The Intouchables’ massive box-office success not only rescued the French actor from a turbulent personal crisis but also transformed his life; Now he stars in The Kitchen Brigade which tackles the refugee crisis in France; Speaking with Ynet, he voices concerns about the resurgence of racism and antisemitism in his homeland, yet he remains optimistic

About 15 years ago, French film star François Cluzet experienced a personal and family crisis that upended his life. Then he received an offer from directors Olivier Nakache and Éric Toledano to star in a movie titled The Intouchables. Based on the true story of Philippe Pozzo di Borgo – a noble French millionaire who became quadriplegic following a paragliding accident – Cluzet was asked to play the lead role.

Pozzo di Borgo developed a unique relationship with Abdel Sellou, his Moroccan-Algerian caregiver. Sellou, who was a petty criminal from the suburbs of Paris, is portrayed in the film as originating from Senegal.

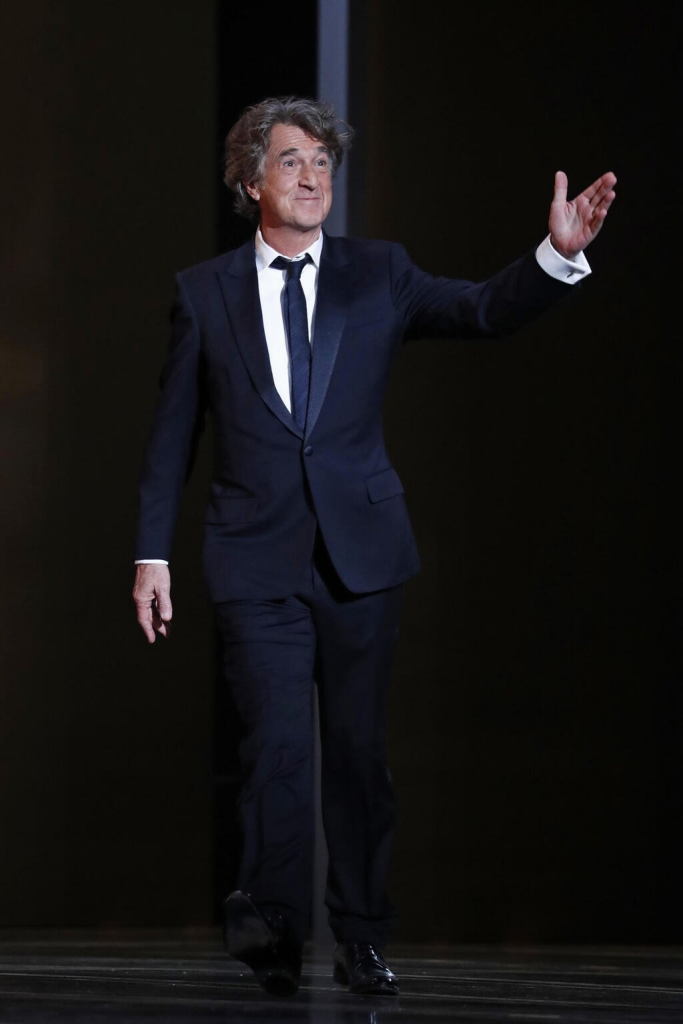

(Photo: Pool/Getty Images)

The film, co-starring Cluzet and Omar Sy, was released in France in the winter of 2011. It broke box office records and became a social phenomenon.

Nineteen million French people flocked to see it, sparking debates and discussions. President Nicolas Sarkozy hosted a celebratory screening at the Élysée Palace.

However, Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the anti-immigrant right-wing party National Front, expressed his disdain and hatred for the film, claiming it was an “offensive metaphor showing how France, represented by the disabled rich man, is exploited thanks to a young black migrant.”

The Intouchables won numerous awards, was sold to 40 countries, and even got a Hollywood remake starring Bryan Cranston.

In Israel too, The Intouchables was a box-office smash, inspiring a play based on the film at the Cameri Theater. The striking success came at just the right time for Cluzet.

