When two kingdoms emerged in Eretz Israel, they quickly devolved into civil wars and eventually, exile; What stoked this division? Who was the prophetic voice of reason, and what timeless cautionary tale does this biblical story provide?

The judicial reform that is increasingly polarizing the people of Israel into two separate camps has given rise to civic initiatives calling for a separation between “Israel” and “Judah.”

In contrast to the latter, which would be conservative-religious and include Jerusalem as well as the West Bank, they propose the establishment of a liberal Israel that would encompass Tel Aviv and the coastal plain cities.

These calls are not yet mainstream, perhaps even fantastical, but they are consistent and their reference is clear: the Biblical separation between the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, which lasted for centuries and was interrupted only by the exile of Israel.

It seems that those indulging this idea, which appears risky to some and compellingly realistic to others, have not really examined the original event—those two kingdoms that once existed in Eretz Israel. In their glory days, they extended as far as the Euphrates River—today’s Iraq—and in less fortunate times were awash with blood, loss and exile.

Countless books have been published on the interaction between the kingdoms, but in this context, I would like to briefly touch on two major events mentioned in the Bible, and then cautiously wonder: Are they indeed relevant to us? The answer may be both frightening and hopeful.

The separation of the ancient kingdoms

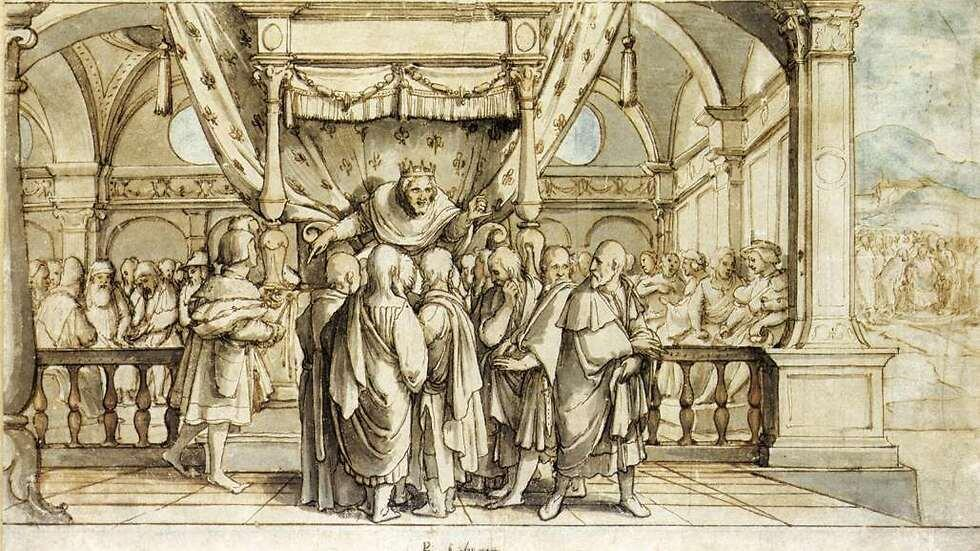

Disturbing hints about not entirely healthy relations between “Israel” and “Judah” are scattered throughout the Bible. However, the formal separation between the two groups only occurred after the death of King Solomon.

The crown was supposed to smoothly pass to his son Rehoboam, but he acted unwisely. When the Israelites asked him to lighten their tax burden, he responded harshly, guided by the advice of his young counselors.

These calls are not yet mainstream, perhaps even fantastical, but they are consistent and their reference is clear: the Biblical separation between the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, which lasted for centuries and was interrupted only by the exile of Israel.

It seems that those indulging this idea, which appears risky to some and compellingly realistic to others, have not really examined the original event—those two kingdoms that once existed in Eretz Israel. In their glory days, they extended as far as the Euphrates River—today’s Iraq—and in less fortunate times were awash with blood, loss and exile.

Countless books have been published on the interaction between the kingdoms, but in this context, I would like to briefly touch on two major events mentioned in the Bible, and then cautiously wonder: Are they indeed relevant to us? The answer may be both frightening and hopeful.

