Addressing a growing problem in the country, lawmakers took the first step on Thursday to curb the mounting numbers of murders that go unpunished.

ISLAMABAD — Despite objections from religious hard-liners, lawmakers Thursday took the first significant move to curb mounting numbers of “honor” killings in Pakistan, stiffening the penalties and closing a loophole that allowed such killers to go free.

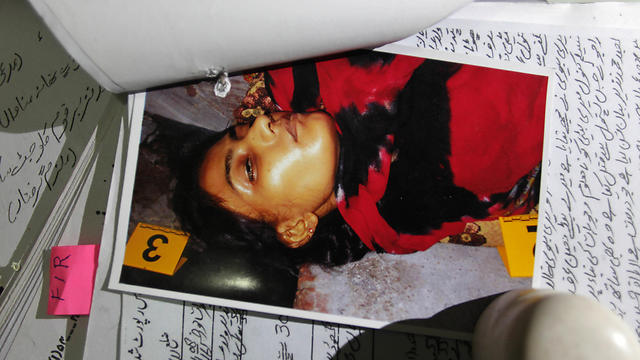

Public outrage has been growing in Pakistan in the wake of a string of particularly gruesome slayings.

More than 1,000 women were killed last year in so-called honor killings in Pakistan, often by fathers, brothers or husbands who believed the victims had tainted the family name by marrying the man of her choice — or even meeting or being seen sitting with a man.

Those who carry out such killings are almost never punished. In accordance with Islamic Shariah law, Pakistan’s legal code since the 1990s has allowed families of victims to forgive the killer. Since the killers in these cases are usually close relatives, the family almost always forgives them.

The measure passed Thursday imposes a mandatory 25-year prison sentence for anyone convicted of killing in the name of honor and bans family members from forgiving them.

Relatives can only forgive an honor killer who has been condemned to death, in which case the sentence is commuted to prison.

Activists and liberal opposition members who backed the law said it was a step in the right direction, although they said it should have gone further to eliminate forgiveness.

“Remove these clauses which allow the option of forgiveness, otherwise these killings will keep happening,” warned Sherry Rehman, an opposition legislator and fierce champion of women’s rights in a speech to parliament.

She pointed to the Oscar-winning documentary “Girl in the River” that told the story of a girl who survived an attempt by her uncle and father to kill her but then was forced to forgive them.

“We should be ashamed. We should all be ashamed. You should all be ashamed,” she said of the forgiveness provisions. The film prompted Pakistan’s conservative Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to promise legislation to end the practice.

Only about a third of the 446 lawmakers attended the session, but debate was raucous, with the loudest opposition coming from hard-line Islamists.

Conservative Sen. Hafiz Hamdullah said parliament should instead address elopements by women, claiming 17,000 had done so since 2014.

“Why don’t we see what are the reasons behind such killings? Why are girls eloping from their homes?” he said.

Speaking later to The Associated Press, he echoed a stance taken by many hard-liners that the law is bringing Western-style independence for women.

“They are trying to impose Western culture over here. We will not allow (it),” he said. “We will impose the law that our holy Quran and Sunnah (tradition) say.”

Conservatives demanded that the Islamic Ideology Council, a body of conservative Muslim clerics, weigh in on the bill before the vote. Supporters flatly refused, saying the council routinely vetoes legislation aimed at protecting women. The council once ruled it was permissible for a man to “lightly” beat his wife, though recently it did say that honor killings are “un-Islamic.”

In the end, a voice vote was held, with a strong “yes” vote and a low mumbling of those opposed.

Government lawmakers, who had pushed the law, said they spent nearly a year negotiating with Pakistan’s many political parties to get a draft that had a chance of passing.

Zafarullah Khan, a legal adviser to Sharif, said the bill was a compromise.

“This was the best possible solution,” Khan said in an interview. It offered a concession to religious parties, while still ensuring a convicted killer spends 25 years in jail, he said, adding that what needs to change is the “mindset” of fathers and brothers, families and witnesses.

“The problem is societal behavior,” Khan said. “It has nothing to do with laws.”

Honor killings are rooted in traditions by which a family’s honor is bound up with a woman’s chastity. Such killings often are met with acceptance, even approval, by neighbors and relatives.

A man who killed his sister for marrying without family approval described how his co-workers taunted him relentlessly, even telling him he should kill her.

But public outrage over the practice has also been growing as proliferating TV channels and more access to social media have lifted the secrecy that once surrounded the killings.

In recent months, a social media celebrity, Qandeel Baluch was choked to death by her brother; a mother, with the help of her son, strangled and set fire to her daughter because she married the boy of her dreams; a teenage girl was tied up in a car and set ablaze on orders of tribal leaders because she helped a friend elope.

The legislation was originally introduced nearly a year ago by the opposition People’s Party. But because the practice of forgiveness is part of Shariah, Parliament deferred it to a committee to try to build a consensus. The conservative Pakistan Muslim League took up the bill but added the possibility of forgiveness for the death penalty as a concession to religious parties.

“We have to work within certain confines … but we have taken this step and we have come so far,” said Shaista Pervaiz Malik, a government lawmaker.

A second bill was also passed Thursday that sought to make it more likely to get a conviction in the case of rape.

The measure, passed with little debate, allowed medical evidence to be admitted in court as well as the use of DNA, which had been opposed by religious hard-liners. It’s not clear what prompted them to suspend their objection.

Previously, medical evidence was not enough for conviction, and instead four witnesses to the rape were necessary under Islamic law. In the past, the culprit simply accused the victim of being a willing partner, which often landed her in jail.

As reported by Ynetnews