When a couple who survived the Holocaust first opened Hungarian Kosher Foods in 1973, the idea of having a certified grocery, bakery, and butcher under one roof was unheard of

CHICAGO (JTA) — America’s first all-kosher supermarket is set to change hands, marking the end of an era for Hungarian Kosher Foods, a Chicago-area landmark for 45 years.

Holocaust survivor Sandor Kirsche trademarked the slogan “All kosher, only kosher,” and since 1973 it has applied to the forward-looking kosher supermarket he founded, Hungarian Kosher Foods, under the supervision of the Chicago Rabbinical Council. Located first on Devon Avenue in this city and since 1986 in a 25,000-square-foot supermarket space in Skokie, Illinois, “Hungarian” revolutionized the way kosher cooks shopped.

“My father was always progressive,” said Ira Kirsche, Sandor’s son and Hungarian’s current owner. “We always talked about new things.”

In 1973, the idea of an all-kosher supermarket was virtually unheard of. Two markets — Shufersol in Israel and Seven Mile Market in Baltimore — offered an array of kosher items, but the idea of certifying an entire store kosher was new.

“It was a different world then,” said Lynn Kirsche Shapiro, Ira’s sister. Certified kosher foods were difficult to find, and many people didn’t bother, relying instead on reading package ingredients to see if they contained forbidden ingredients.

“Kosher consumers would go to a bakery, then a kosher meat market, then a kosher grocery store,” Lynn said. “Our concept was to bring it all together under one roof.”

On April 20, Orian Azulay, the owner of the kosher supermarket Sara’s Tent in Aventura, Florida, is set to buy Hungarian. It will be his first purchase since buying Sara’s Tent 10 years ago.

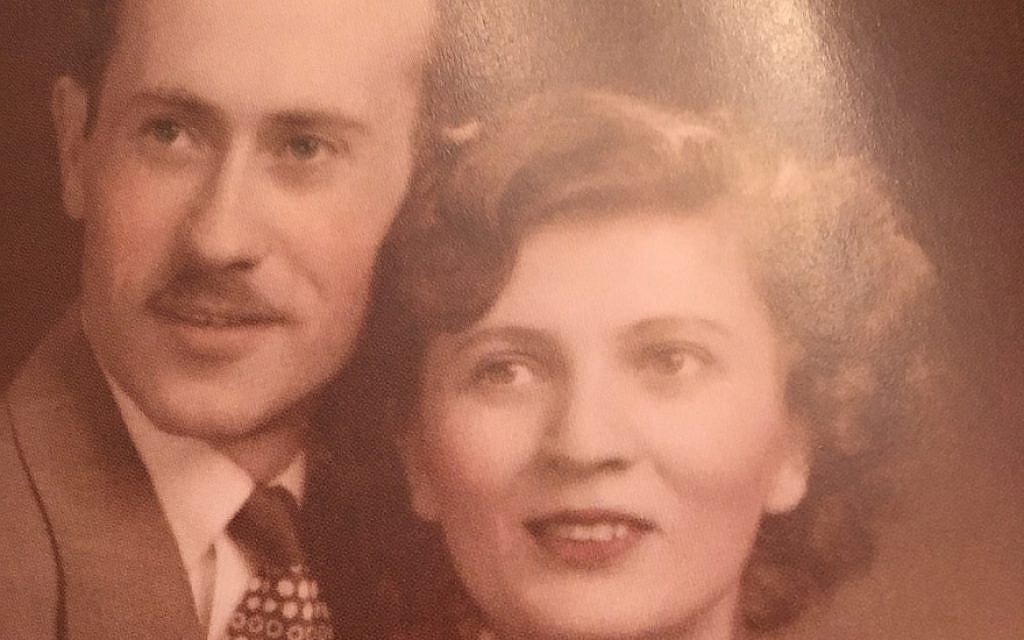

For Sandor Kirsche and his wife, Margit, keeping kosher was crucial, and kosher food was also a way of connecting with their families who perished in the Holocaust. Sandor and Margit grew up in Hasidic homes, Sandor in Czechoslovakia and Margit in Hungary. The rich fragrance of traditional foods like chicken soup and kreplach, paprikash with dumplings and homemade plum pie would fill the air on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

Each year, Sandor’s neighbors would gather at his home to bake the community’s matzah. They gathered for the last time in 1944, this time in secret: On the final day of Passover, the entire community was interned in a ghetto outside Uzhgorod, in what was then Czechoslovakia.

