Long-term care facilities have been hardest hit by COVID-19, leaving the children of patients scrambling to help them when they can’t be physically present

WASHINGTON — Pearl McLane had just gotten out of the hospital. It was February 2020, and she had endured an eight-month stay at Shady Grove Medical Center in Rockville, Maryland, recovering from a CRE superbug that nearly took her life.

But the 87-year-old was still in a fragile state. Beset with medical ailments, including vascular dementia, blindness in one eye and hypertension (she had previously had a quadruple bypass surgery), McLane’s doctors did not give her a positive prognosis.

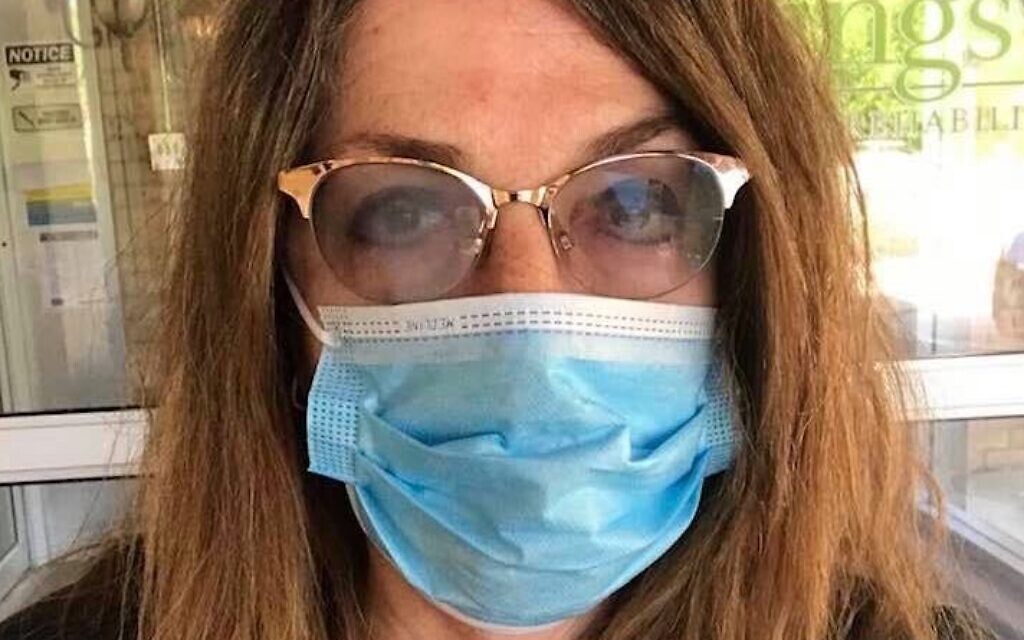

So her daughter, Debra Schackner, made the agonizing decision to place McLane into the Jewish Social Service Agency’s hospice care.

But that decision came with more problems. She kept falling down, and the agency determined that she was such a fall risk that she could no longer stay at the home without 24/7 care, which Schackner quickly realized she could not afford.

Instead, Schackner moved her mother into one of the few nursing homes in the state that has a dementia unit: Collingswood Rehabilitation and Healthcare Center in Rockville, just a few minutes from her residence.

Little did she know back in February, however, that a global pandemic was about to reach America’s shores — and lead to outbreaks in nursing homes all across the country, where thousands of at-risk elderly patients are living in confined spaces susceptible to contagion.

“We already knew there was COVID-19 in China,” Schackner told The Times of Israel. “We didn’t know that it was a problem in the US yet.”

Throughout the rest of February and the beginning of March, Schackner could visit her mother after nurses took her temperature and after she signed a form verifying that she had not recently visited China.

Then, on March 11, Schackner went to visit her mother one night and was told by an administrator that she wouldn’t be able go inside the facility anymore.

To protect the patients from the novel coronavirus, Collingswood was restricting all visitors, including close family members, except in near-end-of-life situations.

The new policy would go into effect the next day.

“My whole life changed after that,” said Schackner, a former federal government TV producer. “I haven’t seen my mother since and every day has been a new nightmare. I can’t check in on her. I can’t see how she’s doing up close. I can’t be there to make sure she’s getting the care that she needs. People in nursing homes are more in danger of COVID than anyone else in the country.”

As of last week, roughly one in five of the reported coronavirus deaths in the United States were of people living in or connected to nursing homes, according to the Wall Street Journal, many of which have struggled over the last two months to acquire personal protective equipment (PPE).

