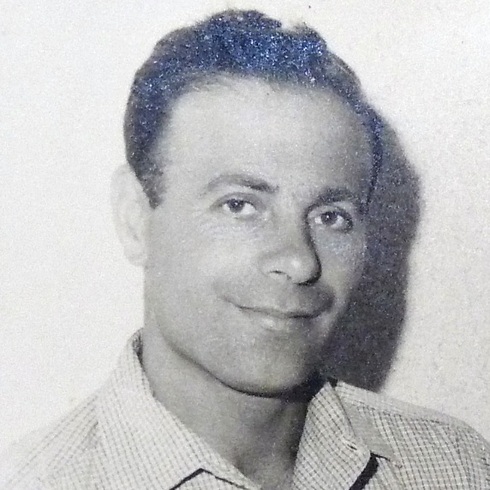

“I didn’t want to die in a crematorium, so I decided that they would have to shoot me,” recalled Michael Lizrovitch, today 89 years old. “I took pliers, and in the dark of night and heavy rain, I ran to the electric fence. To my surprise, I escaped with my life.”

A week after the death of the “last witness from Treblinka,” Shumel Vilnberg, another story of a survivor of the death camp who managed to survive the inferno and stay alive came to light.

In contrast to Vilenberg, who was the last of the Jews who escaped from Treblinka during the revolt at the camp, Lizrovitch was one of the few who succeeded in escaping on his own beforehand, and without any connection to the revolt. According to Yad Vashem, two other Treblinka survivors are still alive – one lives in the US while the other one lives in Sweden.

The death of Shmuel Vilenberg, known as “the last witness of Treblinka,” sparked renewed interest in the Lizrovitch story. His family worried over the years that the heroic story of the family’s patriarch was ignored, and sought to fix an historical injustice.

“Shmuel Vilenberg it seems was the last survivor of the members of the revolt who managed to escape, but my grandfather managed to escape from the camp by himself,” explained Lizrovitch’s granddaughter Yifat Shaul, 27. “It is very important that the story of my grandfather be told. In the years that passed I turned to Yad Vashem and tried to push the matter, but it seems that my grandfather’s testimony slipped through the cracks.”

Michael Lizrovitch was born in 1927 to a family of five brothers. During World War II, the family was moved to a ghetto in the town of Czestochowa, where the whole family lived in one small room. His father, Lizrovitch testified, worked as a beer bottler in a factory on the front yard of the house.

Seven years ago, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and therefore his 1992 testimony at Yad Vashem is the one and only testimony about his life during the Nazi regime.

“When the Nazis rose to power, I immediately understood that my childhood was over,” he said. “I understood that from now on going forward, it would only be bad, although there was the hope that something would change and we’d be able to get out alive.”

In 1942, after Yom Kippur prayers in the synagogue, the Jews of Czestochowa were gathered in the town square. Lizerovitch, who was 13 at the time, understood that this was probably the selection for those who were to go to Treblinka, and that they would not survive.

“My mother left us and said that she hoped that after the war we would all meet again,” Lizerovitch said. “We thought at first that we would be put to work, although there were rumors that those who go to Treblinka never leave.”

After two days of traveling by train, they arrived at Treblinka. Because he had a small album of stamps hidden in his pocket, he was sent to work in cataloguing the items which were taken out of the Jews’ suitcases.

“My job was to sort the possessions into piles. There were huge piles of watches, shoes, eyeglasses, and other things. When I heard women’s screams coming from the crematorium, and afterwards dead silence, I understood that these were those women’s items.”

After two weeks in the camp, as Lizerovitch attested, the Kapo told him that the “the next day, you will be gone.”

“At that moment I thought that maybe I should try to escape,” Lizerovitch said. “Since I was going die anyway, I decided that I wasn’t going to die in the crematorium. I didn’t think that I would actually succeed – I thought to myself that it’s better to die by getting shot. That was what I planned for.”

He continued, “From the piles of possessions I took a stocking cap, and inside I put money and rings, and I also put on several watches so I would have something if I managed to escape.”

“That night in the barracks, I dreamt that my mother and father were next to me, and they told me ‘go now’. I immediately woke up, opened the door, and outside there was a torrential downpour. I took electric pliers and planned to run towards the electric fence underneath the guard tower.”

The heavy rain brought with it a heavy darkness to the camp. After running to the electric fence, Lizerovitch found himself under the guard tower, alive.

“I cut the barbed wire with the pliers, and immediately sprinted out. The stocking with the money got stuck in the fence, but I didn’t care and continued to run. After a few hours of running, I realized that I had run in the wrong direction, and that I was only two kilometers away from the camp.”

After his escape, Lizerovitch hid in the village close by, and with the help some of the local Poles, managed to obtain a train ticket to Warsaw. From there, he took a train to Czestochowa, where he hid out for the rest of the war.

Lizerovitch moved to Israel in 1946, where he met his wife Judith. They settled down in the city of Haifa, where they started a new family with two sons, six grand children, and a great-grandchild.

As reported by Ynetnews