A month later, on the first night of the Shavuot holiday, Sandor was deported to Auschwitz along with his parents, grandmother, sisters, his little brother Chaim, aunts, uncles and cousins. Only Sandor survived; a tall man, at liberation he weighed a mere 70 pounds.

Margit’s family also was decimated in the Holocaust. Deported the day after Passover 1944, Margit survived both Auschwitz and the German labor camp Torgau. After the war, food became a way for Margit to explain the enormity of the tragedy that befell her family. One of her signature dishes is kippilach, or walnut crescent cookies — the pastries became a way to talk about Margit’s 12-year-old uncle Yitzchak Isaac, who was with her on the train to Auschwitz in 1944. He was so hungry, she recalled, that she gave him the few kippilach her grandmother had given her to eat.

Yitzchak Isaac was murdered on arrival. The story of the last cookies he ate ensures new generations don’t forget him.

“I knew I wasn’t going to die,” said Margit, who somehow managed to evade execution by working as a slave laborer first in Auschwitz, and then in Buchenwald and Torgau.

“These were my bedtime stories,” said Lynn Kirsche Shapiro of this and other family tales.

Sandor and Margit met in Germany after the war, married in 1947 and immigrated to the United States in 1948. They brought up their two children in the Humboldt Park neighborhood here. Although there were no relatives nearby, Margit and Sandor filled their apartment with the smells of cooking and stories about relatives who were no longer with them.

In their early years in America, Margit sewed clothes and Sandor worked various jobs until 1973, when they had scraped together enough money to buy a kosher meat market on Devon Avenue. They gradually turned it into a full-service meat market, bakery, deli and grocery.

From the beginning, Sandor and Margit made sure the store felt like home.

“My mother was the kitchen,” Lynn said, as many of the supermarket’s deli items hark back to treasured family recipes.

Even today, at 95, Margit, who lost her eyesight 20 years ago, still helps out with cooking. In March, she helped prepare for Hungarian’s last Passover at the Kirsche’s family store by helping make 120 pounds of charoset, the sweet holiday treat.

When Hungarian moved to Skokie, it finally was able to become what Sandor and Margit always dreamed of: a full-size supermarket with a bakery, meat, dairy and pareve (neither milk nor meat) deli items, and one of the country’s leading wine sections — all certified kosher. As kosher tastes changed, so has Hungarian, adding a health food section, imported items and even two dedicated sushi chefs over the years.

The store served as a meeting place and community resource. The Kirsches often donated food anonymously, including providing the weekly kiddush for a synagogue serving refugees from the Soviet Union for many years. One day Hungarian’s staff was startled when two customers called out to each other: They had been prisoners at the same Nazi concentration camp and had not seen each other in decades until the meeting in Hungarian.

The Kirsche family worked together, sometimes logging 24-hour work days. Lynn Kirsche Shapiro became a college math professor, but still worked at Hungarian during busy holiday periods.

Yet after 45 years, Hungarian found itself at a crossroads.

“I don’t have the next generation,” Ira said. His father died in 2007, and Ira’s wife, Judy, died six years later to the day.

“I’m here alone,” he said, noting that his staff is wonderfully supportive, but that Hungarian could not continue in its present form to a third generation.

Competition has intensified, too. In 2010, the Jewel supermarket chain opened a large kosher section, complete with a kosher bakery and deli, in a nearby location, and the regional supermarket chain Mariano’s added its own dedicated kosher section in Skokie in 2015.

Azulay has pledged to maintain the business as a mainstay of the Chicago-area kosher community. The new owner plans to make some changes, offering expanded bakery, deli and produce sections, and offering kosher cooking classes in the store. Israeli chef Michael Atias, whom Azulay described as “one of the best chefs in the world” and who previously worked at the kosher Soho Bar and Grill in Aventura, Florida, will oversee Hungarian’s new kitchen.

“We’ll try to bring some excitement” to Chicago, Azulay said, noting that Sara’s Tent already enjoys a good reputation with kosher-keeping Chicagoans who visit the Miami area. “A good name is more important than all the profit in the world.”

He plans to renovate the store gradually, without closing for remodeling.

“We hope the community will give us a little time and patience,” Azulay said, “and we’ll be happy to give back to the community as fast as we can.”

“I hope they do,” said Ira Kirsche, as he prepared to finalize the sale and say goodbye to the business he and his family have built over the past 45 years.

As reported by The Times of Israel