The separation of the ancient kingdoms

Disturbing hints about not entirely healthy relations between “Israel” and “Judah” are scattered throughout the Bible. However, the formal separation between the two groups only occurred after the death of King Solomon.

The crown was supposed to smoothly pass to his son Rehoboam, but he acted unwisely. When the Israelites asked him to lighten their tax burden, he responded harshly, guided by the advice of his young counselors.

According to his words, not only did he have no intention of reducing the tax rate, but he also planned to rule with an even heavier hand than his father Solomon. In his own words, “Whereas my father scourged you with whips, I will scourge you with scorpions.”

At the forefront of the people’s representatives stood a young man named Jeroboam son of Nebat. Who was this man? A short time before Solomon’s death, a young man from the tribe of Ephraim appeared before the aging king and criticized him and the crowd present for building unnecessary boondoggles for his wife, the daughter of Pharaoh.

Jeroboam later fled to a hiding place in Egypt, and now he had returned with the people’s representatives to demand social justice from the new king, who, as mentioned, chose to respond harshly.

The people were, of course, hurt by the cynical response of the young king and decided to rebel against him. “What share have we in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents, O Israel!”

At this point, Rehoboam still tries to assert his control and sends after them Adoram, who was “over the tribute,” but the people stone the king’s envoy to death, and Rehoboam narrowly escapes to Jerusalem.

The people of Israel send a call to Jeroboam, who has in the meantime returned to his home, and they make him their king. Jeroboam goes to Ephraim, builds Nablus, and effectively becomes the king of Israel, while Rehoboam remains in Jerusalem.

Now there were two kings in Eretz Israel: Rehoboam ruled over Judah and Benjamin, and Jeroboam ruled over the remaining ten tribes.

(Photo: Reuters)

Everything went as well as possible for Jeroboam, who controlled almost the entire kingdom, except for one issue that disturbed him: the pilgrimage festivals. He feared that when the people would go up to Jerusalem to celebrate the three pilgrimage festivals—Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot—and perform the rites of sacrifice, Rehoboam would exploit his local control over Jerusalem and the Temple. The people, who would be under the festive influence of the pilgrimage, would then see him as the only legitimate king.

What to do? Jeroboam takes preventative action: he constructs two golden calves and places them at strategic locations—one in Bethel, which now becomes a holy place, a dwelling for God; and the other at the northern border of the Kingdom of Israel, in the region of Dan. He proclaims the two calves as “gods” and asks the people to visit them and worship them: “Behold, your gods, O Israel.”

He also announces a new festival—an alternative to the traditional Festival of Sukkot. This new “Festival of Jeroboam” is scheduled exactly one month after the date of the original festival—on the 15th of the month of Cheshvan. On the day of the festival, by the way, as Jeroboam stands happily over his altar, a prophet from Judah, a “man of God” named Iddo, appears and delivers a harsh prophecy. Jeroboam raises his hand and orders Iddo’s capture—“Seize him.” In response, God withers his hand.

Not much time passes, Rehoboam dies, and his son Abijah ascends to power. Jeroboam prepares for war against him, and Abijah proclaims angrily, “Jeroboam son of Nebat, servant of Solomon son of David, rebelled against his lord.” Jeroboam is unimpressed, tries to ambush his rival’s army, but is defeated in battle. The dire result: 500,000 Israelite soldiers fall in battle.

Some key terms

So what do we have? A king who is unaware of the spiraling cost of living in Israel; when the masses rise up, he listens to the advice of his close friends, those to whom he perhaps feels obligated—even though they are young, and perhaps even inexperienced. Then, when he faces popular protests, he tries to sic on them his stern tax collector. The result: the officer is stoned to death, the king flees and the people split into two dichotomous groups.

“Israel has recorded 24,000 victims of war and terrorist acts since 1860 to the present day. According to scripture, in this first civil war, half a million people perished”

If any of the readers spot key terms such as housing prices and the cost of living, influence and appointment of cronies, ignoring the voice of “experts” and professionals, social unrest, police brutality, youth uprising, officials subservient to the appointed minister, calls for civil disobedience and the uttering of irresponsible and potentially disastrous slogans, they do so at their own risk.

