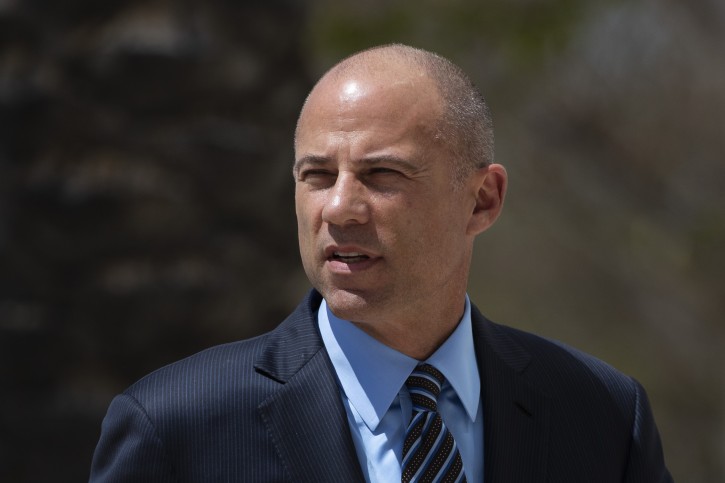

Los Angels – Attorney Michael Avenatti has been charged in a 36-count federal indictment alleging he stole millions of dollars from clients, did not pay his taxes, committed bank fraud and lied in bankruptcy proceedings.

Avenatti, 48, was indicted late Wednesday by a Southern California grand jury on a raft of additional charges following his arrest last month in New York on two related counts and for allegedly trying to shake down Nike for up to $25 million.

The attorney best known for representing a woman in lawsuits against President Donald Trump said on Twitter Thursday that he will plead not guilty to the California charges.

“I look forward to the entire truth being known as opposed to a one-sided version meant to sideline me,” he wrote.

The new charges do not include the New York extortion case alleging Avenatti demanded millions to stay quiet about claims he planned to reveal about Nike paying high school players. Avenatti has said he expects to be cleared in that case.

The 61-page Southern California indictment alleges Avenatti embezzled from a paraplegic man and four other clients and deceived them by shuffling money between accounts to pay off small portions of what they were due to lull them into thinking they were getting paid.

Avenatti, 48, is also charged with not paying personal income taxes, not paying taxes for his various businesses, including two law firms, and pocketing payroll taxes from the Tully’s Coffee chain that he owned, the indictment said.

Between September 2015 and January 2018, Global Baristas US, the company that operated Tully’s, failed to pay the Internal Revenue Service $3.2 million in payroll taxes, including nearly $2.4 million withheld from employees, the indictment said.

When the IRS put tax levies on coffee company bank accounts to collect more than $5 million, Avenatti had Tully’s employees deposit cash receipts in a little-known account, the indictment said.

Avenatti was also charged with submitting fraudulent tax returns to get more than $4 million in loans from The Peoples Bank in Biloxi, Mississippi, in 2014. The tax returns he presented to the bank were never filed to the IRS, prosecutors have said.

The charges are the latest major blow to a career that took off last year when Avenatti represented Daniels in her lawsuit to break a confidentiality agreement with Trump to stay mum about an affair they allegedly had.

Avenatti became one of Trump’s leading adversaries, attacking him on cable news programs and Twitter. At one point, Avenatti even considered challenging Trump in 2020.

But back home, his business practices had come under scrutiny from the IRS and a former law partner who was owed $14 million by Avenatti and the Eagan Avenatti firm, which filed for bankruptcy.

The indictment said Avenatti made false statements in bankruptcy proceedings by submitting forms under penalty of perjury that under reported income his firm received.

The most glaring example of deception and fraud was described in the indictment as scheming Avenatti allegedly did to deprive clients of money they were due from legal settlements or sales of stock and the actions he took to cover his tracks.

In a case involving one client, Avenatti allegedly funneled a $2.75 million settlement into his bank accounts and spent $2.5 million on a private airplane, the indictment said.

Although Avenatti was due a portion of settlement funds for his work, the charges said he paid only a fraction of the money clients were due in some cases and strung them along while they waited to be paid.

Avenatti allegedly drained a $4 million settlement he negotiated in 2015 on behalf of Geoffrey Johnson, who was paralyzed after trying to kill himself in the Los Angeles County jail, the indictment said. Johnson was referred to as “Client 1” in the indictment, but was named at a recent court hearing involving the money Avenatti was ordered to pay his former partner.

Until last month, Avenatti had only provided $124,000 over 69 payments to Johnson, the indictment said.

Two years after the settlement was reached, Avenatti allegedly helped Johnson find a real estate agent to buy a house. But when Johnson was in escrow to purchase the property, Avenatti falsely said he had not received the settlement funds, the indictment said.

In November, when the U.S. Social Security Administration requested information to determine if Johnson should continue to receive disability benefits, Avenatti said he would respond, but didn’t because he knew it could lead to the discovery of his embezzlement, the indictment said. The failure to respond led to Johnson’s disability benefits being cut off in February.

After Avenatti was questioned about the alleged embezzlement during a judgment-debtor examination in federal court March 22, the indictment said he fabricated a defense for himself.

Avenatti had Johnson sign a document a day or two later saying he was satisfied with his representation, which the lawyer told him was necessary to get the settlement that had in fact been paid four years earlier, the indictment said.

When asked by The Associated Press last month about Johnson’s case, Avenatti said his client approved all transactions and accounting and had been kept in the loop.

“He has repeatedly thanked me for my dedication to his case and the ethics I have employed,” Avenatti wrote in an email response.

As reported by Vos Iz Neias