Running through September, a new exhibit shows off the work of the Jewish Expressionist painter who gave up small-town life in the Pale of Settlement, only to die in Vichy France

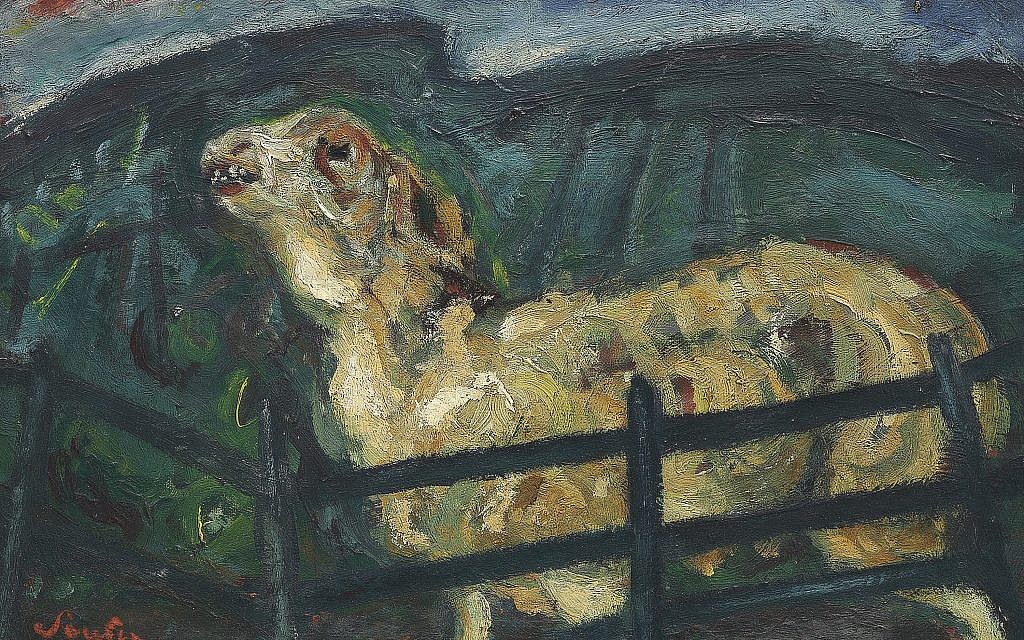

NEW YORK — A splayed carcass and delicately wrought feathers; shimmering herring and a bleating lamb. Each canvas seems to capture the space between life and death, stillness and movement.

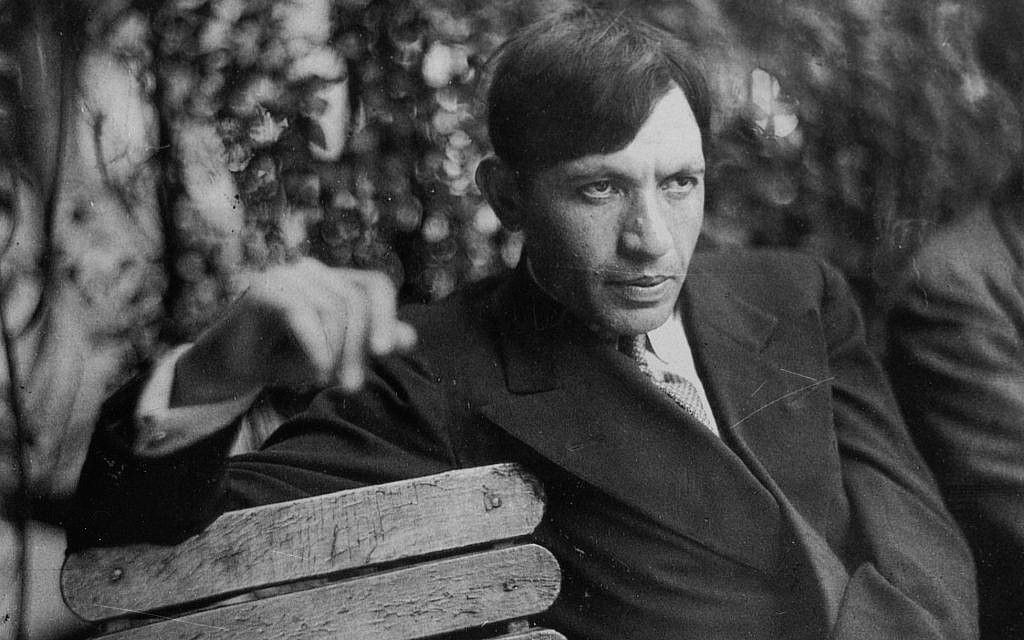

For many of his 50 years the Jewish artist Chaim Soutine, too, occupied a space between. As a young man in the shtetl he was once beaten for painting. As a painter in Paris he faced discrimination for his religion. He lived in Montparnasse during the bohemian heyday, yet he so preferred the solitude of the Parisian countryside he eventually moved there.

This liminal space Soutine occupied for much of his life is now on display through September 16 at New York’s Jewish Museum in “Chaim Soutine: Still Life.”

“He was a complicated character. He was to a certain extent a loner. He did of course have friends; you couldn’t live that café life as a hermit. But he started living outside of the city and his life alternated between alienation and isolation,” said Stephen Brown, the Neubauer Family Foundation associate curator at the Jewish Museum.

