In new docuseries, Rick Rubin and the ex-Beatle don’t rehash the lore. Instead, they head to the tapes, isolating instruments and harmonies, finding outtakes, unearthing stories

NEW YORK — One thinks about the eternal songs of the Beatles, foundational to nearly 60 years of popular culture, not so much as being created by mortals, but handed down from Sinai. As Paul McCartney himself says in the spectacular new series “McCartney 3,2,1” (streaming on Hulu in North America and on Disney+ in Europe), “At the time I was just working with this bloke called John. Now I look back, and I was working with John Lennon.”

Luckily, the burdensome shadow of myth hasn’t clouded his memory. McCartney is one of only two people still living who can claim witness to these recordings that, for many of us, feel as if they’ve always been there. Even people who don’t care much about music know “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Yesterday” and “Yellow Submarine” as much as they do nursery rhymes. For those of us who have poured over everything from the Beatles’ shortest song (“Her Majesty” at 0:25) to their longest (“Revolution 9” at 8:20) as if they were passages of scripture, this documentary is a true gift.

Wisely, all involved in its creation know that there is no shortage of films that tell the story of the Beatles or Paul McCartney. Online, we can easily pull up footage from the Ed Sullivan Theater, the last gig atop Apple Records on Savile Row, or even rent the film “Give My Regards To Broad Street.” (That last one isn’t exactly recommended.) So what you get in “McCartney 3,2,1” is exactly what all music nerds fantasize about doing: sitting down with Paul and the tapes, with a piano and guitar in reach, and asking questions almost just about the songs.

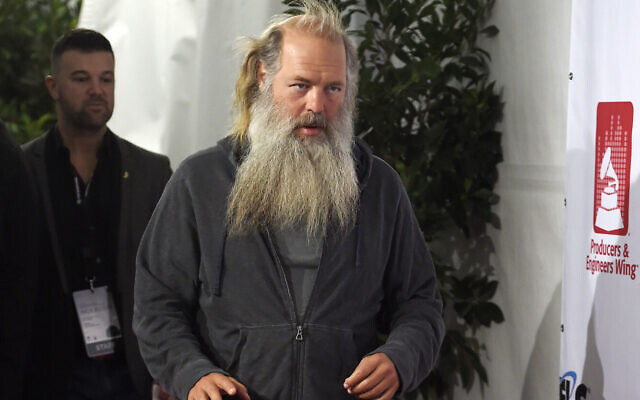

Our interlocutor is the esteemed Jewish-American record producer Rick Rubin. The 58-year-old, who famously started Def Jam Records out of his New York University dorm room (Weinstein Hall, the one with the best dining options), and who has created work with artists across the spectrum of music from rap (Run D.M.C.) to heavy metal (Slayer) to country (Johnny Cash) and everything in between (Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the Beastie Boys, the Mars Volta, Neil Freaking Diamond, etc.), is absolutely the guy you want needling McCartney with specific “How exactly did you accomplish this?” questions.

You can tell Rubin is a genius by the way he presents himself: an absolute schlump, as my mother would say, shoeless, in shorts and an ill-fitting t-shirt. His formidable size, wild hair, and rabbinical beard create the picture of the ultimate “Bear Jew,” but as you watch him listen to the isolated harmonies on “This Boy” or the guitar solo on “And Your Bird Can Sing,” he becomes like all of us: a fan of this remarkable music.

Rubin’s familiarity with the material is part of what makes this project so special. Yes, the biggest hits from McCartney’s catalog are in here, but also some of the deeper cuts. In addition to “Yesterday” and “Eleanor Rigby” and the Wings track “Band on the Run,” there are lesser-known selections like “Waterfalls” from Paul’s 1980 solo album “McCartney II.”

Also, it’s not just about the songs Paul wrote. There’s plenty of discussion of “John songs” and “George songs,” and McCartney seems genuinely touched listening back to the work of his old chums. (Ringo — the most cinematic Beatle — gets his share of fond memories as well.)

As we jump from song to song (in no particular order I could glean), Rubin takes control of a mixing board to focus on specific tracks. Since he’s celebrating McCartney, there’s a lot of attention to his innovative bass guitar playing, and with some surprising results. I’ve heard the song “Dear Prudence” 900 times, and only now do I know that what I always thought was a percussion marimba in the mix is actually Paul plucking away at the treble end of his instrument. (This is one of many delightful examples; all I want in life is to have Rick Rubin ride the faders up and down on all my favorite songs.)

What may be a revelation to some is the work of what any reasonable person would call The Fifth Beatle, at least in the context of these recordings: producer George Martin.

Here was a guy who didn’t just set the microphone levels and press record, but was an active author in creating the songs we’ve come to love.

It was his idea — to pick just one story — to add a string section to “Yesterday,” even when McCartney himself balked. He took Paul’s improvised scat singing and transformed it into a Bach-like orchestral break that sends “Penny Lane” into the stratosphere. And it was his understanding that the Beatles’ primary fear was boredom which led to the innovative use of loops and musique concrète in “Tomorrow Never Knows” (which was always my favorite Beatles song when I was hanging out at Weinstein Hall.) Time and again as McCartney answers Rubin’s questions about how the sausage was made, he responds, “That was George.” Then, after a beat, adds “Martin,” to differentiate from Harrison.

While “McCartney 3,2,1” can boast being “just about the music,” these conversations do lead to biographical anecdotes. A few were new to me, like how McCartney’s “Michelle” grew out of a tune he used to sing while pretending to be French at art parties to pick up girls. It was also great to hear McCartney recall seeing the Godfather of Afrobeat, Fela Kuti, perform at the Africa Shrine in Lagos, with his first wife, the Jewish-American photographer Linda. (The two were there to record Wings’ “Band on the Run” album; he also details how the demo tapes were stolen at knifepoint, but it may have ultimately been a blessing.) I also barked, “Oh, you’re kidding me!” back at my TV when I learned that “Sgt. Pepper” owes its name to a misheard request to “pass the salt and pepper.”

“What is there possibly left to learn about the Beatles?” you may have asked when you saw this series advertised. And that’s exactly the point. There’s nothing that’s new. But there’s still buried treasure in what’s left behind.

As reported by The Times of Israel