What else did we have? A political, geographical, and ethnic split that quickly turns into a religious conflict. Jeroboam understood that the original holy sites were in the hands of his rival, so he created new gods, built altars for them and declared a new holiday. The political got mixed up with the religious, a “confrontation” with the man of God and shortly thereafter a “regular” war occurs.

(Photo: Reuters/Amir Cohen)

If any of the readers spot key terms such as culture war, religious, liberal or conservative values that include the tough questions about self-determination, attempts to neutralize the gatekeepers who threaten the monarchy, the intervention of a “higher power” that protects the “gatekeeper,” then the question arises as to who exactly decides who the relevant “gatekeepers” are, the ruler’s fear of losing power, perhaps even fear of religious or civil prosecution, bringing sacred values close for the sake of holding onto power or for the sake of removing a political rival from power and suppressing personal and public fears, and the willingness to start a civil war because of all of the above—they do so at their own peril.

Israel has recorded 24,000 victims of war and terrorist acts since 1860 to the present day. According to scripture, in this first civil war, half a million people perished.

The Kingdom of Israel goes mad

Let’s skip 220 years into the future. At the head of the Kingdom of Judah stands a king named Ahaz, and a king named Pekah in Israel. The latter establishes a relationship with Rezin, the king of Aram in the north (today’s Syria), and forms a coalition against the Assyrian Empire that aims to annex Israel.

Pekah understands that he needs additional forces for the coalition against the Assyrian threat and turns to King Ahaz of Judah. “Come and join me in the anti-Assyrian royal axis.” Without going into the (fascinating) details that made up Ahaz’s considerations, let’s summarize that the Judean, who was characterized by a fearful and obsequious nature, refused the Israeli’s offer.

Pekah, a not particularly gentle king, is furious and goes to war against Ahaz. The results are disastrous for the Judeans. “And Pekah son of Remaliah killed in Judah one hundred and twenty thousand in one day, all valiant men.”

“And with their feet in rivers of blood, a long convoy of 200,000 women, children, and girls stood. Their clothes torn, their bodies carried the marks of lashes and they stood humiliated, beaten and degraded, waiting for their fate: a life of slavery”

But it doesn’t end there: “And the children of Israel took captive of their brethren three hundred thousand, women, and sons, and daughters, and they spoiled them of much property.”

Try to imagine the bedlam in the Jerusalem area. Within 24 hours, rivers of blood flowed from the bodies of 120,000 Jerusalemite soldiers. Naturally, more streams flowed from the dead who fell on the additional front opened against Aram.

And with their feet in rivers of blood, a long convoy of 200,000 women, children, and girls stood. Their clothes torn, their bodies carried the marks of lashes and they stood humiliated, beaten and degraded, waiting for their fate: a life of slavery.

But then a bright, piercing ray of light halts stops the frenzy of the Israeli soldiers. A prophet named Oded arrives at the bloody and horrifying scene, and raises his voice. “You have slaughtered them in a rage that reaches up to heaven, and now you are saying to subdue sons of Judah and Jerusalem for menservants and for maidservants for yourselves.” In a loose interpretation, he says: ‘Guys, what is going on with you?

The cries of the 120,000 dead, whom you showed no mercy, have reached the heavens, and now you are also collecting hundreds of thousands of women, children and girls to be your menservants and maidservants?

(Photo: Shaul Golan)

It is not hard to imagine the silence that followed Prophet Oded’s thunderous voice, and the discomfort people felt when the dreadful truth was thrown in their faces. Four army commanders—Azariah, Berachiah, Hezekiah and Amasa—turned to their brothers and said to them: “Enough. We’ve gone too far. We’re already drenched in sin, is this what we need now?”

The soldiers looked at each other and then collectively released the captives. The four great warriors took care to dress the downtrodden, to anoint their wounds, and to arrange for their transportation back to the cities of Judah.

