Salt Lake City – Bob Ebeling spent three decades filled with guilt over not stopping the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, but found relief in the weeks before his death.

Ebeling’s daughter Leslie Serna told The Associated Press that her father died Monday at the age of 89 in Brigham City, Utah.

She said he was finally able to forgive himself thanks to the hundreds of supportive phone calls and letters he received following a January NPR story about the 30th anniversary of the Challenger disaster. She said they tried to ease Ebeling’s guilt, and he was soon able to let go.

“It was like the world gave him permission, they said, ‘OK, you did everything you could possibly do, you’re a good person,’” Serna said.

Ebeling was a booster rocket engineer at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol in 1986. He and a handful of his colleagues worried that the cold temperatures the night before the Challenger was set to launch would harm the rubber O-ring seals and allow burning rocket fuel to leak out of booster joints, NPR reported.

Ebeling warned his boss the morning before the launch of the dangers that could face the Challenger if it was sent into space that day. He collected data that illustrated the risks and spent hours arguing to postpone sending it and its seven astronauts into space.

Serna said she also worked for NASA at the time and would carpool to work with him. The morning of the launch, Ebeling picked her up and beat his hand on the dashboard, angry he had not convinced NASA to postpone the launch.

Serna said his guilt reached such intense levels that he told her the only way he could have gotten them to postpone the flight was if he had brought a gun to work and held them hostage.

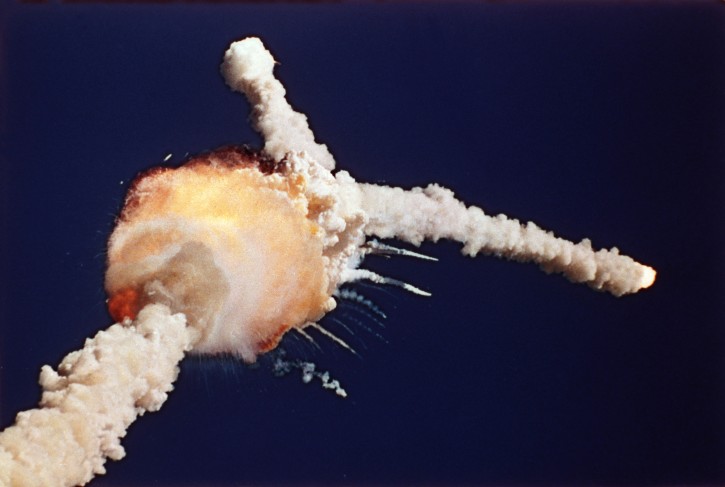

She and her father watched live video of the Challenger clearing the launch pad on January 28. She said Ebeling leaned over to her and said, “It’s not over.” About 20 seconds later the shuttle exploded.

“My dad just started shaking and weeping,” she said.

After about two decades working for NASA, Ebeling retired a few months after the disaster.

He soon shifted his focus to conservation work. Serna said he and his wife devoted hundreds of hours to rebuilding a bird refuge located near him.

“It was his way of trying to make things right,” she said.

A few years later he was awarded a prestigious award by then President George H.W. Bush for his conservation work.

Serna described her father as a very generous man with a great sense of humor.

As reported by Vos Iz Neias