Bucharest, Romania – “It’s relentless — relentless,” sighed nurse Claudiu Ionita, standing in front of a line of gurneys in Bucharest University Hospital’s morgue. On each gurney lay a body inside a black plastic bag.

The morgue has a capacity for 15 bodies, but on the day CNN visited, it had received 41. The excess bodies filled the corridor outside, while wails echoed from within the morgue. A woman had been allowed inside for a final glimpse of her father.

Bucharest University Hospital is the Romanian capital’s largest medical facility treating Covid-19 patients and is struggling through the country’s fourth wave, its worst yet.

“I never thought, when I started this job, that I would live through something like this,” said Ionita. “I never thought such a catastrophe could happen, that we’d end up sending whole families to their graves.”

Several floors above, all the beds but one in the hospital’s now-expanded intensive care units were full. A nurse was changing the sheets on the one vacant bed — empty, because the person who occupied it now lay in the morgue.

Romania has one of Europe’s lowest vaccination rates.

Just under 36% of the population has been vaccinated, even though the country’s vaccination campaign got off to a good start last December.

Medical workers and officials attribute this low vaccination rate to a variety of factors, including suspicion of the authorities, deeply held religious beliefs, and a flood of misinformation surging through social media.

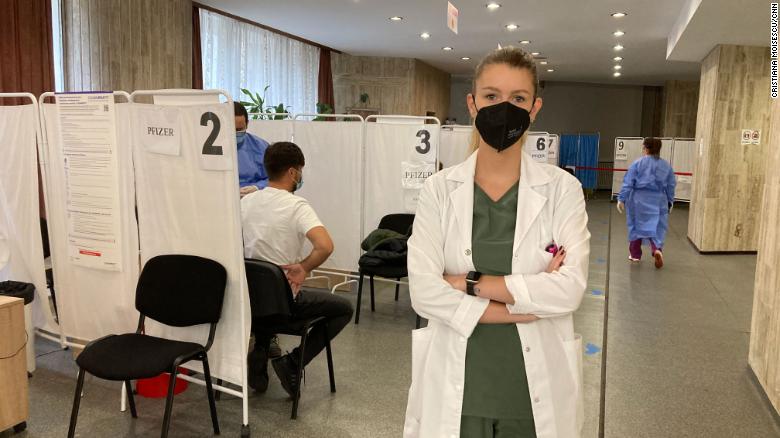

When Dr. Alexandra Munteanu, 32, arrived for duty at one of Bucharest’s vaccination centers after an overnight shift in hospital, she found turnout was low. She’s perplexed that the gravity of the disease just doesn’t seem to have sunk in. “There are lots of doctors, myself included, who work with Covid patients, and we are trying to tell people this disease actually exists,” she said.

One of the country’s most vocal and high-profile anti-vaxxers is Diana Sosoaca, a member of the Romanian Senate. In one of her many public stunts she tried to block people from entering a vaccine center in her constituency in the northeast of the country.

“If you love your children, stop the vaccinations,” she says in a video clip on her Facebook page. “Don’t kill them!”

The vaccines on offer in Romania have been extensively tested for use in children and have proven to be safe and effective, but that hasn’t stopped her and others from spreading wild rumors on social media and local television.

Officials and medical personnel are exasperated that public figures have done so much to undermine their efforts.

“Look at the reality,” said Col. Dr. Valeriu Gheorghita, an army doctor who runs the national vaccination campaign. “We have our intensive care units full of patients. We have lots of new cases. We have, unfortunately, hundreds of deaths every day. So this is the reality. And more than 90% of patients who died were unvaccinated.”

In Bucharest, a huge banner has gone up, covering half the façade of a building on a major boulevard. “They’re suffocating. They’re begging us. They’re regretting,” are the words printed in massive black letters above black-and-white photographs of medics struggling over Covid patients in an intensive care unit.

Down below, few passers-by glance up at the poster, and even fewer cared to share their thoughts with CNN. Soon, however, that banner will go up in other major cities in the country.