“And all the men who were with them took from the spoil and clothed them, shod them, fed them, gave them drink, anointed them, and led all the feeble among them upon donkeys, and brought them to Jericho, the city of palm trees, to their brethren.”

Israel and Judah 2023

Imagine that Israel and Judah are divided. The right-wingers, the conservatives, the ultra-Orthodox and the religious nationalists mostly concentrate in one area; the liberals, the leftists and the progressives concentrate in their own enclave.

In the beginning, maybe even in the first 220 years, there are no major wars. But then, due to a national, political, cultural or economic rift, one of the groups forms a coalition against the other. One joins France, and the other the United States; one with Russia, and the other with Ukraine; one with Bahrain, and the other with Jordan.

(Photo: Yuval Hen)

Proposals for shared governance are rejected by the leaders of the groups and a devastating civil war breaks out. Not hundreds of thousands, but millions of soldiers perish from both sides, and the women, children and young girls become humiliated victims of the other group that seeks to enslave them to a new culture, either conservative or liberal, which they did not know before.

But then a bright, piercing ray of light shines through and stops the madness. A high-profile, moderate and beloved figure arrives on the bloody and horrifying scene and raises its voice. “Friends, what is wrong with you?”

Perhaps it’s time to remember that “After being forcibly exiled from their land, the people kept faith with it throughout their Dispersion and never ceased to pray and hope for their return to it and for the restoration in it of their political freedom.”

He is also happy to remind us that “The catastrophe (Holocaust) which recently befell the Jewish people – the massacre of millions of Jews in Europe – was another clear demonstration of the urgency of solving the problem of its homelessness by re-establishing in Eretz-Israel the Jewish State.”

And then, after separating from the millions who were brutally slaughtered by the Nazis, we arrived, beaten, wounded and disillusioned, partners in the “covenant of fate” (as coined by Rabbi Soloveitchik) but also full of hope toward the “covenant of destiny”—to that Friday on which ‘We hereby declare the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel, which will be based on the foundation of liberty, justice, and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel.” Have we learned nothing?

What sparked this crisis and what’s the endgame?

“The crisis between the kingdoms is rooted not only in Ahaz’s refusal to join the military coalition against Assyria but was the fruit of centuries-long hostility between “Israel” and “Judah.” Bad blood flowed between the kingdoms and occasionally erupted into violent confrontations.

(Photo: Reuters/Shir Torem)

The root of today’s crisis, seemingly, does not stem only from the implementation or lack of official implementation of the ‘judicial reform,’ but rather is the fruit of longstanding anger, humiliation, fear, hatred and vengeance between the two tribes in Israel.

One side screams about the jarring ethnic gaps in education, wages, politics, in the halls of the court, and in leading the economy, while the other side recalls the blood, sweat and tears that their forefathers shed when they established the state, and that their descendants are effectively still keeping it.

One side is calling for necessary reforms to preserve Israel as a “Jewish state,” convinced that its democratic component will only be strengthened; the other side laughs bitterly at this, then becomes somber at the thought that their state is linearly moving toward dictatorship.

Who is right? And can one even logically decide on ethical questions? The chronology of the two kingdoms in the Bible tells us another story. When Israel and Judah cooperated in the days of Jehoram, King of Israel, and Jehoshaphat, King of Judah (who, incidentally, enacted legal reform himself), God assisted them and, through his prophet Elisha, assured them of the defeat of their enemy Moab, which indeed happened. But prophets like Elisha no longer exist today, and no one is truly capable of predicting the end of the intra-Israeli rift.

At this point, perhaps one can only hope, and quote the prophet Isaiah and Ehud Manor. “Ephraim’s jealousy will vanish, and Judah’s enemies will be destroyed; Ephraim will not be jealous of Judah, nor Judah hostile toward Ephraim. May no one hurt and a brother would love his brother, may we’ll open Eden’s gates, knock down the door, may East and West merge and urge each other, may our days will be renewed as once before.”

As reported by Ynetnews