As 40-year head of the Jewish United Fund, Steve Nasatir helped bring in $8 billion from the city’s 300,000 Jews

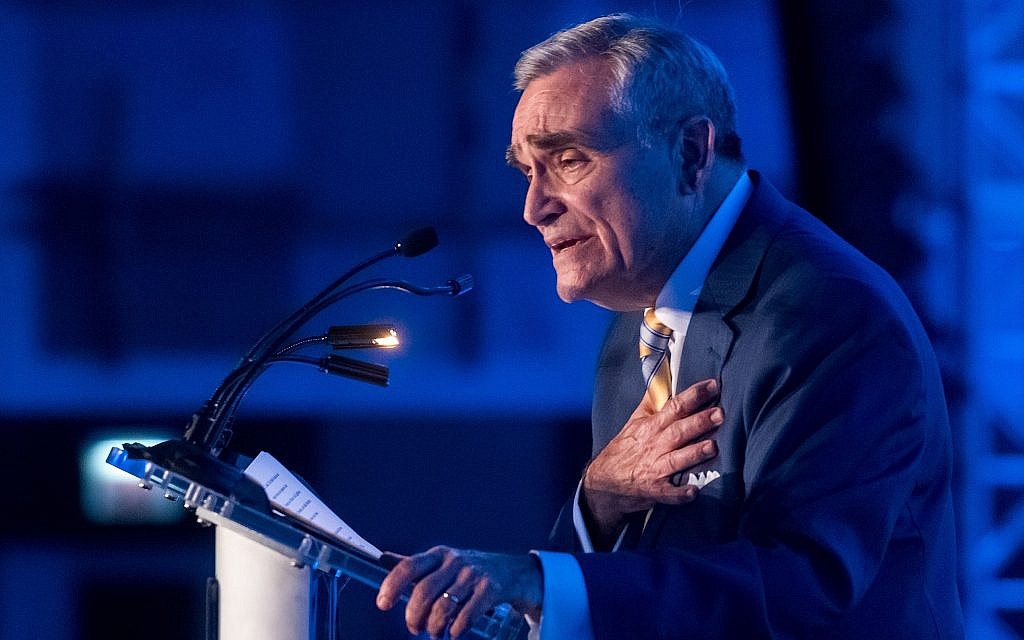

JTA — Before he stepped down last week, Steve Nasatir led the Chicago Jewish federation for four decades. In that time he built an empire.

His federation, called the Jewish United Fund, or JUF, does the things that most Jewish federations do: It raises money for an array of Jewish causes across the city, country and world, with the donations going to a central fund and allocated as its leaders see fit. Those causes include Israel, Jewish day schools (19, in fact) and fighting poverty.

It also acts as an address for Jewish programming and setting policy agenda.

But JUF is much more powerful than most federations: It controls the Hillels on all the campuses in Illinois and owns the real estate that houses various Jewish institutions in the Chicago area, from community centers to social service agencies. And JUF provided the loan guarantees to the city’s Jewish day schools that enabled them to build their buildings.

It’s a federation that raises lots of money. In Fiscal Year 2018, JUF’s general fundraising campaign brought in nearly $87 million from a community of approximately 300,000 Jews. By comparison, the federations serving San Francisco and Washington, D.C. — communities similar in size — each brought in less than $20 million in unrestricted and designated fundraising.

In the 40 years with Nasatir at the helm, according to JUF, the federation brought in $8 billion through all of its fundraising methods.

“$8 billion, that’s kind of a lot,” Nasatir, 74, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in a recent interview. “Really being involved in everything from [fighting] BDS to helping Holocaust survivors to taking care of the poor to building day schools to being engaged in Israel both philanthropically and in an advocacy way, to participating in [combating] the hunger in the Soviet Union and on and on and on, I think makes for greater and greater success because the community recognizes that that one place is JUF federation.”

He began working at JUF in 1971 and assumed the leadership in 1979. Nasatir has been succeeded by his son Lonnie, formerly the Midwest director of the Anti-Defamation League who took over this week. Nasatir will stay connected to JUF as executive vice chairman. According to Haaretz, as of 2015 he was one of the highest-paid federation executives in the country.

Nasatir spoke of the “very, very big table” that JUF sets for the array of Jews and Jewish groups in Chicago, but he made clear it was JUF that would decide who gets to sit at the table. The power of the purse and the federation’s influence over Chicago Jewish institutions meant that JUF can effectively decide which groups and views are funded in the Jewish community there and which are in and out of the communal umbrella.

(JUF has contributed to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and its parent company, 70 Faces Media, through donations and subscriptions to its syndication service.)

“There’s no question we’re a top-down community in many, many ways,” he said. “We recognize the bottom-up and the diversity, but yes, there are rules.”

