Friday, September 4 was one of the happiest days in recent memory for Mayila Yakufu and her family.

That day, Yakufu, a 43-year-old ethnic Uyghur, had been freed from a Chinese detention camp and allowed to return home to her three teenage children and aunt and uncle in Xinjiang, western China. It was the first time she’d seen her family in nearly 16 months.

The same night, Yakufu was even able to video call her cousin, Nyrola Elima, who lives in Sweden.

“I didn’t recognize her at the very beginning, because she looked so pale.

She looked so weak and she had short hair,” Elima said. “She was terrified, she didn’t dare to speak too much with me.”

Elima quickly passed on the news to Yakufu’s parents and sister who live in Australia.

“I can’t describe my feelings, how happy I was when I heard my sister had been released,” said Marhaba Yakub Salay, Yakufu’s sister. “At the time, I still remember my heart was going to explode.”

Yakufu had spent more than a year in Yining Detention Center — her second stint in Xinjiang’s shadowy network of internment camps. Before that, she’d been held in a different camp for 10 months. Yakufu’s apparent crime was transferring savings to her parents in Australia, to help them buy a house.

The US State Department estimates that since 2017, up to two million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other ethnic minorities could have passed through the camp system, which China calls vocational training centers designed to fight extremism. Leaked documents seen by CNN show the extent of the mass surveillance apparatus that China uses to monitor Uyghurs, who could be sent to a camp for perceived infractions such as wearing a long beard or headscarf, or owning a passport.

For the family, having Yakufu back home was all that mattered. But her freedom was shortlived.

A day later, Chinese authorities took her away again, this time to Yining People’s Hospital in western Xinjiang, her family said.

They said the authorities didn’t give them a medical reason for her admission to hospital, but they did pass a message to her aunt and uncle: stop your daughter, Nyrola, from tweeting.

“I told the entire world”

For months, Nyrola Elima had been campaigning to secure her cousin’s release from her home in Sweden, more than 3,000 miles (4,900 kilometers) away from Xinjiang, by lobbying parliamentarians, speaking with NGOs, and tweeting.

Elima left Xinjiang nearly a decade ago to study and to get a better job.

She now works as a data analyst and has a Swedish passport and husband.

She says that since she began speaking publicly — she gave her first print interview to the Washington Post in September 2019 — the Chinese authorities have been tracking her closely; in Xinjiang, police officers have approached her parents about her activities multiple times. But she says she feels she had “no options left” other than to speak out, as silence didn’t help her family.

After the short video call with her cousin, Elima posted a Twitter thread about her release, saying she was “overwhelmed” with relief, but worried because she felt her cousin was “not fully free.”

Update dear friends: I’m so overwhelmed now, please forgive me if I could not express myself properly. Today, September 04, 2020, I got a message from my mom that after 2 years and 3 months of arbitrary detention, the Chinese government just released my cousin, Mahire Yakub

— Nyrola (@nyrola) September 4, 2020

“I put it on Twitter, I told the entire world,” Elima says. “They took her immediately to the hospital. This is the way they want me to stop, they want to censor me.”

Elima’s mother in Xinjiang asked her to stop tweeting about the case.

But after Yakufu was taken to hospital, the family didn’t hear anything about her for weeks, and no visits or phone calls were allowed. Elima became increasingly anxious.

On September 19, she tweeted again about her cousin’s mysterious detention in hospital, posting: “I put up with it for fourteen days, kept my mouth shut for fourteen days, listened to my parents educate me for fourteen days, and tried to persuade my sister as a peacemaker for fourteen days.

In those fourteen days, my sister’s children cried at me, begging me to stop speaking up, twice. So if you have something to say, just come directly to me, I’m willing to talk to you. Just stop pushing my parents and the children. My parents are really going to be sick, and the kids are really going to have a breakdown.”

Within 30 minutes, Elima said police officers arrived at her mother’s house in Xinjiang with printed copies of the tweets. Again, they demanded that they stop their daughter from speaking out.

“(They) said, Look, your daughter is talking about the Chinese Communist Party,” Elima said. “‘She’s making (the) Chinese government look very, very bad. You need to tell your daughter, stop it.'”

Rian Thum, a Uyghur historian at the University of Nottingham in the UK, said it was the first time he’s heard of police directly confronting family members with social media posts by Uyghurs abroad. “It shows that the Chinese authorities are very concerned about international opinion, that they’re monitoring Twitter, which is of course banned in China,” he said.

Elima says the Chinese authorities confronted her family about her tweets three times. The first time was in August, when Elima reposted a Chinese state media article: she was highlighting that the piece used a picture of her mother apparently happily celebrating International Women’s Day in March — in reality, during that period her cousin was in her first detention camp in 2018.

“It is propaganda,” Elima said. If her happiness, and that other Uyghurs portrayed in state media, is real, “then why (are) there so many Uyghurs outside looking for their family members?” she asked. “Open the region.

Let everyone travel there freely or let the Uyghur people go abroad.”

