A significant amount of Jewish Britons, dismayed at the UK’s decision to exit the European Union, have decided to seek the German citizenship that their forebears lost under the Nazi regime.

London — For London rabbi Julia Neuberger, Britain’s vote to leave the European Union has had a very personal impact: She has decided to seek German citizenship, laying to rest her family’s painful legacy of the Nazi era.

Neuberger is among a significant number of Jewish Britons whose dismay over Brexit has led them to invoke a German law allowing people stripped of German citizenship by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945, and their descendants, to have it restored.

“It was Brexit that tipped me off, but now in my mid-60s I feel like I’ve made my peace with Germany and this step will only take me closer,” said Neuberger, whose mother left Germany for Britain in 1937 to escape Nazi persecution of the Jews.

Now, a German passport holds the promise of a future with full access to the EU and its practical benefits such as freedom to travel, live and work anywhere in a bloc that has 27 other nations – rights that Britons may no longer enjoy after Brexit is enacted.

Some of Britain’s estimated 260,000 Jews remain implacably opposed to the idea, and for Neuberger too the decision to apply for German citizenship taps into deep emotional baggage due to the weight of history.

“My daughter asked ‘why would you want to do this after all they did to us?’,” said Neuberger, senior rabbi at the West London Synagogue and a member of the House of Lords, the upper chamber of the British parliament. “But there is some German in me after all and it goes very deep.”

