In peer-reviewed study, scientists from Weizmann Institute find 4 common sugar substitutes alter gut bacteria, and say 2 of them may actually harm ability to process glucose

An Israeli scientist says that artificial sweeteners should no longer be assumed safe, after his lab published peer-reviewed research suggesting they may actually increase sugar levels in the body.

Immunologist Prof. Eran Elinav of the Weizmann Institute of Science told The Times of Israel that unless it is proved that his team’s concerns are unfounded, “we should not assume they are safe.”

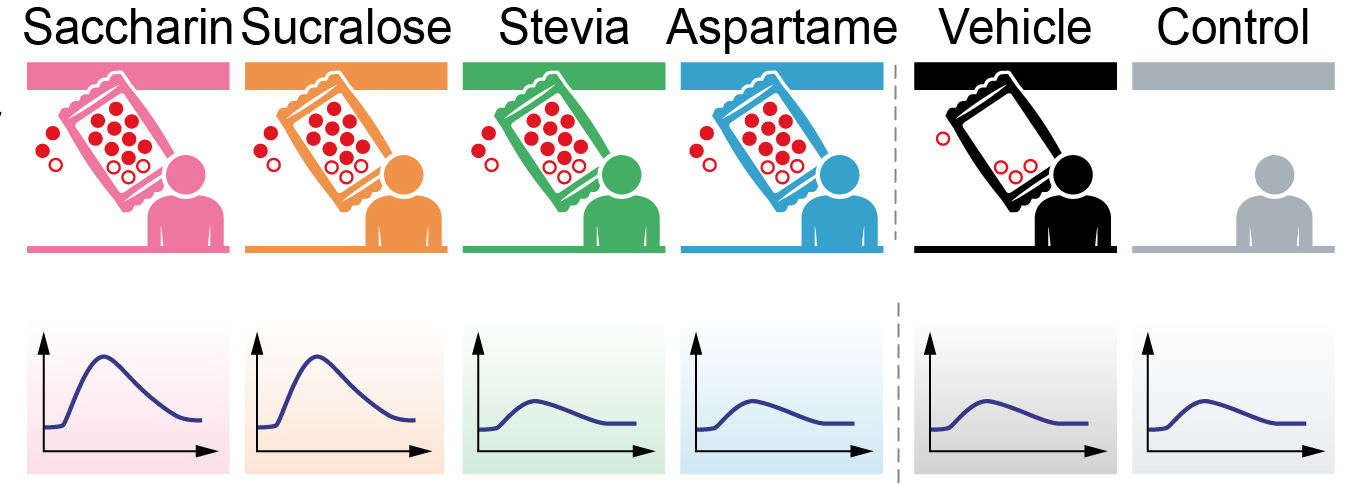

According to the study, published in the journal Cell, consuming saccharin and sucralose harms the ability of healthy adults to dispose of glucose in their body.

It is long-awaited human research from the Israeli team that rang alarm bells about artificial sweeteners eight years ago based on a study with rodents.

The scientists argued at the time that sugar substitutes were introduced to satisfy the sweet tooth with less harm to glucose levels but they “may have directly contributed to enhancing the exact epidemic that they themselves were intended to fight.”

Now, they have broadly corroborated their rodent study by monitoring dozens of adults who normally assiduously avoid artificial sweeteners when they consume them.

