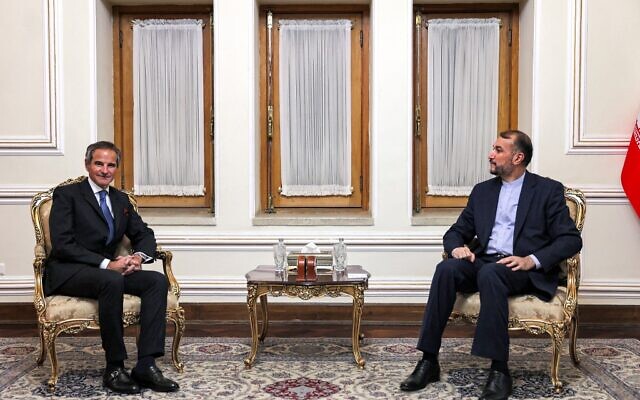

Rafael Grossi, head of UN nuclear watchdog, warns Tehran that there is no way around inspectors, says world currently only getting ‘blurred image’ of country’s nuclear program

ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — The head of the United Nations nuclear watchdog warned Tuesday that the restrictions faced by his inspectors in Iran threaten to give the world only a “very blurred image” of Tehran’s program as it enriches uranium closer than ever to weapons-grade levels.

Speaking in a wide-ranging interview to The Associated Press, Rafael Mariano Grossi said he wanted to tell Iran that there was “no way around” his inspectors at the International Atomic Energy Agency if the Islamic Republic wanted to be “a respected country in the community of nations.”

“We have to work together,” Grossi said from a luxury hotel in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates, after he visited that country’s first nuclear power plant. “They must work together. I will make sure they understand that in us they will have a partner.”

Grossi’s insistence that the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) remained “an auditor” for the world came as negotiations falter in Vienna to revive Tehran’s tattered nuclear deal. Hours earlier, the chief of Iran’s civilian nuclear program insisted his country would refuse the agency access to a sensitive centrifuge assembly plant.

That plant in Karaj came under what Iran describes as a sabotage attack in June. Tehran blamed the assault on Israel amid a widening regional shadow war since former United States President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew America from Iran’s landmark nuclear accord with world powers. Iran since has refused the IAEA access to replace cameras damaged in the incident.

“If the international community through us, through the IAEA, is not seeing clearly how many centrifuges or what is the capacity that they may have… what you have is a very blurred image,” Grossi said. “It will give you the illusion of the real image. But not the real image. This is why this is so important.”

Grossi dismissed as “simply absurd” an Iranian allegation that saboteurs used the IAEA’s cameras in the attack on the Karaj centrifuge site. Tehran has offered no evidence to support the claim, though it’s another sign of the friction between inspectors and Iran.

Since the nuclear deal’s collapse, Tehran has started enriching uranium up to 60 percent purity — a short technical step from weapons-grade levels of 90%. The deal limited enrichment to 3.67%, enough to be used in a power plant. The nation’s stockpile of enriched uranium grows every day far beyond the scope of the 2015 accord, which saw Tehran agree to limit its nuclear program in the exchange for the lifting of economic sanctions. It also spins ever-more advanced centrifuges also barred by the deal.

While stressing he wasn’t involved in the political negotiations ongoing in Vienna, Grossi acknowledged the advances made by Iran since the deal’s collapse meant there would have to be change to the original agreement.

“The reality is that we are dealing with a very different Iran,” he said. “2022 is so different from 2015 that there will have to be adjustments that take into consideration these new realities so our inspectors can inspect whatever the countries agree at the political table.”

And while Iran insists its program is peaceful, US intelligence agencies and the IAEA have said Iran ran an organized nuclear weapons program until 2003.

“There’s no other country other than those making nuclear weapons reaching those high levels” of uranium enrichment, Grossi said of Iran. “I’ve said many times that this doesn’t mean that Iran has a nuclear weapon. But it does mean that this level of enrichment is one that requires an intense verification effort.”

Iran’s mission to the United Nations did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Grossi’s remarks.

In Vienna, however, anxiety is growing among European nations at the negotiating table. The US has remained outside of direct talks since abandoning the accord.

“Without swift progress, in light of Iran’s fast-forwarding of its nuclear program, the [deal] will very soon become an empty shell,” they warned in an overnight statement.

Apparently responding to the criticism, Iranian negotiator Ali Bagheri Kani wrote on Twitter: “Some actors persist in their blame game habit, instead of real diplomacy.”

But the Iranian negotiators who have entered the talks for the first time in months under newly-elected hard-line President Ebrahim Raisi have taken maximalist positions. Bagheri Kani himself described six previous rounds of negotiations with a team under former President Hassan Rouhani as a mere “draft.”

Asked about the difference between the two administrations, Grossi said that “the change is palpable.”

“The president himself and people around him have been saying very clearly they have views about the program,” he said. “They have strong views about the interactions that Iran has been having” with both the IAEA and parties to the nuclear deal.

He also described cooperation with the Raisi administration as “slower than expected.”

“We have been able to start this relationship quite late I would say,” Grossi said.

Meanwhile, satellite photos obtained by the AP show ongoing construction in the mountain south of Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility, twice the target of suspected Israeli attacks. Another above-ground facility is being built at Iran’s underground Fordo facility, which also has begun uranium enrichment amid the Vienna talks in defiance of the nuclear deal.

Grossi said Iran has informed the IAEA about the ongoing construction and his inspectors “are following” progress at the sites.

Regionally, Saudi Arabia has begun exploring nuclear power. Unlike the UAE — which has a strict agreement with the US that ensures it doesn’t enrich its own uranium — Saudi Arabia says it wants a centrifuge program. That opens the risk of nuclear proliferation as the kingdom has threatened to rush for a nuclear weapon if Iran obtains one. Grossi described discussions between Riyadh and the IAEA as “very positive.”

And in Israel, long believed to be a nuclear-armed state, a massive construction project continues at its secretive nuclear reactor near Dimona, which isn’t subject to the IAEA’s watch. Iran often points to Israel’s weapons program as an international double-standard given the scrutiny of Tehran’s civilian program.

When asked about Israel, Grossi said: “I think the international community would like every country to sign up to the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons and to put all the facilities under safeguards from the IAEA.”

He stressed the importance of ensuring that IAEA inspectors have the unfettered ability to monitor and access Iran’s fast-accelerating nuclear program.

“The problem is that the more time passes and you lose the ability to record what is going on, then the moment this capability is restored, inspectors come back and start to put the jigsaw puzzle together again,” he said. “There might be gaps. And these gaps are not a good thing to have.”

As reported by The Times of Israel