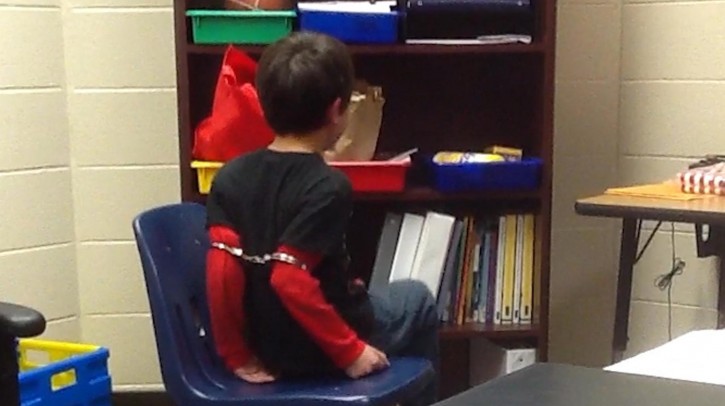

Louisville, KY – The boy sat in a chair, the sound of his whimpering interrupted briefly by the clank of metal handcuffs closing around his arms.

“You don’t get to swing at me like that,” a deputy says to the 8-year-old child, the interaction caught by a video camera. “You can do what we asked you to, or you can suffer the consequences.”

The video — entered as Exhibit A in a lawsuit the ACLU filed against the school, the sheriff and the officer — rocketed across the Internet on Tuesday and was shown again and again on cable news, reigniting a fierce debate over aggressive policing in public schools.

The sheriff defended his deputy while experts insisted that children shouldn’t be treated like adult criminals and bemoaned the lack of standardized regulations for restraining children.

“It was hard to breath,” David Shapiro, who leads the National Juvenile Defender Center’s campaign against child shackling, said of his reaction when he first saw the video. “As someone who has acted out in class before, I really felt for that child. That’s not the way to treat any child, in school, in court, or anywhere.”

“Oh my goodness. Oh, no, this is not good,” groaned Steven C. Teske, a Georgia juvenile court judge who has led the charge to reduce restraints in schools, as he watched the video for the first time while on the phone with The Associated Press.

The lawsuit filed by two mothers alleges that school resource officer Kevin Sumner, a Kenton County deputy sheriff, handcuffed two children, the 8-year-old boy in the video and another 9-year-old girl in schools in the Covington Independent School District. Both children have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and are identified in court records only by their initials. It’s also not clear who took the video, which was filmed in August.

The handcuffs were too big for the children’s wrists, so Sumner put the cuffs around their biceps, the lawsuit alleges.

In the video, the boy, who weighed 52 pounds, cried. “Ow, that hurts,” he says.

The boy had been removed from class for failing to follow his teacher’s instructions, the lawsuit says. He tried to leave the principal’s office, so administrators stopped him until Sumner arrived. The officer took him to the bathroom and the boy tried to hit Sumner with his elbow.

Attempts to reach the school district were unsuccessful, but Kenton County Sheriff Chuck Korzenborn defended his deputy, who he described as a respected and skilled officer valued by the community.

School administrators’ asked for his help after their “efforts to deescalate and defuse a threat to others had proven unsuccessful,” Korzenborn said in a statement. “Deputy Sumner responded to the call and did what he is sworn to do and in conformity with all constitutional and law enforcement standards.”

Kentucky state regulations ban school officials from restraining students in a public school unless the “students’ behavior poses an imminent danger of physical harm to self or others.” It also forbids personnel from restraining students that they know have disabilities that could cause trouble.

The lawsuit says officials at both schools were aware of the students’ disabilities, which include “impulsivity, and difficulty paying attention, complying with directives, controlling emotions and remaining seated.”

“An 8-year-old’s job description is to be impulsive,” said Julian Ford, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder compounds that problem, he said, struggling to think of a scenario where handcuffing an 8-year-old might be necessary.

“It helps the adults a lot more than it helps the kid,” he said.

In the video, the boy kicks his legs in the chair.

Sumner bends down and puts his hand on his shoulder.

“Look at me for a minute, look at me,” he says. “If you want the handcuffs off, you’ve got to stop kicking. Do you want them off or not? It’s up to you if you want them off.”

“I’m devastated to see a child treated this way,” said Lisa H. Thurau, founder Strategies for Youth, an organization meant to improve the relationship between children and police. “But this is not an isolated case. We’ve heard of these cases before.”

Districts across the county began placing officers in school in the early 1990s and the practice exploded in 1999, after two teenagers massacred their fellow students at Columbine High School in Colorado.

In the years since, the line between police officer and school administrator had been muddled, experts say. Schools now commonly call on their in-house officers to implement routine discipline.

At the same time, there has been no uniform method of training officers, no universal oversight or standardized guidelines, Thurau said.

Children with disabilities make up 12 percent of the public school population. But they make up 25 percent of all school arrests.

Thurau hopes that the video might spur the public to demand change.

“The video makes it very clear what’s happening out there,” she said. “And I think that there’s an increasing awareness among folks that this has really, really got to stop.”

As reported by Vos Iz Neias