The US and UK will be sharing technology and expertise with Australia to help it build nuclear-powered submarines as part of a newly-announced defense pact between the three countries. The move has sparked fury in France, which has lost a long-standing agreement to supply Australia with diesel-powered subs.

But it’s not only the French who are furious. Anti-nuclear groups in Australia, and many citizens, are expressing anger over the deal, worried it may be a Trojan Horse for a nuclear power industry, which the nation has resisted for decades.

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern spoke personally to her Australian counterpart, Scott Morrison, to tell him the vessels would not be welcome in the waters of her country, which has been a no-nuclear zone since 1984.

Six countries — the UK, US, China, Russia, India and France — already have nuclear-powered subs in their fleet, and many major developed economies, including the US and UK, use nuclear in their energy mix. In France, 70% of the country’s electricity is nuclear.

So what’s all the fuss about? Here’s why some Australians are bothered by this deal.

How is nuclear power made?

Nuclear power is the world’s second-largest contributor of low-carbon electricity after hydropower, according to the International Energy Agency. It accounts for around 10 percent of the world’s electricity, generated by just over 440 power reactors.

The power comes from a process known as nuclear fission, which involves the splitting of uranium atoms in a reactor that heats water to produce steam. This steam is used to spin turbines, which in turn produce electricity.

Uranium is a heavy metal found in rocks and seabeds, and it’s a powerful element. One pellet of enriched uranium — about the size of an eraser on the end of pencil — contains the same energy as a ton of coal or three barrels of oil, according to GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy.

While the process itself generates no emissions, greenhouse gases are generally emitted during the mining of uranium, and the enrichment process can be carbon intensive.

Is nuclear renewable?

The simple answer is “no.” The energy produced by nuclear power plants is in itself renewable, and the steam produced in nuclear reactors can be recycled and turned back into water to be used again in the nuclear fission process.

The materials used in its production, however, are not renewable — the metal is technically finite. But there is an argument that it can be used sustainably; the uranium resources across the world are so large that energy experts don’t foresee it running out.

Many groups that oppose nuclear power, however, do so because of the environmental destruction caused by uranium mining.

Governments in many parts of the world are relying on nuclear energy to help decarbonize their economies. It is widely regarded as an efficient way of producing electricity, and depending on the energy used to mine and enrich the uranium, it could potentially be a zero-emissions power source.

Beyond its low-carbon credentials, nuclear power is considered to have the highest capacity factor of any energy source, which means nuclear plants run at maximum power for more of the time than other types. In the US, they run at high capacity 92.5 percent of the time, government data shows. For coal, it’s around 40 percent, and wind is around 35 percent.

Nuclear power can prevent millions of tons of emissions from entering the atmosphere each year, compared to fossil fuels.

Sounds great. So why are so many Australians against it?

It’s not just Australia. Several countries have put the brakes on further development of the nuclear power industry since the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant lost power in an earthquake and tsunami, which meant the cooling systems failed, leading to nuclear meltdowns and hydrogen explosions, sending harmful radiation into the atmosphere. Parts of the city remain off limits.

It was the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986, when a test that went wrong triggered an explosion and fire, releasing devastating amounts of radioactive material into the air. Thirty-one people were killed in the accident itself, while many more died from the effects of radiation exposure in the following years, with some estimates in the tens of thousands.

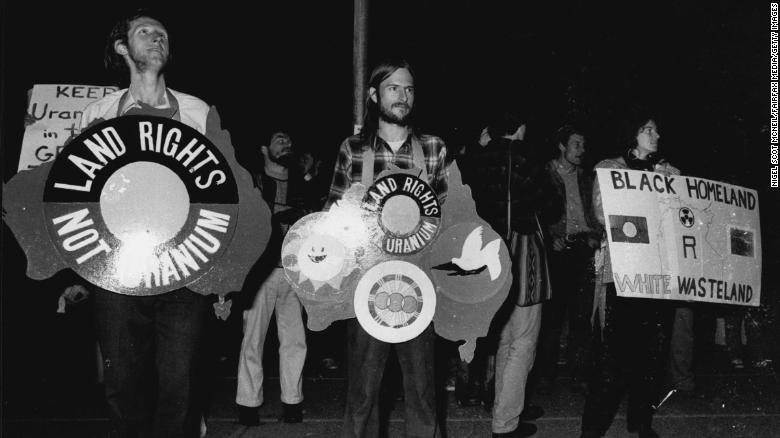

But Australia’s anti-nuclear movement goes further back than that, to a strong protest movement in the 1970s. This emerged largely because of concerns around the environmental impacts of mining uranium — which Australia has huge reserves of — but also due to worries around risks to public health, particularly among communities living near proposed facilities.

There are also concerns around how to safely store nuclear waste. Explosions or leaks of stored waste can impact human health too, though such disasters are far less common than they once were.

In 1977, the Movement Against Uranium Mining in Australia collected 250,000 signatures for a moratorium on extracting the metal, even though nuclear power wasn’t being used in the country. But Australia still mines the metal today and exports it to generate nuclear power in other parts of the world.

There is growing political pressure in Australia coming from leaders of the Liberals — which is Australia’s conservative party — to start using nuclear power. Without it, some argue, reaching net zero by 2030 will be impossible. It has resisted nuclear largely because it has had plentiful coal and gas reserves, but Australia is under pressure to wind down its use of fossil fuels.

When announcing the new deal, Morrison said Australia was not seeking to develop “civil nuclear capability,” which would include nuclear power plants. But Greens Party leader Adam Bandt criticized the agreement in a tweet as putting “floating Chernobyls in the heart of Australia’s cities,” saying it “makes Australia less safe.”

Bob Brown, a former Greens leader who campaigned against nuclear warships coming into Tasmania in the 1980s, told the Australian Financial Review on Thursday the deal put the country closer to developing a nuclear energy industry and warned of a backlash.

“I think it’s very cowardly what the government’s done,” Brown said.

“It’s made a decision without reference to the public, knowing the public would oppose it.”

And what’s New Zealand’s stance?

New Zealand is one of the few developed countries that does not have any nuclear reactors whatsoever. It also has a zero-nuclear zone which prevents nuclear weapons or nuclear ships from entering into its territory.

In September 1978, the New Zealand government released a Royal Commission of inquiry into nuclear power, and a decision was made for the country to use its own resources to produce electricity, rather than implementing nuclear plants.

Hydroelectric energy — which harnesses energy from the movement of water — now provides 80 percent of the country’s power, and investing in nuclear plants is still not considered to be cost effective. The initial cost of building nuclear power facilities is extremely high, according to the World Nuclear Association.

However, the main reason for New Zealand’s opposition to nuclear power is — as in Australia — public opinion and concerns around safety and the disposal of nuclear waste.

New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance applies to nuclear power, nuclear-powered vessels, and nuclear weapons.

As reported by CNN