A must-read novel for fall, ‘The Lost Shtetl’ by first-time fiction writer Max Gross offers fable inspired by the great Yiddish writers that comforts and challenges in corona times

The Holocaust always fascinated author Max Gross. But while reading incessantly about the Nazis’ notoriously efficient genocide of the Jews, one thought kept niggling at him: He wondered whether they could have just possibly missed a Jewish village somewhere in Eastern Europe. And if so, what would have happened?

Gross, 41, imagines a possible answer to this question in his terrific debut novel, “The Lost Shtetl,” published October 13.

Growing up in New York, he would ride the subways reading books on World War II, including biographies of Adolf Hitler. “When I got a Kindle, people on the subway finally stopped thinking I was a Nazi,” he joked to The Times of Israel in a recent interview.

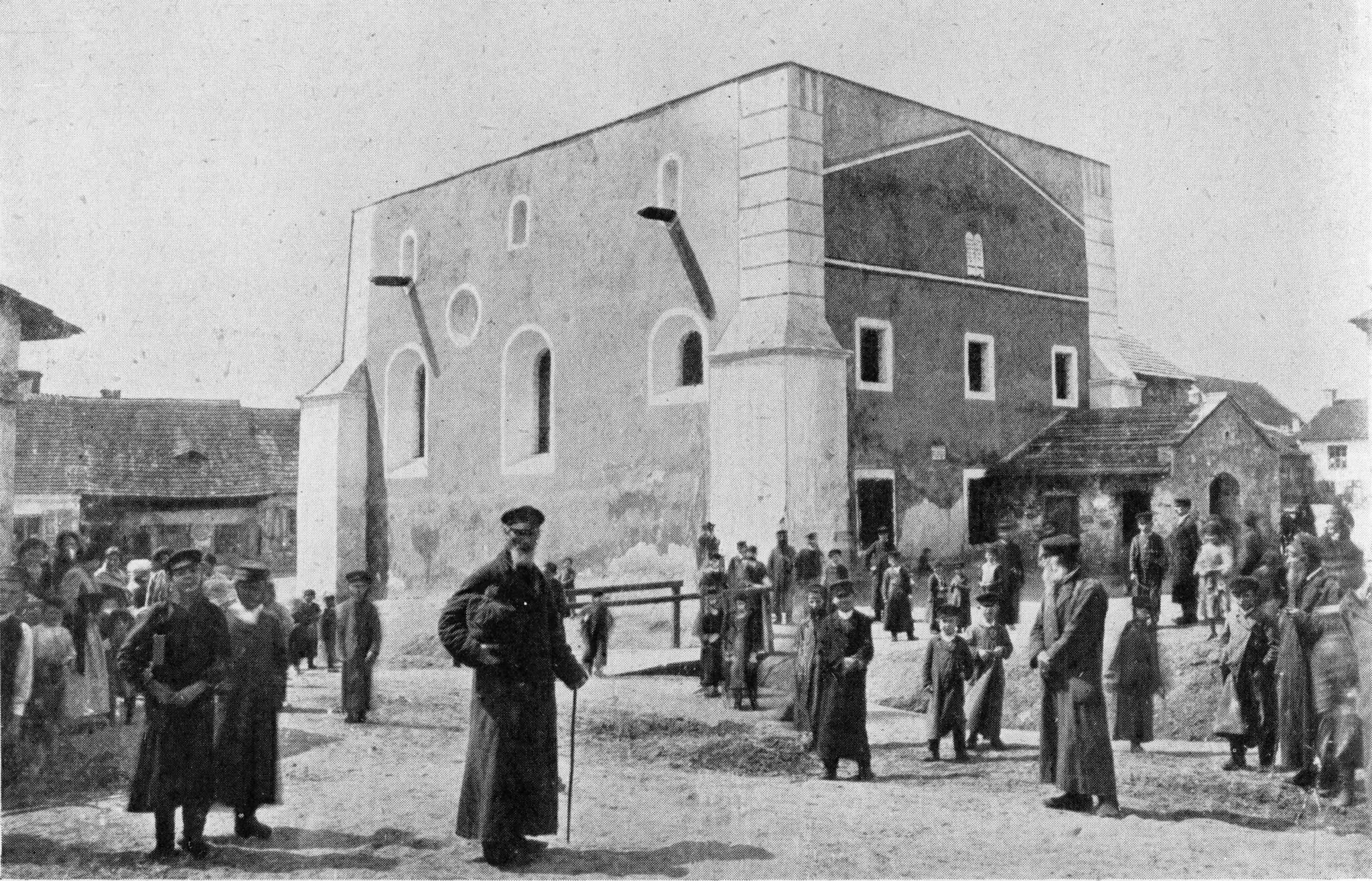

All that reading paid off in the realistic touches within the fabulism of “The Lost Shtetl.” Here we have a fictional Polish shtetl called Kreskol that was inexplicably passed over by the Nazis. Life carries on in Kreskol undisturbed as it did a century ago. However, when a newly divorced couple disappears, unforeseen events lead to a disturbing awakening for the town’s inhabitants.

