton’s daughter Barbara Winton and by historians.

“He couldn’t possibly have done it himself,” said Barbara Winton, author of a biography of her father. “Somebody had to be in Prague organizing the trains” and assisting with other components of the project in Czechoslovakia and beyond, from “lists of children, briefing parents, organizing foster homes in the UK.”

“A lot of people were instrumental,” Winton said, naming fellow Britons Trevor Chadwick and Doreen Warriner, adding that Warriner’s work landed her on Hitler’s watch list. “He was part of a group of people. He was the one who took on responsibility when the Czech Kindertransport happened, getting the permits. He was a kind of catalyst. There were all kinds of individuals before him who got him to get involved.”

“I knew Nicholas Winton was a hero,” Sis said. “Because he also lived a long life, he became the face of something. He became almost a mythical hero who somehow saved all these people. I found out there were other young people around him — Chadwick was one — a whole team.”

“In the afterword,” he said, “I do mention [other rescuers, including Chadwick and Warriner]. Everybody can do their own research as they get interested. As many [people] came to Prague, of course you can see many other organizations planning to help people — Americans, Christians, Jewish organizations.”

Laura Brade, a scholar at Albion College in Michigan, called Winton “really part of a constellation of actors who came to Prague in the aftermath of the Munich agreement.”

According to Brade, in Prague, Winton connected with Warriner, the chairwoman of the British Committee for the Refugees of Czechoslovakia, who showed him refugee camps.

“He forms a partnership with her,” Brade said. “He decides he can be useful… helping organize the transport of children.”

After three weeks in Prague, Winton had to go back to his job as a stock trader by the end of January 1939.

In London, Brade said, Winton, his mother and a small staff “took care of permits, visas, payments to the Home Office to allow children to come to England, of course working with Czech committees as well. The Prague-based Jewish refugee committee was very involved with the children… It was really a collaborative effort.”

‘Troublesome Sainthood’

Brade expressed concern that some individuals involved in the rescue have been left out of the narrative. She and fellow scholar Rose Holmes wrote a 2017 article about this subject, “Troublesome Sainthood.”

“We tried to untangle all the actors involved in the rescue,” Brade said.

“There really were a lot of women involved — Czech women, British women, who actually stayed in Prague, doing a lot of really dangerous work assisting refugees in Nazi-occupied Bohemia and Moravia,” which became a Reich protectorate in 1939.

“One of the things that happened was that women were typically placed in very different roles,” Brade said. “They were not necessarily the public face of the organization. But they did a lot of work on the ground. They were written out of the story.”

So were accused communists, she said.

“Warriner was accused later of having communist ties,” said Brade. “She was interrogated by the British government. People with questionable political histories, political leanings, were also sort of written out of the story — Doreen Warriner, Trevor Chadwick, Czech women like Marie Schmolka, Hannah Steiner. All died by the time Winton’s story gained a lot of public traction in the ‘80s.”

As the rescued children entered their golden years, they understandably welcomed “finally having somebody to thank,” Brade said. “I think that played a role in focusing on one person as the hero.”

She called Winton “clearly a very generous, giving individual, modest… He himself was an admirable individual that we all want to live up to, should live up to.” She also said, “I think Barbara Winton’s book does a really great job with how these other people became involved,” and although she has not read “Nicky & Vera,” “it’s on my list of things to read. I love Peter Sis’s work.”

Asked what made Nicholas Winton do what he did, she replied, “I would love if we could answer that question. I would be much more hopeful.”

“There’s the fact he had a friend who goes [to Czechoslovakia] first and says, ‘You should come see what’s going on here,’” Brade said. “And then I do think he’s the kind of person who, when he encountered a situation like this, and had felt able to do something, I think he was motivated to act… [If I knew] what motivates altruistic people to do what they do, we would have a very much different world.”

She noted that the Czech Jewish community suffered “incredibly” during the Holocaust, with about 88% of the country’s Jews slain.

Some of the rescued children, including Vera, returned to Czechoslovakia after the war and found that their families had perished.

“It was a terrible ordeal to lose their families,” Sis said, “building completely new lives.”

Yet they went on to become adults — in England, Israel, the US, in some cases Czechoslovakia, although it became harder after the 1948 communist coup — and have children and grandchildren of their own, including in Vera’s case.

“I spoke to her daughter,” Sis said. “She has grandchildren and an extended family.” He added that while COVID-19 travel restrictions have kept his communications with Vera online, “I would very much like to meet Vera and also her family, the families of other [rescued] children.”

“Now there’s a generation of people, of course in their 90s,” Sis said. “There’s less and less of them left. It’s an absolutely fascinating sort of tragic story.”

As reported by The Times of Israel