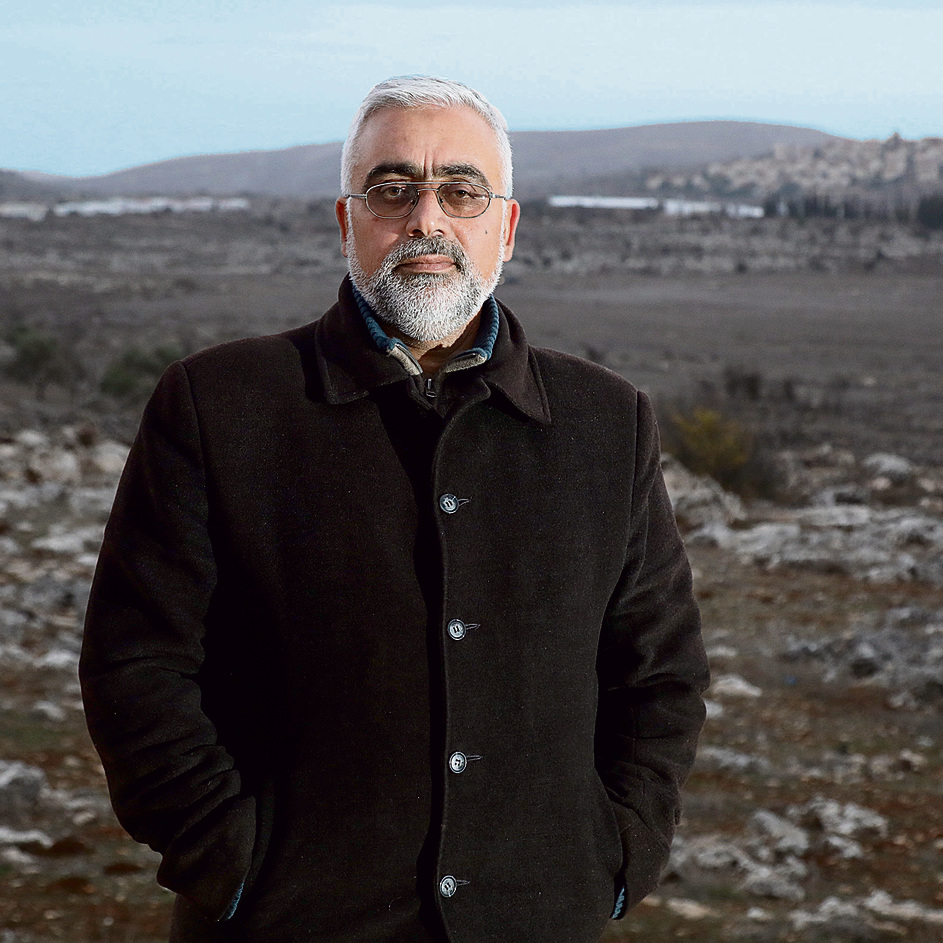

The 2,000 acres that will be expropriated if the Regulation Bill is approved include the Mitzpe Kramim outpost, which was built on land that Hazem Hassim Ajaj says belongs to his family. ‘When I heard that a settlement had been built on my land, I felt as if my hand had been cut off,’ he says, vowing not to give up. Meanwhile, PA teams are monitoring the bill’s progress and collecting data ahead of an International Criminal Court lawsuit.

Our initial plan was to take Hazem Hassim Ajaj from the village Deir Jarir to the hill overlooking the settlement of Mitzpe Kramim. High Court Case 953/11 deals with his claim to regain control of section 13 in parcel 19, on which part of the settlement was built. This land, he says, had been cultivated by his family for decades, until the settlement Kochav Hashachar was built nearby, denying the family access to the land. The plot remained abandoned for years, until the establishment of Mitzpe Kramim, first as a neighborhood at the outskirts of Kochav Hashachar and later as an illegal outpost that became bigger and bigger and currently numbers 43 families.

But the evening began to fall and photographer Shaul Golan begged us to take advantage of whatever daylight was left. So we found ourselves stopping at the side of the road, not far from Ajaj’s house, in the open area directly overlooking the Amona outpost. Ajaj tightened his coat, arranged his collar and looked down at the outpost slated for evacuation following a High Court ruling. But he’s not interested in Amona. He’s interested in the Regulation Bill being devised around the Amona saga.

