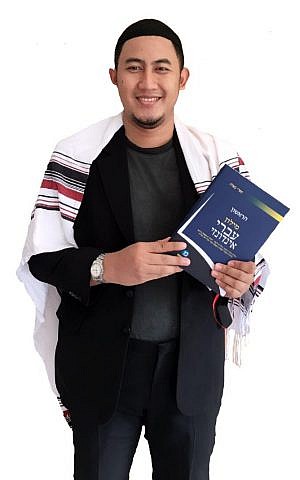

While some criticize effort to promote language, Sapri Sale’s previously published Hebrew-Indonesian dictionary received endorsement from senior imam

A Sunni Muslim man recently opened the first-ever Hebrew course in Indonesia, a Muslim-majority country that has no formal ties with Israel and where Hebrew is generally seen as the language of the enemy.

Sapri Sale, who last year published the first Hebrew-Indonesian dictionary, says it is mostly Christians who are interested in his courses but he expects Muslims to increasingly become interested in learning the language as well.

“My activities are not only teaching Hebrew but [also an effort] to minimize the negative stigma about Israel and Hebrew in Indonesia,” he told The Times of Israel in an email interview. “Many Indonesians don’t understand the real circumstances” of the Middle East conflict, but based their anti-Israel views “solely on their solidarity to Palestinian people,” he said.

While some of his countrymen have criticized the promotion of Hebrew, Sale has also received warm endorsements even from unexpected quarters, including senior religious figures.

The ultimate objective of his work is to “build a bridge of communication between two countries, Indonesia and Israel, in order to promote dialogue and mutual understanding,” he said.

Last month, Sale, 52, opened two classes at the Indonesian Conference on Religion and Peace headquarters in central Jakarta. Some 20 students study Mondays and Wednesdays for an hour and a half, with the goal of being able to understand basic Hebrew at the end of the eight-week course.

“My students are from different backgrounds — Muslim, Christian and others, but mostly Christian,” he said. “My prediction in the future is more Muslim students will joint my classes, due to similarity of Hebrew and Arabic [because] Hebrew is easier for them to learn.”

Most of his students are simply interested in learning about a new culture and language they usually have little access to, he said. Some of his Christian pupils joined the course because they want to be able to read the Bible in its original language, he added.

Until recently an employee at Jet Asia Airways, Sale has been interested in Israel and Hebrew since the early 1990s, when he was a student of Arabic literature at Cairo’s prestigious Al-Azhar University.

The “negative stigma” of the Jewish state in the Arab world didn’t make sense to him and he became curious to find out more. His efforts started with a Hebrew course at the Israeli Academic Center in Cairo, which the Academy of Science and Humanities had set up after the 1979 peace treaty.

Sale, who was born in Palu City in Central Sulawesi, and grew up in Malang, a small city in East Java, studied Islamic tradition in a conservative Islamic school. In 2006, he started working on the first-ever Hebrew-Indonesian dictionary, which was published a decade later and has more than 35,000 entries.

The dictionary — called Milon Rishon — has been warmly received by some churches, seminaries, students, and four Islamic State universities, he said, adding that several hundred copies have been distributed to Muslim and Christian communities in Indonesia. One of the country’s most senior imams has also endorsed the dictionary and even posed for photos while holding the book (Sale asked for the imam’s name not to be disclosed).

In addition to the dictionary, Sale is working on other books geared at promoting Hebrew in his home country. One is a 150-page basic conversation guide for Indonesian visitors to Israel. The other books are about Hebrew grammar.

“I believe this endeavor will pave the way for the realization of dialogue between two nations,” he said.

In Indonesia, the country with the world’s largest Muslim population, Hebrew is still largely frowned upon, especially by those who reject any rapprochement with Israel. Jerusalem and Jakarta never had formal diplomatic relations. Israeli officials have spoken of clandestine links and called for the establishment of formal ties, but have been rebuffed by the Indonesian government.

Sale, who has been to Israel only once, says the government has so far not reacted in any way to his promotion of Hebrew. Officials may say something at some point, as his activities pick up steam, but he does not expect serious repression.

However, he has been attacked by ordinary Indonesians, mostly Islamic hardliners, he said. “They accused me of being a henchman or a spy.”

Hebrew is the language of the enemy, some of Sale’s critics charge, but he usually replies that Hebrew is an important language and should not be equated with the policy of a particular state.

“I teach Hebrew to make people learn about Israeli culture and technology,” he said, “just as we learn about Japanese or other languages and nations — to study their culture and technology.”

As reported by The Times of Israel