“I was fortunate that once in my career, I had a hit of this magnitude,” Cluzet, 67, tells Ynet in an interview via Zoom. “During that period, I was experiencing a personal crisis (likely referring to his separation from his actress wife Valérie Bonneton, mother of two of his four children) and I felt a need for love, especially everyone’s love. And there it was, I received it. Also, I always wanted to be a famous actor – it was my childhood dream, and it came true. The success contributed to my self-confidence.

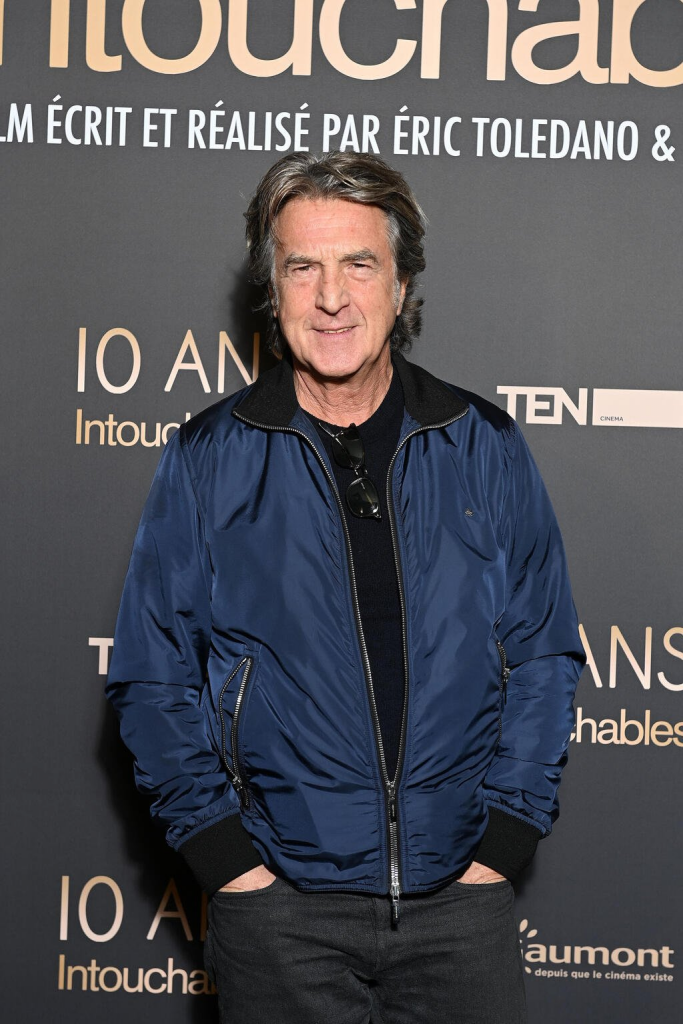

(Photo: Julien M. Hekimian/Getty Images)

My life didn’t start so well. I grew up in a home where I greatly lacked love, attention and affection, and I felt that maybe if I became famous, people would love me. I also dreamed of being loved by a beautiful woman. I am not very tall and not very handsome, so I thought to attract a beautiful woman, I needed to be famous. And it happened.”

What reactions did you receive following The Intouchables? “I toured the world with the film. I was recognized on the streets of Beijing and was offered caviar in Moscow. Everywhere I went, people wanted to take photos with me. Many praised my role, saying it must have been incredibly difficult to stay immobile all the time. But honestly, it wasn’t difficult: you express yourself through your gaze and humor. It was also a privilege to work with Omar Sy – since the story is based on relationships and the laughter between us was genuine, the camaraderie was real.”

Last June, Pozzo di Borgo passed away at the age of 72. “Thank you for all the love you gave us, fly as high as you can, no harm will ever come to you, we will never forget you,” Cluzet announced. “He was a funny man who refused pity. Philippe showed interest in everyone he met, and after two minutes, you no longer took into account that he was in a wheelchair.”

After The Intouchables, Cluzet was flooded with offers. Since then, we’ve seen him in a series of films, including Irreplaceable, which was very popular with the Israeli audience, Back to Burgundy, Naked Normandy and Rose Island (available on Netflix).

Now Cluzet arrives on Israeli screens with The Kitchen Brigade. The plot follows Cathy (played by Audrey Lamy), a butcher working for a famous chef, who cooks much less well than her. Dreaming of opening her own restaurant, Cathy quits her job in anger and struggles to find a new, decent one.