Elima’s social media is not the only thing under surveillance. In 2017, she says Chinese authorities demanded a photograph of her Swedish passport, and her Swedish address, via her mother over WeChat. She provided the details and moved house straight after.

“I am terrified every day,” Elima said.

“What we see in this case is intimidation by the Chinese police through family members (to) other family members abroad,” said Thum. “It’s also a case that shows how the Chinese government thinks about Uyghurs as threats, and how they think about international connections.”

Faced with the increasing threats to her family, Elima has again decided to speak publicly, giving her first interview on-camera to CNN. “I feel there’s a gun behind my head, and I feel that I’m playing Russian (roulette) with the Chinese government,” Elima said. “Every time when I move, I may well face very serious consequences, and my family members will pay for that.”

Many Uyghurs abroad are faced with the same gut-wrenching decision: do as instructed and stay silent, or risk speaking out to try to offer some protection to relatives, in the hope that if their names become well-known it will be more conspicuous if they disappear.

A day after Elima’s interview with CNN in December, the family got more bad news.

They were told via a phone call from the authorities that Mayila Yakufu had been taken from the hospital to the detention center in late November.

Proving her innocence

Yakufu’s sister and parents live in Adelaide, South Australia.

Her sister, Marhaba Yakub Salay, 32, said Yakufu had been a model citizen in Xinjiang, working multiple jobs as a successful insurance saleswoman and a Mandarin teacher. She is fluent in Chinese and Uyghur and understands English.

“She worked really hard, because she’s (a) single mother of three,” Salay said. The children’s father had left when they were very young, “so she knows she has to be very strong.”

The Chinese government says the “vocational training centers” in Xinjiang are part of a “poverty alleviation” scheme to help train poor rural workers to learn Chinese and find employment. In a Xinjiang government press conference in Urumqi on November 27, videos were shown of seven Uyghurs who had “graduated” from the camps. They all praised the system, saying it had helped them to turn away from extremism and find good jobs.

“I’m now a workshop manager in a garment factory in Hotan County,” said Tusongnisha Aili, a woman in one of the videos. “I received a good education at the training center. I learned fashion design, sewing techniques related to making clothing.”

But multiple Uyghurs who have spoken to CNN after they left the camp system have dismissed these claims from officials. They say many of the people taken to the camps already spoke fluent Chinese, had a good education and salary, or weren’t even living in China at the time.

The first time Yakufu was taken into a camp, on March 2, 2018, she was not accused of any specific offense. But the second time she was detained, in April 2019, she was accused of “financing terrorist activities” — a charge experts say has been leveled against multiple Uyghurs who sent money outside of China. She also had a sum of nearly 500,000 RMB ($76,000) confiscated by the authorities, and her aunt and uncle were put under house arrest, the family says.

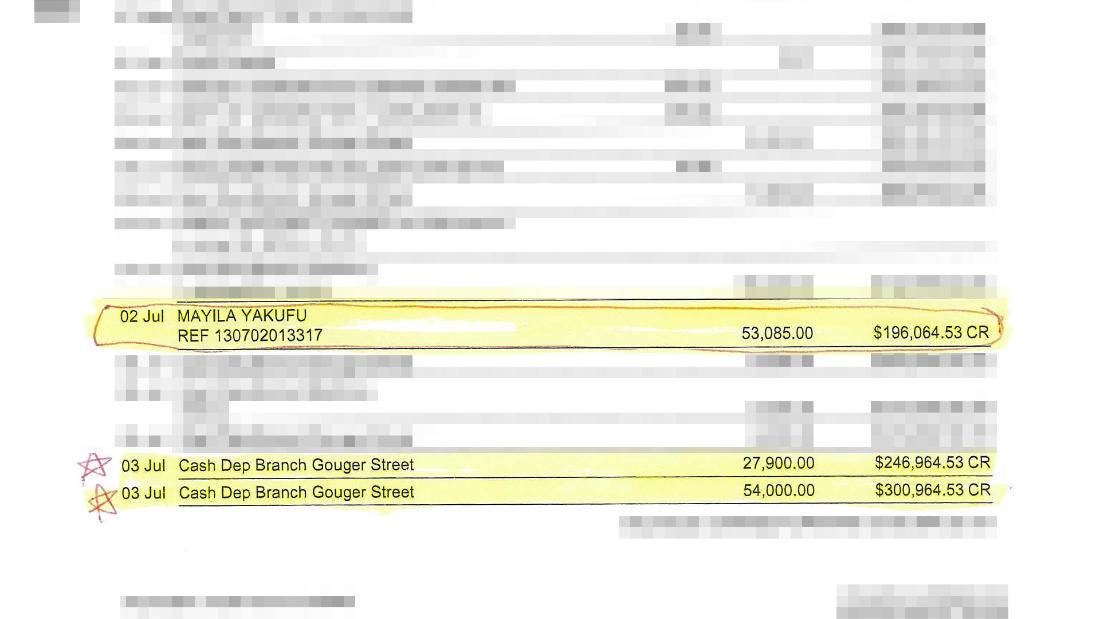

In July 2013, Mayila Yakufu and her aunt and uncle sent nearly $135,000 Australian dollars ($100,000) to the family in Australia to buy a house, in three separate transfers from the Bank of China to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

To prove Yakufu’s innocence, the family has meticulously documented the bank transfers and house purchase records and sent the evidence to the Australian and Chinese governments.

