Local Jewish groups are working to funnel assistance coming from international Jewish organizations, but also dealing with increased requests for assistance from within

JTA — Nissim Pingle, the head of Mumbai’s Jewish community center, hasn’t left his home since March.

That’s when COVID-19 began to overtake India. A second wave of infections has overwhelmed its health system and is producing a daily death toll of at least 4,000. The country is on track to have the world’s highest death toll by far, as stories pile up of people succumbing to the disease because they cannot access oxygen or hospital beds.

India’s approximately 7,000 Jews, most of whom live in Mumbai, generally belong to the privileged minority with the means to self-isolate. But even within the community, India’s widely celebrated multigenerational households have increased anxiety about the virus’s onslaught.

Pingle’s parents live with him, his wife and their two young sons. So as cases began to rise, he closed up the family home as a bulwark against the pattern he saw playing out around him.

“Younger family members contract the virus, sometimes without symptoms, and transmit it to the elderly people in the household, who are much more vulnerable,” he said.

Now Pingle, 41, is working to turn the JCC he runs, which usually hosts community events, into the base of operations for the aid effort to India by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which assists with disaster relief worldwide. The JDC, which funds the JCC’s work, is having three ventilators, each costing about $10,000, shipped from Israel to Indian hospitals, according to Pingle.

It’s part of a global effort by Jews in India and beyond to combat what is quickly emerging as a humanitarian crisis of unprecedented proportions. The majority of Indians live on less than $3.10 a day, according to the World Bank, and the absence of basic sanitary conditions in some places, the prevalence of multigenerational households and a lockdown preventing many wage earners from working mean that many Indians are in deep need, even if they and their families survive COVID-19.

“We are Indians first,” said Yael Jirhad, an occupational consultant from Mumbai. “It is heartbreaking.”

Jirhad’s husband, Ralphy, is part of a Rotary Club effort in which members transport food and other essentials to needy residents of the city.

The Mumbai Chabad House, run by Rabbi Israel Kozlovsky and his wife, Chaya, is raising money with donors from around the world who have funded Jewish outreach in the city to deliver food and other essential items to non-Jews living there and in nearby villages, where families largely depend on salaries earned in the city but now on hold due to the lockdown.

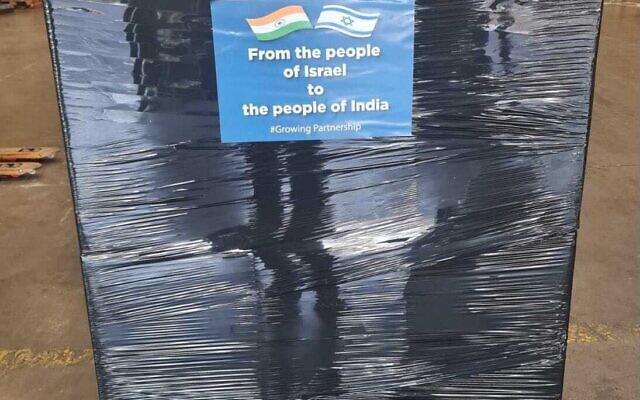

Israel’s Foreign Ministry has begun dispatching thousands of oxygen generators to India, among other medical gear items. And ISRAid, an Israeli nonprofit, is also helping in the most affected areas with support from the American Jewish Committee.

On Thursday, UJA Federation-New York, the largest Jewish federation in the United States, announced that it would send $200,000 in relief funds to India.

The contributions represent a drop in the bucket of what’s needed: India is reaching new highs in cases and deaths daily, while its vaccination campaign has slowed. Grim pictures of mass cremations have become impossible to miss in global news coverage. The United States has cut off travel from the country.

While the Jewish community has fared better than many others, there are signs that the crisis is also having an effect on Indian Jews.

The number of people from the Jewish community who asked the JDC for financial support or material aid increased by about 35% over 2019, according to a JDC official. About 160 community members are currently receiving support.

Chabad is seeing a similar increase in requests for help by Jews, Kozlovsky said.

For many Indian Jews, the effects have been more psychological.

Jewish community life in Mumbai has ground to a halt since March. The city has seven active synagogues and three Jewish schools, although two of those have more non-Jewish students than Jewish ones. Mumbai also has a Jewish nursing home, Pingle’s Evelyn Peters JCC and several Jewish cemeteries.

The Jirhads, whose two sons are living abroad, are the only residents of their home in Mumbai, where the average household has five members. Living away from their children and other relatives is at times difficult, Yael said, especially in a society where family is all important.

But during the pandemic it has allowed the Jirhads to volunteer where help is most wanted without fearing that they would thus infect others in their household.

The family of Herzel Simon, a member of the congregation of the Chabad-affiliated synagogue in Mumbai, has been particularly careful not to contract the virus because they live with his father, who had a medical procedure in January, making him especially susceptible to complications of the disease.

But Simon, 46, nonetheless caught the local variant of the bug, which scientists say is especially contagious. Simon displayed no symptoms, and the infection was discovered only after a blood test showed he had antibodies. His father has not displayed symptoms, but Simon said the experience made him worry about his father’s health.

Staying home, even with the knowledge that a crisis rages around them, has had some silver linings for Pingle and his family. His elder son, 12-year-old Aviv, has more time to study for his bar mitzvah with Pingle’s 73-year-old father, Shaul, who for many years served as cantor at his local synagogue.

“Like most Indian Jews, we are certainly better protected than the general population in India. But for my parents, isolation has been difficult because they really don’t go out of the house much at all,” Pingle said.

“Yet it has made us even closer than before. And if we feel like we need to go to synagogue, we can always visit my father’s room. He has so many books there it looks like a shul.”

As reported by The Times of Israel