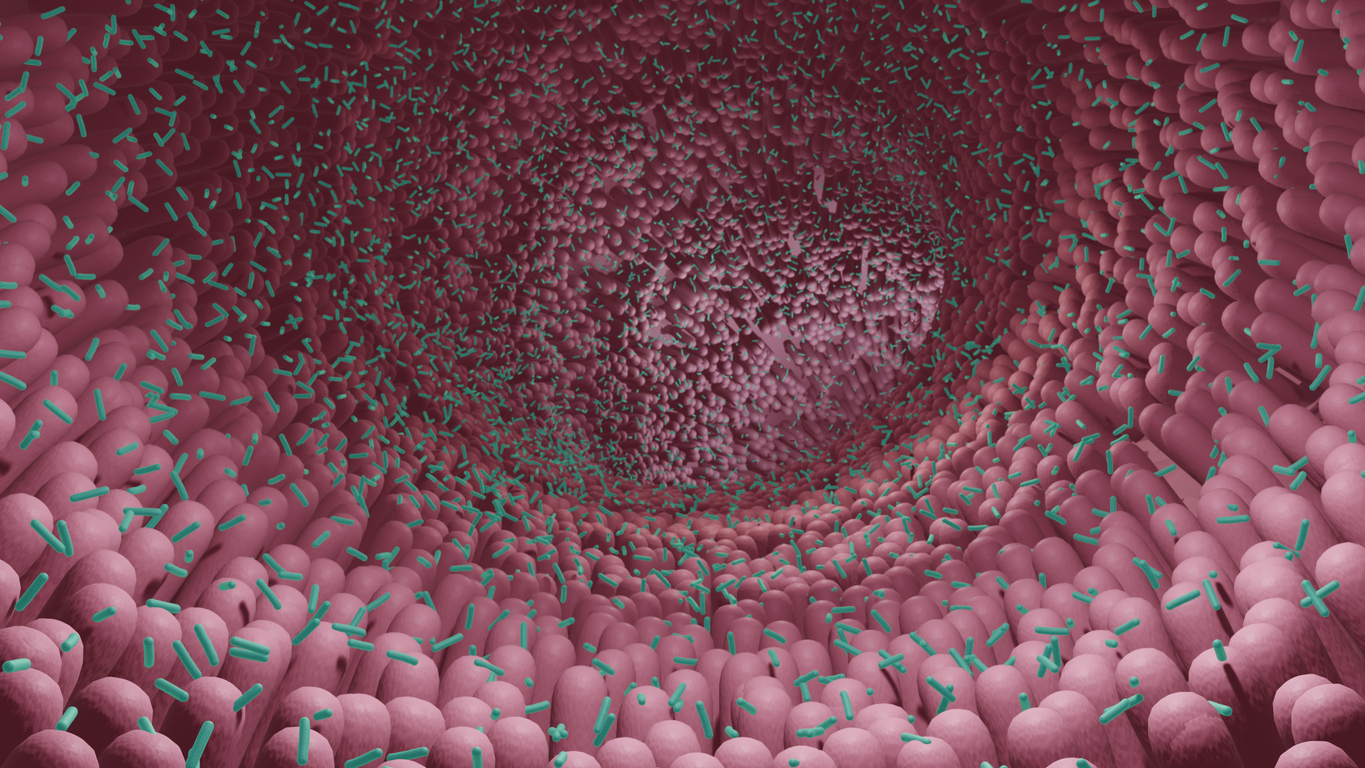

“Our trial has shown that non-nutritive sweeteners may impair glucose responses by altering our microbiome,” said Elinav.

This strongly challenges the common assumption that sweeteners provide a harmless hit of sweetness without any health cost, Elinav added.

The research was led by Dr. Jotham Suez, a former graduate student of Elinav’s and now principal investigator at the John Hopkins University School of Medicine, together with Yotam Cohen, a graduate student in Elinav’s lab, and Weizmann’s Prof. Eran Segal.

The scientists conducted their experiment with the four most common sweeteners: saccharin, sucralose, aspartame, and stevia. The first two appeared to significantly impair glucose response, but all four of them caused changes in the gut bacteria, the microbiome.

Elinav stated: “We found that the gut microbe composition and function changes in response to consumption of all four sweetness, meaning that they are not inert to the human body.”

These changes weren’t detected among other volunteers who were in control groups and therefore didn’t consume sweeteners.

The scientists transplanted feces from some of the people in the experiment into rodents bred to have no gut bacteria of their own. They found that mice with feces from people whose glucose tolerance was hit hardest by sweeteners also had a reduced ability to dispose of glucose.

They say this strengthened their theory that sweeteners are affecting the microbiome, and that the changed microbiome can impact glucose tolerance — so markedly that it has this effect even if transplanted to another species.

“Our current results strongly suggest that artificial sweetness are not inert to the human body or to the gut microbiome, as once thought, and may potentially mediate changes in people, possibly in a highly personalized manner stemming from different people’s unique gut microbe populations,” said Elinav.

“In my opinion as a physician, once it has been noted that non-nutritive sweeteners are not inert to the human body, the burden of proof of demonstrating or refuting their potential impacts on human health is at the responsibility of those promoting their use, and we should not assume they are safe until proven otherwise. Until then, caution is advised,” he said.

As reported by The Times of Israel