The problem has been especially acute in Maryland, where roughly half of all COVID-19 deaths have come from nursing homes.

Collingswood is no exception. As of this writing, the facility has had 29 staff infections and 1 staff death, and 91 resident cases and 23 resident deaths, according to the most recent data from the Maryland Board of Health.

Schackner spends each day in dread as her mother remains inside a facility where the virus is spreading rapidly. If her mother were to get infected, Schackner said, she would have little-to-no chance of survival, given her fragile condition.

Schackner already knows that McLane has been in close proximity to the virus. Last week, she said she was notified by Collingswood’s staff that her mother’s roommate tested positive for COVID-19 and was moved into another ward.

Relying on FaceTime to stay connected

Without the ability to enter the nursing home, Schackner has relied on technology to remain apprised of her mother’s condition. Mainly, the two of them FaceTime each day. The facility’s dementia unit, much to her chagrin, does not have windows, where she could see her mother up close.

“Without FaceTime, you can’t see your mother or a loved one,” she said.

But the more they communicate, the more Schackner becomes worried about the care that her mother is receiving.

“She has food delivered at five at night, but if I call her at eight, the food hasn’t been touched,” she said. “Nobody is there to assist her. She can’t even open the tray with her arthritic hands.”

One night last week, Schackner called this reporter from her home phone while she was FaceTiming with her mother, who was in a delirious state and calling for help. No one was coming to her aid.

“I feel like I’ve been kidnapped,” McLane bellowed. “I don’t know what to do. Someone should rescue me.”

Schackner said she had called the front desk 10 minutes earlier to tell them her mother had been hallucinating — McLane thought she was inside an old friend’s apartment — and needed a nurse.

“There’s not enough help — ever,” Schackner said.

Eventually, a nurse did arrive, and attributed the outburst to McLane’s dementia, Schackner said.

The daughter followed up by emailing a doctor on staff, saying she wanted her mother to have constant supervision.

According to Schackner, the doctor replied by telling her that Collingswood had 24 patients in the unit and only a few nurses on duty at a time, thereby making constant supervision impossible.

Schackner, an only child whose father died in 1995, claimed that she often has trouble getting in touch with the staff on duty.

“Every day it takes me an hour and a half to get someone on the phone,” she said. “There’s no one reporting to you your mother’s record of care. You don’t know whether she showered or not.”

Doing the best they can?

A Collingswood representative stated that the dementia unit keeps two nurses, one medical technician, and four certified nursing assistants on staff during the day and one nurse and two certified nursing assistants overnight, per the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines.

“We recognize this is an incredibly stressful time for anyone with an elderly or infirm loved one, particularly in a group setting,” said Sandy Crisafulli, a spokesperson for the nursing home. “The care of these loved ones is our sole focus.”

She said that Collingwood has set up a “phone line explicitly for families with questions, and we have a team in place that responds as quickly as possible to those calls.”

She also noted that Collingswood has contracted with third-party staffing agencies to bring in additional nursing staff when needed, as nursing homes nationwide have suffered from staffing shortages induced by COVID-19.

“The family member in question also has the personal cellphone numbers of our director of nursing, facility administrator, and multiple support personnel,” Crisafulli told The Times of Israel. “She has had multiple, in-depth conversations with care team members, and our team facilitates FaceTime visits for her and her mother nearly every day.”

Virtual moments of connection

Schackner said that those virtual meetings are the only way for her to let her mother know that she is there for her, even if she can’t be with her physically.

“There are some moments, every once in a while, when I do get her on FaceTime and she feels connected,” Schackner said. “She sees my dog. She smiles. I feel a sense of momentary relief. I know that I’m doing all that I can do. But my concern is, when does it end?”

Disconcertingly, Schackner said there’s no sense that the conditions in nursing homes preventing her from being able to visit will change any time soon — and she can’t afford to have her mother live with her and receive the around-the-clock care she needs.

While states all across America partially reopened this weekend, there is no timetable for when long-term care facilities can allow visitors to come back, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention maintain that people over the age of 65 are most vulnerable to experiencing fatal complications from the virus.

“With nursing homes, there’s nobody saying we can ever see our parents in person or go back to normal,” Schackner said. “Most likely, my mother will die before I ever see her again.”

As reported by The Times of Israel