Eventually, she begins working in a shabby cafeteria of a hostel for migrants, including from Africa. The start isn’t easy, but she manages to ignite their passion for cooking.

Cluzet portrays the manager of the hostel where the youths are held until their fate is decided: whether they will be sent back to their countries or gain status in France. The manager works to make their time enjoyable, gives them language lessons and helps them acquire additional skills, in the hope that these will help them gain legal status. Sometimes, he also absorbs their disappointments.

Gradually, the manager gets drawn to the chef. “I heard that director Louis-Julien Petit has a new script called The Kitchen Brigade and there’s a role for me in it, but he dared not offer it to me because he fears it’s too small for me,” reveals Cluzet. “I decided that I wanted to join the project anyway.”

So why did you agree to take a supporting role? “I agreed because I was familiar with Petit’s work and his previous films, including Invisibles, which are character-driven, dealing with societal and political issues – yet still humorous. Beyond that, I don’t need only leading roles – I want good roles and good films. I told Audrey Lamy, ‘I will support you throughout the film, because in my opinion there are no good actors, only good partners.’ There’s something special and rare about Audrey. She can make you cry for hours, but she also maintains a comedic range.”

(Photo: Stephanie Bradshaw)

In The Kitchen Brigade, Cluzet’s character suffers from a limp, but it wasn’t originally planned. “On the first day of shooting, I arrived on set and the boys were just warming up for a soccer scene. I wasn’t supposed to play soccer, but I suggested to the director that I could pass the ball a few times. It seemed like a great idea. So I kicked the ball once, then again. Then I felt as if someone had hit the back of my leg. Despite this, we continued the scene, and then the director called cut. I went to the physiotherapist who was on set, and he immediately sent me to the hospital. But he also said, ‘If they want to operate on you in the hospital, don’t agree.’

At the hospital, the doctor said I needed immediate surgery. So I told him, ‘No, I need to go back and tell the director that I have to give up the role.’ But it was impossible for me to quit, so the director rewrote the character so I could play it, despite the Achilles injury.”

How was your encounter with the boys in the film, some of whom are immigrants themselves? “These boys won our hearts. Their challenging experiences prompted us to ask questions about the status of people like us – established French citizens. I learned a lot just from watching them play. The boys opened up to us, and we also shared with them some of our own life experiences.”

Issues like immigration, refugees and racism greatly concern Cluzet, as they weigh heavy on the mind of the French, especially following recent riots sparked by the death of a 17-year-old Algerian boy who was shot by a traffic police officer.

“Antisemitism, racism and intolerance are rearing their heads in France now,” Cluzet says. “There is an immigration problem. Immigrants hope to cross the sea, and when they embark on the journey, they know they have a slim chance. Why do they risk it? Because they see we have everything, and they have nothing. We are responsible for globalization, and thus we are also responsible for the fact that all these people have nothing.

When politicians say that immigrants are stealing our jobs, these are meaningless political platitudes. Without immigrants, there would be no one to work in our restaurants or build our homes. What’s happening in the war in Ukraine is also terrible, and we need to accept the refugees coming from there. We need to think about the waves of immigration and the immigrants, and not let them become invisible.”

(Photo: Stephanie Bradshaw)

In another film you’ve made recently, The Man in the Basement, you portray a Holocaust denier and antisemitic conspiracy theorist who, by mistake, is sold a storage area basement by a Jewish couple and moves to live there. This surely wasn’t an easy role for you. “I’ve played negative characters before. It’s interesting for an actor to be able to showcase different sides of themselves, to find the evil within yourself. When you play a monster, you need to find the humanity and complexities in such a character.

Additionally, I wanted to make this film because it deals with a topic as important as antisemitism, which is intensifying in France. A significant portion of immigrants from North Africa are against Israel, and this is leading to an increase in antisemitism. This is something that politicians in France have neglected. They haven’t acted to prevent this wave of antisemitism and racism, and so a situation has been created where the far right is gaining power.