Australian Federal Police have confirmed to the family in writing that they are not under criminal investigation in Australia, although they would not comment on the case to CNN.

“It really shows you the extent that the Chinese government will go to, and the very innocuous activities that can result in imprisonment,” Rian Thum said.

When asked about Yakufu’s case, the Chinese Mission to the EU told CNN that her family were believed to be members of the “Eastern Turkistan Liberation Organization,” which the Chinese government labels a terrorist organization.

A spokesperson said Yakufu had been informed in writing that financial transactions with her family would be illegal. “In spite of that, she still provided funds to them. By so doing, she was suspected of violating article 120 of China’s Criminal Law for abetting terrorist activities,” the spokesperson added. “She was arrested by the public security authority in May 2019 and the case is currently under trial.”

In a statement, Yakufu’s family denied any links to terror groups and said the mission’s allegations were “demonstrably false.” If they had links to terror groups, Chinese authorities wouldn’t have let them travel freely in and out of China in the years after the transaction was made in 2013, they said.

In July, the family asked Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs (DFAT) for help, and the department sent back the response they received from the Chinese Embassy in Canberra, which read: “Ms Yakefu Mayila was prosecuted in July 2019 for allegedly financing terrorist activities and is currently in good health.”

In an email to CNN, DFAT said it cannot comment on individual cases, but added that Australia has “serious concerns” about China’s treatment of the Uyghurs, and has “consistently urged China to cease the arbitrary detention” of Uyghurs and other Muslim groups in Xinjiang.

In the recent Xinjiang press conference, CNN asked for an official response to comments from US President-elect Joe Biden, who said that China’s policy against the Uyghurs amounted to “genocide.”

“As for the claim that Xinjiang is implementing a genocide policy, it is completely a false proposition and a vicious attack on Xinjiang by overseas anti-China forces,” said Elijan Anayit, the spokesperson of the Information Office of the People’s Government of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

“My daughter is suffering”

In Adelaide, Yakufu’s father, Yakefu Shabier, and mother, Bahaer Maimitiming, live with the burden of knowing the house they reside in may have caused their daughter to be imprisoned.

“I feel pain every day, as if I am stepping on nails, because the cost of this house is my daughter’s suffering,” said Shabier, 73. “My dream and hope is that my daughter be freed from oppression as soon as possible and reunited with us.”

The couple first came to Australia in 2007, to visit their son who had emigrated there several years earlier. After their son died in a drowning accident on New Year’s Eve in 2008, they decided to stay in Australia permanently. Their daughter, Marhaba Yakub Salay, then moved there in 2011. But Yakufu, who had children, chose to stay in Xinjiang.

The family now runs a Uyghur restaurant in central Adelaide called Tangritah.

“Ever since we came to Australia, we worked extremely hard, we opened a restaurant, and we are trying our best to be good citizens and contribute to Australia,” said Maimitiming, 64. “We are not terrorists.”

Salay said working is the only way her parents know how to deal with the pain caused by her sister’s detention. “They want to rescue their daughter, but can’t do much here,” Salay said. “They don’t know what to do. So, they just push themselves to work hard.”

The family’s goal is to keep the pressure on the Chinese government by highlighting what is going on in Xinjiang.

“What happened to my family, it’s also happening to other Uyghur families,” Elima said. “Our family’s case is just (the tip of the) iceberg.”

“It’s very difficult to know whether their loved ones are still alive in some cases, or whether they’re interned in these camps, some of which have really horrific conditions,” Rian Thum said. “So there’s a major wave of depression and trauma that Uyghurs outside of China are suffering.”

“China threatens Uyghurs overseas, and it works,” Salay said. “China uses my sister as a hostage strategy.”

This strategy is one which kept their own family quiet for a long time, she adds. “Many Uyghurs censor themselves,” Salay said. “We were one of them.”

Now Yakufu is back in detention, Salay only hopes they can try to keep her from harm. “The situation gets worse and worse when I keep silent,” Salay said. “Now I have no choice. If I don’t speak up, she (might) end up in one of the dark corners in the prison.”

Going public is not a decision that comes lightly for the family. Elima is battling what she calls “survivor’s guilt.” At night she lies awake in her “comfortable bed” and worries about the kind of conditions her cousin is sleeping in.

She remembers the last snatched conversation she had with her cousin in September.

That day, Yakufu had told her: “Please tell my parents I miss them so much … I dream about them every night.

“That is the only one way I can meet my parents, my children, my sister, your parents and you.”

As reported by CNN