She came to symbolize what was ultimately acceptable and what was not, at a time when that cardinal distinction is being challenged in democracies other than Britain as well

How could an elderly woman, presiding over a profoundly dysfunctional family and living in the lap of luxury at the taxpayers’ expense, possibly have served as a bulwark against the erosion of democracy?

Well, maybe that’s too grand a claim to make on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II. Maybe it is even a stretch to suggest that her presence at the helm of the monarchy, her rectitude and unfailing civility over an astonishing 70 years, may have given Britain’s elected leaders pause, curbed some of their excesses.

But the additional layer of the monarchy under this matriarch, ceremonially presiding over the political fray, credibly helped Britain retain its self-perception of doing the right thing, upholding traditional positive values, and therefore made it a better place than it would have been without her.

With her death, the monarchy — its purpose, legitimacy, value — will be tested and reassessed. Though here too, this fascinating figure — somehow retaining a measure of mystique despite being ubiquitous and relentlessly scrutinized — has performed a crucial service, giving her successor a far greater prospect of success than could have been imagined not many years ago.

After Lady Di, the former Princess of Wales, was killed in that Paris tunnel car crash fleeing paparazzi 25 years ago, her adulterous former husband was a widely despised figure and support for the institution of royalty was plummeting. A survey in 2000 found less than half of respondents supporting the assumed process by which Charles would become king when his mother died or abdicated, with a third advocating that the throne skip a generation to Prince William.

By staying around for another quarter-century, the queen — herself at her lowest hour in underestimating public grief over the death of the “People’s Princess” (©Tony Blair) — provided enough time for Charles to significantly rehabilitate himself. Enough time, too, for Camilla Parker Bowles, the new king’s first love and second wife — “there were three of us in this marriage,” Diana memorably told the BBC — to gain acceptance, be trusted with the title “Queen Consort,” and even see their relationship hailed as a modern love story in (admittedly outlying) newspaper columns this week.

Even Queen Elizabeth, however, could not prevent the deep staining of the royal brand by some of its other players, and most especially the ignominy caused by her third child. Prince Andrew earlier this year paid millions to settle a sex abuse suit brought against him in the US by Virginia Giuffre, who had alleged that she was trafficked to Andrew by Jeffrey Epstein.

In terms of her public duties, the queen rarely put a foot wrong over those seven long decades of endless appearances and interactions, exuding calm, restraint and civility, with more than occasional humor, wisdom and subtlety.

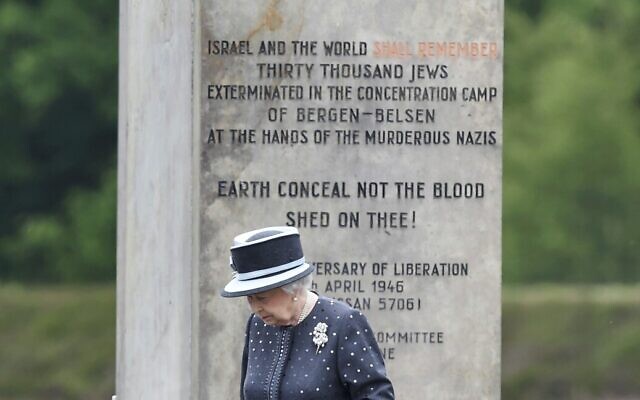

No, she didn’t visit Israel. Nor did she apologize for Britain’s legacy of colonialism: As an Associated Press feature opened this week, “Upon taking the throne in 1952, Queen Elizabeth II inherited millions of subjects around the world, many of them unwilling.” Hers was a ceremonial office after all; there were limits beyond which she could not defy the Foreign Office in particular and government in general.

She is believed to have tussled privately, however, over policy and direction with some of her prime ministers. She was also said to sometimes publicly intimate private sentiment about hosting certain foreign dignitaries through the creative use of jewelry (including wearing a brooch from the Obamas on the day the Trumps arrived for a visit in 2018).

And she happily participated not only in a James Bond comedy stunt for the 2012 London Olympics but also, with a doubtless well-understood symbolism, in a sketch just this year acting alongside a refugee with no table manners but endless good intentions: Paddington Bear.

As the screenwriter Frank Cottrell-Boyce, centrally involved in both those sketches, so beautifully put it this week, “Paddington is an evacuee, a refugee, one-time prisoner, pretty much every category of need that is mentioned in Matthew 25. Here, he is being welcomed with tea and good manners. This is a strong statement of a set of values that are not uncontested in the corridors of power. To have them exemplified so joyfully at such a moment meant something.”

Three years ago, prime minister Boris Johnson gave her what was subsequently determined to be unlawful advice to suspend Parliament — a move that was seen by critics as designed by Johnson to minimize MPs’ scrutiny of his government’s Brexit plans. Johnson was forced to relinquish the premiership earlier this month, ousted by his own party; he might well have gone sooner had it been determined that he had, unthinkably, lied to the queen.

At once distant and ever-present, the queen tried to serve as a focal point for British unity and decency and whatever Britons would like to consider to be British values for 70 years. If she was numbed or exhausted or unhappy about the job, she rarely if ever showed it.

Truss is Britain’s prime minister on the strength not of a national vote, nor even an election among Britain’s members of parliament, but on the votes of 81,326 members of the Conservative Party.

British democracy is certainly not perfect. But the queen did play a positive role in its functioning, because she came to symbolize what was ultimately acceptable and what was not.

At a time when that cardinal distinction is being sorely challenged, in democracies other than Britain as well, she will be missed.

As reported by The Times of Israel