His petition to the High Court of Justice contains seven dossiers of protocols, documents, the sides’ responses, depositions and aerial photographs. The advocate of the Regulation Bill believe that if it passes in the Knesset, these seven dossiers could then be tossed away and burned, Ajaj’s land expropriated, and Mitzpe Kramim would be made legal by the power of the new law. But Ajaj declares that no Israeli law will keep him away from his land.

“I will never give up,” he says. “My lawyer will continue the battle on my behalf and I will do everything he instructs me to do. If it means having to go to the International Criminal Court in The Hague, we’ll go there.”

The threat of turning to the ICC has been hovering over the Regulation Bill from day one. Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit has warned Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that its approval could lead him to The Hague, and not just him – but also a long list of officials in the political and military echelons.

Is this just an empty threat? Apparently not. Ajaj may not be able to go to The Hague on his own with his lawyer, Hossam Younes, as only a political entity can file a claim with the ICC – like the Palestinian Authority.

A senior PA official we spoke to last week says that the Palestinians have already begun the legal work regarding the Regulation Bill and its implications over a month ago. That work went into high gear after the bill’s approval process began at the Knesset.

“We have a legal team operating in the West Bank and a legal team of experts operating abroad and studying the issue,” he says. “We are collecting data and looking into the possibility of submitting these documents to the ICC in The Hague. If we have too, we’ll definitely go there.”

Peace Now’s recently published Settlement Watch report is all about the numbers behind the Regulation Bill and what these numbers mean. According to Peace Now’s count, which is based on the analysis of aerial shots and master plans of the West Bank settlements, the law will regulate 3,921 housing units by expropriating about 8,183 dunams (2,000 acres) of private Palestinian lands in the settlements and outpost. Fifty-five outposts that have been built illegally on private lands deep within the territories will be able to receive permits and become official settlements.

Looking at what the West Bank map would look like if the law is adopted leaves no room for doubt: The outposts’ regulation will create a sequence of Jewish settlements that will make it very difficult to implement the two-state solution which Prime Minister Netanyahu himself supports in his statements, most recently in an interview with American newsmagazine television program 60 Minutes.

The law—if it passes all Knesset readings—will not apply to cases that the High Court has already ruled on. The court is currently discussing dozens of petitions filed by Palestinians claiming ownership of lands on which outposts and settlements home have been built. The legal proceedings regarding these cases have not been completed yet, and the new law will basically shelve those petitions.

High Court Case 953/11 is one of those petitions whose fate has yet to be decided. The petition was filed by attorney Hossam Younes in November 2011 on behalf of Daud Ahmed Ali Rabia, who claims ownership of section 23 in parcel 19, and on behalf of Ajaj, who claims ownership of section 13 in the same plot. Without getting into the petition, which is laden with details and injunction numbers and different orders, let us just note that Rabia argues that he inherited the section from his grandmother and Ajaj says he bought it from his uncle before he died in Amman, Jordan. All the documents presented by these two men have been added to the petition.

An error became reality

We met on a Tuesday afternoon in a café in Ramallah, not far from Ajaj’s workplace. Rabia was supposed to come too, but a few hours before the meeting he had a heart attack and was rushed to hospital.

“There are maybe 8 kilometers (5 miles) between Deir Jarir and the land under discussion,” Ajaj said, “and the entire area there, not just my section, belonged to people from my village. Kochav Hashachar was built on the lands of Deir Jarir. My section belonged to my grandfather. He had lands which he left for his children. Each one got a piece. I bought this section from one of my grandfather’s heirs, my late uncle Qassem Amer Elshayeb. I grew up on this land. We planted wheat there and there was a well where we would take the sheep to drink.

“As soon as Kochav Hashachar was established, the problems began. The settlers removed us from there, stopped us from coming there with the flock and from growing wheat, and only later said that it was a closed military training area. We lived on that land. All our flock drank from the well that was there. The moment we were banished, my father sold the herd, because we didn’t have another source of water, and became unemployed.”

One can only envy the view Mitzpe Kramim’s residents have. The community is located east of Allon Road and above the Jordan Valley, and the residents see in front of them the whole the valley and the Moab mountains on its eastern side. There are two playgrounds there, mobile homes and a row of permanent houses. Vineyards and fruit trees have been planted alongside the road leading to the community from Kochav Hashachar.

The petition was filed by Ajaj and Rabia against the state and the community’s residents. The residents argued in response that it was the state that built the outpost, and that the state must reach an agreement with the petitioners—if they really do own the land—and compensate them with money or alternative land.