The 32 paintings of hanging fowl, beef carcasses and raw fish are considered among the Expressionist artist’s greatest achievements, revealing how he pushed the limits of traditional still life painting.

Rather than a bowl of glistening berries resting on a lacy tablecloth, or a plump duck carcass hanging on a peg, his paintings suggest dislocation, hunger and life. Each canvass is painted in sumptuous tones of reds and blues, greens and browns.

Soutine was the second-youngest of 11 children born to a tailor in Smilavichy, a Jewish shtetl in the Pale of Settlement (now Belarus). Violence often visited the region; during his childhood thousands of Jews were murdered in pogroms.

While Soutine’s parents weren’t averse to their son’s artistic inclinations — the source of which remains a mystery — the shtetl was less than enamored with the idea. After Soutine painted the village rabbi, the rabbi’s sons beat him severely.

While Soutine’s parents weren’t averse to their son’s artistic inclinations — the source of which remains a mystery — the shtetl was less than enamored with the idea. After Soutine painted the village rabbi, the rabbi’s sons beat him severely.

His mother sued the rabbi’s family and Soutine took 25 rubles from a financial settlement to go to Minsk, where he was to be apprenticed to a tailor. He soon left for Vilna where he enrolled in art school, Brown said.

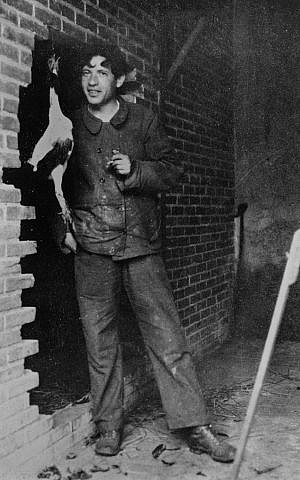

A few years later, in 1913, the then 20-year-old moved to Paris. There he spent time with other Jewish émigré painters including Amedeo Modigliani, who became a mentor of sorts. In the Louvre he studied countless paintings and drew inspiration from Rembrandt, Goya, Chardin and Courbet.

For nearly 10 years he toiled, getting a commission here and there. His fortune changed in 1922 when he found a patron in Albert C. Barnes, the art collector.

“Barnes was crucial to Soutine’s story. In some books it’s referred to as the ‘Barnes Miracle,’” Brown said.

Barnes had been collecting prior to World War I and when he returned to Paris after the war he was looking specifically for works executed by a contemporary artist. While visiting a dealer he noticed a painted portrait of a pastry chef. He demanded to meet the artist. After being introduced to Soutine, Barnes bought more than 50 paintings.

“That transformed Soutine financially and professionally. He became a prince of a painters,” Brown said.

Over time Soutine influenced a new generation of artists, including Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, as well as Frank Auerbach, Cecily Brown and Damien Hirst.

Brown conceived of the exhibit together with consulting curators and Soutine scholars Esti Cunow and Maurice Tuchman, authors of “Chaim Soutine (1893-1943).”

Divided into four sections, “A Modern Still Life,” “Fowl,” “Flesh” and “The Life of Beasts,” the exhibit presents works from Soutine’s early years in Paris through the early 1940s.

The first section, “A Modern Still Life,” shows how Soutine considered gesture, material and color as important to the work as the subject. One can visualize the artist paint covered fingers and hands applying thick layers of paint on the canvass.

In these paintings, Soutine seems to focus on capturing the moment between life and death. It was a fixation that developed throughout his work of the 1920s.

“The works are aggressive, brutal and uncompromising. They are a testament to his personal tragedy and the 20th century, even though he didn’t paint war or battlefields,” Brown said.

“Flesh” features almost portrait-like images of a single animal. To execute the 1925 painting “Flayed Ox,” Soutine restaged Rembrandt’s “The Flayed Ox” in his studio. This let him work from direct observation rather than simply copying the masterpiece. This wasn’t the first time Soutine recreated a still life scene from one of the Old Masters.

He was known to fill his studio with dead fowl, rabbits and beef carcasses to use as subjects. The odors emanating from his studio were so foul his neighbors called the police. From then on Soutine used formaldehyde to mask the scent. However, because the chemical dulled the colors of the carcasses he took to splashing blood on them.

Of course much of what is known about Soutine comes from oft-repeated anecdotes.

“It’s difficult to gauge what is true about Soutine because the sources we usually go to for an artist, such as journals and correspondence, don’t exist. A kind of mythology arose about him. You have to somehow judge the anecdotes told about him,” Brown said.

The exhibit ends with “The Life of Beasts.” Here the viewer encounters several paintings from the late period of Soutine’s life when he fled to the countryside west of Paris at the outbreak of World War II and German occupation of France.

With their more muted tones, the small paintings of animals on display here hint at a vulnerability that is particularly poignant considering Nazi Germany’s threat to the world situation and of course to Soutine’s own life.

The style of “The Duck Pond at Champigny,” painted in July 1943 a month before Soutine’s death from a stomach ulcer, is a return of sorts to the outdoor landscapes he did decades before.

“We have just 32 paintings on display, but it’s a banquet really. I hope some who know Soutine already will see him in a different light,” Brown said.

As reported by The Times of Israel