Having been cut off from the rest of the country and the world (no spoilers about the how, when and why), the people of Kreskol emerge into modern-day Poland with no knowledge of the Holocaust, the establishment of the State of Israel, or the Cold War. They have never seen an automobile, telephone or computer.

Such a tale would be in danger of devolving into a silly Wise Men of Chelm story were not for Gross’s excellent writing and the serious philosophical questions underlying the novel’s multilayered narrative.

In an interview with The Times of Israel, Gross pointed to the greats of Yiddish Literature as inspiration.

“I was obsessed with Isaac Bashevis Singer when I was in high school. I have also read a lot of Shalom Aleichem‘s work. I wanted the narrator to be in that tradition,” Gross said.

“It’s a voice that is both of the shtetl and of the modern world looking back at it,” he added.

Gross, editor-in-chief of the real estate publication Commercial Observer, got his start in journalism at the Forward. There, he used to patiently field regular calls from the widow of famous Yiddish writer Chaim Grade, who would kvetch that her husband’s work did not get the respect she believed it deserved from the the paper.

Gross said he regrets he cannot read Yiddish literature in the original and must rely on English translations.

“I’m Pesha when it comes to languages,” he said, likening himself to the runaway divorcée in “The Lost Shtetl” who, although young, cannot pick up a second language — even when her life depends on it.

Gross, who lives in New York and is now a married father, is also the author of “From Schlub to Stud: How to Embrace Your Inner Mensch and Conquer the Big City,” a combination memoir/dating guidebook that was sparked by his uncanny resemblance to comedic actor and producer Seth Rogen. However, he always worked at trying to produce fiction, including while at an arts fellowship program in Arad, Israel, in 2000-2001.

The idea for “The Lost Shtetl” came to him a decade ago, and at first he thought it would make for a good short story. But as Kreskol became a fully realized universe within Gross’s mind, he came to understand that he had a novel on his hands.

“I had a first draft of the book in 2014, and when Trump was elected in 2016 I was very depressed and I stopped being a news junkie. I got focussed and used my time to finish the novel,” Gross said.

“The Lost Shtetl” starts as Pesha and her ex-husband go missing. Kreskol’s rabbis send a teenage baker’s assistant named Yankel to the nearest city to find them. The “bastard” Yankel is the obvious candidate for this dangerous task, as his unwed mother is dead and he has no other close family who would miss him if he were to become prey for the animals of the surrounding forest.

After some time, Yankel returns to Kreskol without the missing couple. Instead, he arrives with government officials and the media in tow. Kreskol has been discovered and life there will never be the same. Things will also change drastically for Yankel, when he decides to stow away on a media helicopter and escape to Warsaw to start a new life in modern-day Poland. In the capital, Yankel runs into the runaway Pesha.

The narrative essentially toggles between Yankel and Pesha’s gritty existence in modern day Poland, and life back in Kreskol following its discovery by the Polish authorities and public. Yankel and Pesha learn — among other things — that not everyone likes Jews as much as they do back home. And as often happens in Jewish communities facing change, Kreskol divides into acrimonious factions.

Although there is humor throughout “The Lost Shtetl,” it turns darker once knowledge of the Holocaust seeps into the consciousness of the people of Kreskol.

“The Lost Shtetl” deals with a clash of civilizations, and the prices people are willing to pay — or not — to live in the modern world. It also raises important questions about the singularity of the Holocaust, and the place of Jews in Poland today.

Gross, however, was quick to emphasize that he is not offering judgement about the Jewish community in current-day Poland, where he visited about six years ago while doing research for the book.

“I think the questions that are raised are for Jews in the Diaspora in general. I think it is just more fraught in Poland,” he said.

“Poland changed a lot politically while I wrote the book,” Gross added, referring to the significant rise in rightwing populism in the country.

When Gross began writing “The Lost Shtetl” eight years ago, he could not have foreseen how much its main themes would resonate with readers living through an isolating pandemic.

Literary critic and author Daphne Merkin recently wrote that the novel’s “dose of fabulism may be the best cure yet for a psychologically intolerable contemporary moment.”

Indeed, the cleverly written “The Lost Shtetl” is full of magical realism and laugh-out-loud humor that transport readers far from ill-fated 2020. But at the same time, it is replete with serious philosophical questions that leave us pondering long after reading the last page.

“The Lost Shtetl” makes one think about the pros and cons of the living in today’s world of global communication — and global pandemics.

Gross leaves readers to decide for themselves whether or not they want to wear rose-colored glasses. He, however, most definitely knows where he stands.

“One of the afflictions of modernity is nostalgia, which is almost always false,” he said.

As reported by The Times of Israel