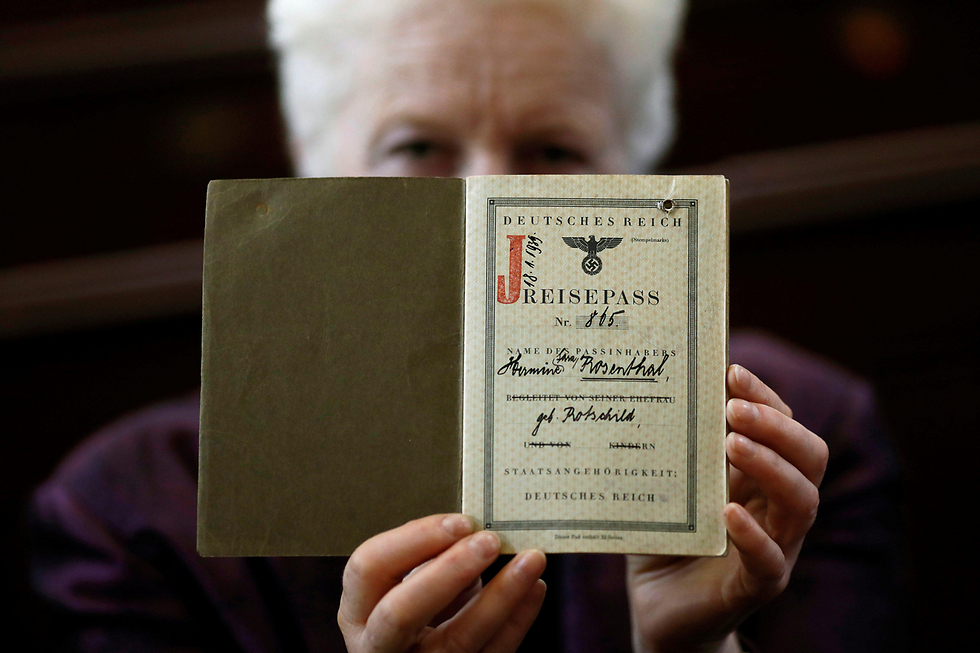

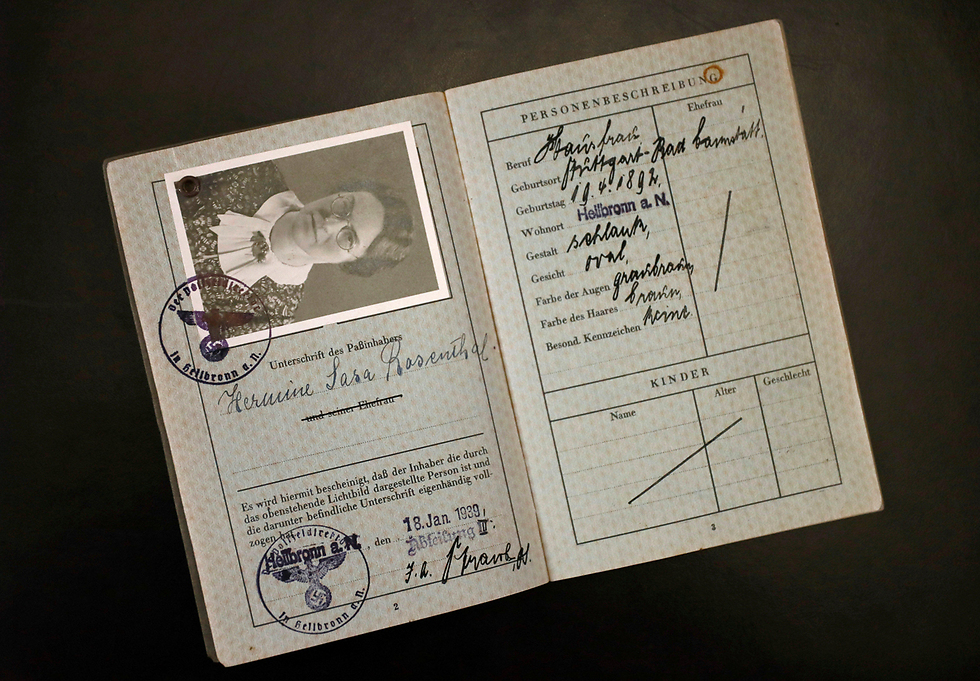

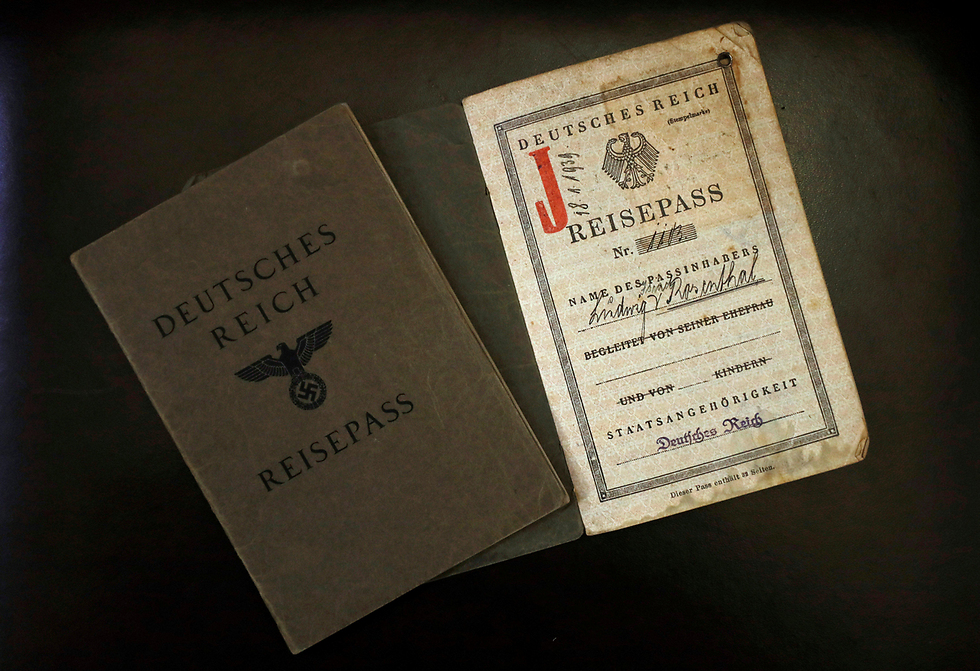

Neuberger, whose application is being processed, still has her maternal grandparents’ old German passports. Their covers bear a black eagle with outstretched wings perched on a swastika, and the first inside pages are stamped with a red “J” for Jew.

It is a remarkable twist of history that Jews who lost family members in the Holocaust are now using such old documents to obtain modern Germany’s maroon-colored passports.

Germany’s Foreign Ministry said that since the Brexit referendum in June, the London embassy had received about 400 inquiries about how to apply for German citizenship under article 116 of the country’s post-war Basic Law, and about 100 applications.

That compares with about 20 inquiries per year previously.

‘Turn in her grave’

More than 17 million Britons voted on June 23 to leave the EU for a variety of reasons, including a desire to regain national control over immigration from the bloc.

However, a further 16 million voted to remain and many are anxious about the practical and symbolic consequences of leaving a union that was born out of a post-war determination to bring Europeans together.

Authorities in Dublin also reported a rush of citizenship inquiries from Britons of Irish descent after the referendum.

Like other British Jews seeking German citizenship, Neuberger intends to stay in Britain. She is one of a number of family members who have reached prominence in the nation’s public life – her husband is a leading academic and her brothers-in-law include the president of the supreme court.

At a recent gathering of about 100 members of the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) in London, called to mark the organization’s 75th anniversary, discussion was dominated by the issue of whether to make an article 116 claim.

“The idea shocked many at first,” said Michael Newman, 41, chief executive of the AJR. “We all don’t know what the future will hold and want to make sure that we, but also mainly our children, continue to have access to Europe.”

While it may be a mostly practical step for younger people, the emotional toll is much higher for older people who have vivid memories of their own escape or grew up listening to their parents’ painful memories.

“When my son told me after the vote he’d apply I was horrified and said my mother would turn in her grave,” said Frank Harding, who is in his 70s. His parents fled to England in the 1930s.

He said his son’s decision initially felt like a betrayal of his parents, who boycotted German products and never allowed them in their house.

But he said he now understood his son’s decision and thought it important for the younger generations to keep the door to Europe open. “It certainly is also a form of reconciliation, but I still haven’t decided if I will apply myself,” said Harding.

The AJR estimates that around 70,000 Jews from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia arrived in Britain before World War Two.

Austria has a similar law to Germany’s article 116 but authorities in Vienna did not respond to requests for information about applications from Britain since the Brexit vote.

Numbers of article 116 applications from Jewish Britons could increase further. Many of the people interviewed by Reuters at the AJR meeting said they were waiting for the terms of Brexit to become clear before taking a final decision. Negotiations have yet to start and when they do, they are expected to last two years.

“I’m not sure people would have done this at any point under regular circumstances,” said Anthony Grenville, an author and the son of Austrian refugees. “It took Brexit to push British Jews to consider this option.”

As reported by Ynetnews