Later he added, “We do have guidelines. If you want to be part of the federation system, there are the kinds of things that you can do, there are the kinds of things that you can’t do. It’s not ad hoc.”

JUF operates with many of the same policies as other federations. Its boundaries on Israel discourse, for example, fall within the norms of federations nationwide. It opposes the boycott Israel movement, and also won’t direct donor money to causes on the right that advocate violence toward or forcible expulsion of Israeli Arabs.

What sets JUF apart is its reach. In one instance, in 2012, JUF mandated budget cuts to the University of Chicago Hillel. In response, the Hillel board and its director, Dan Libenson, threatened to separate from JUF. So JUF fired the director and board with no notice and ordered them to vacate the building immediately.

A group of University of Chicago professors who objected to the firing called it “disgraceful and unwelcome in our community.” Nasatir wrote in a letter to students about the firing that “our hand was forced” and JUF tried “to avoid the separation with Dan and the advisory committee, which we neither desired nor initiated.”

A millennial Jew in Chicago who is connected to JUF said it’s hard to dissent from federation and still be able to participate in the local Jewish community. Fearing a backlach from JUF, this person asked to remain anonymous.

“Being on the wrong side of federation doesn’t just hurt your standing within the federation, but can have an impact on your standing within the entire Chicagoland Jewish world,” the millennial said. “Its ability to support all different sorts of causes, including very, very innovative ones, gives federation the ability to set restrictions on groups that probably would have no connection to federation in other cities.”

Nasatir and his supporters say the federation’s size allows for a more effective and efficient system, and point to his achievements over the decades. In particular, Nasatir mentioned the 30,000 Soviet Jews whom JUF resettled in Chicago, and its work helping Israel, along with anti-poverty activism it led locally.

During the late 1980s and early ’90s, JUF raised a total of more than $100 million for Soviet Jewish resettlement, Nasatir said. In 2004, while Israel was fighting the second intifada, JUF raised more money for Israel per capita than any other Jewish federation.

“We’re very connected to the notion of collectiveness, and we’re able to project the story of connecting the members of this community — and that includes the donors to this organization — to the great events of Jewish life,” Nasatir said. “The ultimate referendum is that annual campaign. If we really had it wrong, we wouldn’t see the continued expansion of an annual campaign year after year after year.”

Part of that success stems from the personal attention that Nasatir paid to fundraising, said Misha Galperin, a former Jewish Agency for Israel executive who considers Nasatir a mentor. Galperin said that Nasatir would personally meet with 200 donors every year.

“The number of people he individually met with every year and solicited was stunning,” said Galperin, now the president of Zandafi Philanthropy Advisors. “I tried to emulate him and I never reached his numbers. He backed up his commitment and his faith and his theory with delivering results.”

JUF has also retained its power by being able to cultivate large donors while simultaneously doing a good job of leveraging donor-advised funds, said Lila Corwin-Berman, a history professor at Temple University and author of the forthcoming book “The American Jewish Philanthropic Complex.” Donor-advised funds allow donors to park money in an account at federation and then donate that money to causes of their choosing.

“During the time of his leadership, a lot of federations have struggled and private foundations have become a lot more powerful,” she said. “I think Chicago has done pretty well, and it’s in particular because he’s done a good job of treating it more like a private foundation than a federation.”

JUF’s reach helps draw young adults to a continuum of programs, said Rabbi Megan GoldMarche of the Silverstein Base Hillel, which serves college students and post-college young people and is under JUF’s umbrella. Affiliations with Hillel and JUF can make it harder to attract some young Jews, GoldMarche said, but others end up coming to Base Hillel after attending JUF social programs.

“A big piece of it is having access to reach a wide range of people we wouldn’t otherwise reach,” she said. “There’s a whole range of people who don’t know that they’re looking for Jewish learning, who don’t realize that what they need in their 20s is a rabbi, and often those people first come through our doors through a co-sponsored program with federation.”

JUF is looking now toward its next generation, too. Nasatir said he had “zero” involvement in the process that led a search committee to appoint his son as his successor. He called the question a “sore spot,” but said he was “very proud.”

“It was not my decision so I have nothing to say,” he said. “It’s obvious, it is. My son succeeded me. OK. Judge my son by what he does and judge me by what I do.”

In May, JUF thanked its longtime chief executive at a gala whose guests included Chicago’s newly elected mayor, Lori Lightfoot, and the former General Dynamics chair and megadonor Lester Crown.

“The federation over the years has become a place where different segments of the community, Orthodox and secular and a whole range of things can come to the table and discuss things,” Nasatir said. “They can still talk together and work together for what they see as the larger good.”

As reported by The Times of Israel