The state confirmed in its response that sections 13 and 23 in parcel 19 are regulated private property beyond the jurisdiction of the Mateh Binyamin Regional Council. The land remained empty until Independence Day 1999, when Mitzpe Kramim was established south of Kochav Hashachar. Eight months later, the residents were evacuated from the place as part of the outpost agreement signed between then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak and the Yesha Council heads. The agreement stated that the outpost’s buildings would be moved into Kochav Hashachar. Instead, the caravans were moved to their current location.

Aviad Caspi, head of infrastructure at Israel’s Civil Administration, referred to the caravans’ move to the current place as “an error.” Error or not, Mitzpe Kramim has developed since then, and today the two sections that Rabia and Ajaj have claimed ownership of include 35 caravans and four permanent buildings, with a total of 150 residents. The entire outpost, which is defined as illegal, has 43 families with some 150 children.

In November 2013, the outpost’s residents filed a civil claim with the Jerusalem District Court against the state and the two Palestinian petitioners, demanding that the two sides reach a settlement that would allow the residents to remain in their homes. Attorney Younes, representing the two men, said that the claim’s goal was to delay the High Court proceedings. A year later, in November 2014, the High Court issued a conditional order against the state and Mitzpe Kramim’s residents, essentially accepting Rabia and Ajaj’s claims. No new developments have been recorded since then.

In November 2015, the state turned to the High Court and asked to wait for the completion of the District Court proceedings. The High Court gave the state 18 months. In the time that has passed since then, there has been hardly any progress.

“There is half a year left till the end of the extension granted by the High Court,” attorney Younes sighs, “and I’m telling you that there is no chance the District Court proceedings will be completed by then. The state’s interest is to delay the decision as much as it can. That’s the last thing they need, a new Amona in half a year’s time.”

The Regulation Bill will basically cancel the petition.

“Not just that one. I am running a number of High Court petitions regarding private lands with outposts on them. I have a High Court petitions over plots on one of the hills in Eli, in Beit El, in Givat Asaf, and even in Amona. If the law legitimizing land theft passes, the Palestinian petitioners will no longer have any place in the Israeli legal system. The only option they will be left with is international. To sue not only the responsible people in the Civil Administration, in the army and in the political echelon, but also the settlers themselves whose names and details we already have.”

Ajaj claims that for many years he didn’t even know that he could turn to the Israeli court. “I didn’t know that the Israeli law could come to my aid,” he says. “As soon as I was told that I could petition the court in Jerusalem, I did it immediately.”

We explained to him that the new law states he is entitled to pecuniary compensation for his land, if it indeed turns out that he is the owner. Ajaj was unmoved. “I’m firmly against any compensation. Money comes and goes, but the land stays. I’ll say more than that: The settlers say that they invested money in the place, that they built infrastructures and homes at a value exceeding the value of the land. I’m willing to pay back everything they invested, as long as they leave the homes and go away, despite the fact that they forced me out of the land, that they forcibly took it away from me. When I heard that a settlement had been built on it, I felt as if my hand had been cut off.”

Do you have that kind of money?

“I don’t, but I assume that any bank in Ramallah will give me a loan for this purpose.”

Fear of arrest warrants

Meanwhile, the Palestinian Authority is preparing files on each and every one of the petitions and collecting data. A file is also being prepared on the Regulation Bill itself ahead of a possible lawsuit at the International Criminal Court.

The Defense Ministry’s legal advisor, Ahaz Ben-Ari, and Deputy Attorney General Roy Schöndorf were at the Knesset recently to speak at a meeting of the committee appointed to handle the Regulation Bill as part of the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee. Channel 10 reporter Akiva Novick published some of their comments.

According to the report, Ben-Ari said: “The defense establishment opposes this law, clear and simple. I find it difficult to believe that such a law would pass in Israel. Netanyahu said it was a recipe for reaching The Hague. Is there a public servant who will dare sign an expropriation order?”

According to the same report, Schöndorf added that “an investigation in The Hague has many implications on the individual level. An authority to prosecute, personal arrest warrants.”

The senior PA official’s comments emphasize the legal advisors’ stand: “Our work on the ICC file is daily and routine. The data being collected there includes anything new that occurs in regards to the settlement enterprise. The teams are collecting findings and information, which are handed over to jurists who examine them.”

The source notes that there is also a Palestinian team which is closely monitoring the progress of the Regulation Bill. He clarifies, however, that at this stage the PA is inclined to raise the issue at the UN by proposing a Security Council resolution. If the Palestinians don’t get what they want there, the next stop will be The Hague.

As reported by Ynetnews