“There’s manipulation,” said a woman who gave her name only as Claudia, adding: “Some people don’t believe in the vaccines.”

Mayor: ‘It’s not a safe vaccine’

Nowhere is that suspicion more apparent than in the countryside, where Covid-19 vaccination rates plummet to about half of those in urban areas.

Suceava County, an hour’s flight northeast of Bucharest, has the lowest overall vaccination rate in the country.

Here, the manager of the main hospital, Dr. Alexandru Calancea, 40, talks about the particularity of this region, where he was born and bred.

“This county is very religious. This is an area that has a strong religious tradition, and a lot of religious people. […] Very few [priests] are pro-vaccine, and I definitely know some who are anti-vax. Most of them choose not to say anything, either for or against.

We have proof, from the hospital, from patients who come from the same religious communities, where their priest, or their pastor, has advised them to not get vaccinated, just like that.”

Just outside Suceava, in the village of Bosanci, such a pastor also serves as the village mayor. Neculai Miron has been one of the most vocal anti-vax public figures in the country, and today is no different.

“We’re not against vaccination, but we want to verify it, to satisfy our worries, because there have been many side effects,” he told CNN. “We don’t think that the vaccine components are very safe. It’s not a safe vaccine.”

The medical data doesn’t sway him, and neither does the local GP, whom he took the CNN team to see.

Dr. Daniela Afadaroaie administers the vaccine to about 10 people every other day, using the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. The latest official records show that just under 11% of the village was vaccinated as of early November 2021.

While she talked about the situation in the village, the mayor, Miron, hovered around the doctor’s desk, peering down at the papers on her desk to see who had been vaccinated.

“When are you going to get vaccinated, Mr. Mayor?” asked Afadaroaie, laughing.

“I don’t need to get vaccinated,” he shot back. “I’m perfectly healthy.” The doctor’s explanation that the vaccine helps keep you that way fell on deaf ears.

Pastor: ‘I believe what I see, rather than what I hear’

In rural villages like this, poverty and lack of education, together with local leaders’ personal influence and traditional religious beliefs, can make for a deadly combination.

But the local Pentecostal pastor, Dragos Croitoru, insisted he was unaware of any deaths from Covid-19 in the parish. “Here in the church, we don’t have any cases of people who are sick with coronavirus. We have a zero percent mortality rate, I don’t know anyone who’s died of coronavirus here in our parish. And I believe what I see, rather than what I hear,” he said.

Despite hearing from CNN about the bodies of Covid-19 victims filling the morgue at Bucharest University Hospital, Croitoru was unconvinced. “Bucharest is bigger than Bosanci, as far as I know,” he chuckled. “We haven’t had any dead. Maybe we’ve had a few people who have been ill in the village, yes, as far as I know, yes. But the mortality rate in our church has been zero.”

The mortality rate is certainly high elsewhere in this mostly rural county. Suceava ranked third highest in Covid-19 mortality rates for the whole country as of early November, according to figures from the Public Health Unit, which monitors deaths.

A corner of the main cemetery in Suceava, the county seat that’s about 10 minutes from Bosanci, is full of freshly dug graves. In the cemetery’s chapel, a service is underway. On the hill behind the chapel, mourners gather for a funeral. Nearby, another grave is being prepared.

The wooden crosses over each new grave don’t indicate the cause of death, so it’s unclear how many died from the virus. A man working on one of the graves, however, said the number of people being buried of late was far higher than usual.

“Eternal regrets,” reads a ribbon draped across one of the graves.

Back in the morgue of the Bucharest University Hospital, a medic hammered a nail into a wooden coffin. A colleague sprayed the coffin with disinfectant.

For those who die of Covid, there will be no open-casket funerals.

“The vaccine means the difference between life and death,” said Ionita, the nurse. “People should understand that. Maybe in their last hour they should understand that.”

For those shrouded in the black body bags before him, it is already too late.

As reported by CNN