“For years, France was a right-leaning country, but now it has become a country of the far right. Therefore, I’m glad there’s a film that protests against antisemitism and Holocaust denial. All sorts of losers are voicing their odd and peculiar opinions on Facebook, spreading lies to draw attention. It’s become a very serious matter. The state needs to do something to control and stop this phenomenon and raise awareness about it. Just imagine, nowadays many young people in France have never even heard of the Holocaust, how is it possible? Apparently, the history books don’t accurately convey the full drama. And so, you can find crazies saying terrible things, and at any given time, there will be someone who believes them.”

Cluzet is active in several social organizations, including an organization that helps victims of domestic violence, a commitment that arose from the tragedy that struck him and his son, Paul, from his relationship with actress Marie Trintignant. In 2003, Trintignant’s partner, singer Bertrand Cantat, beat her to death – and Cluzet took guardianship of the son.

Cluzet is also involved in an organization that assists immigrants, very much like the one shown in The Kitchen Brigade. “You have to give back. Luck is like a boomerang – if you don’t throw and send it forward, it won’t come back to you. The meaning of life is to give – and giving is what makes you happy. I do understand the French people’s fear of waves of immigrants, but it’s disgusting to say that they come to France just to commit crimes, to steal and to rape. What touches me most is the humiliation they go through – I hate it when people are belittled, especially when they belittle strangers. I don’t know where people’s need to humiliate comes from. I simply can’t understand it.”

(Photo: Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images)

Where did you get your social awareness and sensitivity? “I think it comes from my childhood. My mother wasn’t present – she left home for love and my father suffered from depression. So, when I was 5, my father, brother and I had to move to live with my grandparents in Paris, in a very small two-room apartment on the ground floor. The three of us found ourselves sleeping in the same bed. We received sheets and towels from a social worker. We grew up without love and had to deal with my father’s depression, which in one of his episodes, he tried to hurt us. Because I didn’t receive love then, my desire to be loved by as many people as possible was great. My encounter with theater aroused even more the need for love.”

How did you discover acting? “One evening, I went with my family to see singer Jacques Brel in a production of the musical Man of La Mancha. Brel sang, cried, sweated and my first reaction was, ‘His parents must surely yell at him.’ I reacted this way because we weren’t allowed to express ourselves in my home. But when I saw how the theater-goers stood up and applauded him for 20 minutes, I told myself that I, too, wanted to cry and have so many people applaud me. Throughout my childhood and adolescence, I interviewed myself. I asked ‘what are my dreams, what kind of life will I have.’

When I went to acting school in the 70s, I questioned whether I was talented enough. I always considered myself a bit ugly, not pretty enough, not tall, not short. Unlike some of my friends whose appearance meant they were often cast in stereotypical roles, I relied on other aspects that helped me land interesting projects.

“Also, I knew I was good, and I was fortunate that during this period it wasn’t only the most beautiful actors who succeeded – in America, actors like Robert De Niro, Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino changed the audience’s expectations of a male hero. Meanwhile, in France, Gerard Depardieu was making waves, and thanks to him, audience expectations changed. Suddenly, there was attention to the character he portrayed, not just the form. I received a wide range of roles.”

The journey to the top took time and had its ups and downs. In the 80s, he was nominated for a César Award in the Supporting Actor category for the hit “One Deadly Summer” and the excellent film Round Midnight. In the 90s, he worked with Hollywood directors in Robert Altman’s Prêt-à-Porter and Lawrence Kasdan’s French Kiss. Meanwhile, his behavior and lifestyle caused him numerous complications.

(Photo: Courtesy of Nchshon Films)

“Since I didn’t have a childhood, I tried to live it from age 20 to 40. Although I wanted to succeed, gain recognition and respect, I did stupid things, had drinking problems, and got into fights. I gained a bad reputation as someone difficult to deal with.”

Only at the age of 50 did he finally win a César for his role in Guillaume Canet’s 2006 film Tell No One. Another collaboration with Canet, Little White Lies (2010), also achieved significant box office success. But nothing compared to the effect of The Intouchables.

“It was a very big change for me,” admits Cluzet. “My childhood dream of becoming famous was realized. Until then, producers did not want me. It was always the directors who fought for me. Now the producers are the ones offering me projects. I can tell all those children who suffered, that life will help them and eventually everything will fall into place. Now I can think about all those people who didn’t manage to fulfill their dreams and try to help them do it.”

As reported by Ynetnews