‘Houses of Life’ collects documents and artifacts on 2,000 years of Italian Jews, puts spotlight on renovations underway at Jewish sites

MANTUA — An exhibition at the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (MEIS) in Ferrara has been showcasing the ritual and social features of synagogues and Jewish cemeteries in Italy, tracing 2,000 years of the country’s Jewish history through artifacts, designs and cultural projects.

The display, titled “Houses of Life: Synagogues and Cemeteries in Italy,” is linked to restoration and recovery work carried out by the Jewish Cultural Heritage Foundation (FBCEI) at Jewish sites throughout the country and beyond.

The exhibition, which closes Sunday, allows visitors “to discover the richness of the Jewish cultural heritage in Italy, of which cemeteries and synagogues are a fundamental expression,” said FBCEI and MEIS president Dario Disegni.

“The most important effort promoted by the foundation is the restoration of the Valdirose cemetery, which is located on the border between the adjoining towns of Gorizia and [the now-Slovenian] Nova Gorica; it’s a project we have been working on for years.”

Disegni added that the cemetery’s restoration represents one of the most important projects leading up to 2025, for which Gorizia and Nova Gorica have been jointly selected as that year’s European Capitals of Culture (along with Chemnitz, Germany). The yearlong designation brings with it a series of cultural events — and often a considerable upswing in tourism.

According to Disegni, the initial work on the cemetery has begun and restoration of the tombstones will begin soon. As part of the renovation, an information point will be constructed in what was once the chapel, telling visitors about the cemetery and the lives of some of the illustrious people buried there.

The FBCEI has also initiated the restoration of the extraordinary and seldom-visited Jewish catacombs in the southern Italian town of Venosa.

“We are waiting to release some tranches of funding in order to be able to proceed with the work,” said Disegni, noting that “multiple Italian Jewish communities are engaged in the restoration of synagogues. Projects of this type have been carried out or are currently underway in Ferrara, Turin, Alessandria and Vercelli.”

The restoration of the synagogues in Florence and Siena, which were hit by an earthquake earlier this year, is also of great importance, added Disegni.

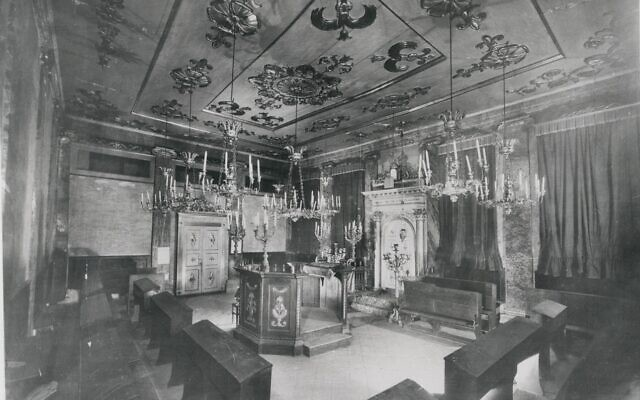

“Houses of Life,” curated by Amedeo Spagnoletto and Andrea Morpurgo, tells the stories of different cities and people via such methods as architectural projects, familiar objects and documents loaned from state archives and Jewish communities. The initiative, which received the Medal of the President of the Republic, is supported by the Italian Ministry of Culture, the Union of Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI) and other organizations.

The exhibition focuses on the relationship between Italian Jews and their rulers in different eras. A journey through time takes visitors to discover the meadows (also called ortacci, burial places intended for Jews) located outside the city walls in the Middle Ages, the Jewish catacombs of Rome and Venosa, and the ancient cemeteries.

Visitors can admire a prayer book for holidays from the 15th century and the Holy Ark of Vercelli that housed the community’s Torah scrolls — which date back to the 17th century and the time of the Italian ghettos — as well as ancient documents pertaining to the construction of new synagogues in some of Italy’s main cities.

Other fascinating objects include the 1722 grave marker of rabbinic master Yehudah Leon Briel — originally from Mantua, one of the most important centers of Italian Jewish cultural life — and a bronze-clad seat formed in 1887 by sculptor Mario Quadrelli for the Jewish section of Milan’s Monumental Cemetery.

A painting by Alessandro Magnasco, considered to be one of the most original painters of the 18th century, stands out among the various pieces of art on display. Depicting a Jewish funeral procession, the painting came to the MEIS via the Museum of the Art and History of Judaism in Paris and makes its permanent home in the Louvre.

Spagnoletto said the exhibition, “Houses of Life,” takes its name from its main subjects: synagogues and cemeteries.

“Synagogues are not just intended for prayer but are real houses of the community,” he said, “while cemeteries in the Jewish world are called batei chayim, or houses of life.”

“These two places, despite their differences, have harbored existences, stories and identities for millennia,” said Spagnoletto. “Unlike private homes, in these spaces self-representation shifts from the individual dimension to the community one and, for this reason, in the Jewish tradition it becomes eternally alive.”

Through the exhibition, visitors will be able to understand the evolution of sacred spaces and the activities that took place within them. Ancient testimonies document the cemeteries, the catacombs and the Roman-era synagogue of Ostia Antica, which was discovered in the 1960s and dates back to the end of the first century CE — as well as the synagogue of Bova Marina in Calabria, dating back to between the third and fourth centuries CE in one of the first signs of Jewish presence in southern Italy.

Spagnoletto said the MEIS takes care to pay attention to initiatives that aim to safeguard Italy’s Jewish cultural history.

“We have included works of art that belong to the Jewish communities of the past, but also various liturgical objects created after World War II, which testify to the vitality of the Jews after the tragedy of the Holocaust,” he said.

As reported by The Times of Israel