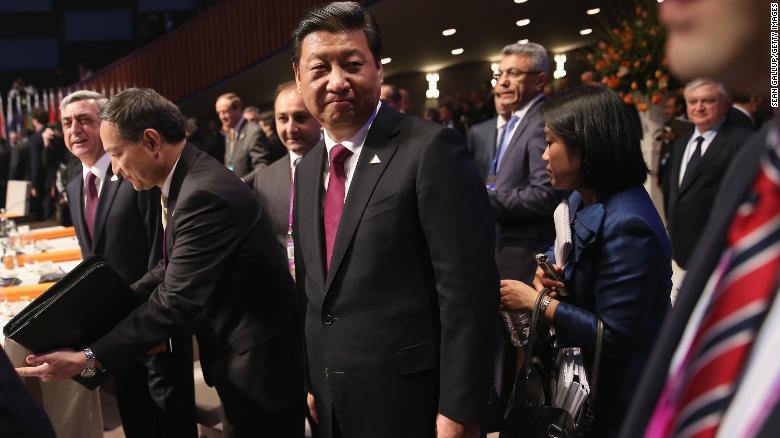

Hong Kong – When Chinese leader Xi Jinping made his first state visit to Europe in 2014, he set out to herald a new era of cooperation in a multi-country tour, which the European Parliament President at the time called “a welcome signal of the importance that the new Chinese leader attaches to a strengthened EU-China partnership.”

Eight years later, the optimism of that period has cratered, with the relationship between China and the European Union reaching what analysts call a clear low point of recent decades.

European concern about China’s global ambitions and its human rights record, US-China tensions, tit-for-tat sanctions and, now, Russia’s war in Ukraine — the impact of which on China-EU ties Beijing appears to have either underestimated or dismissed — have all brought relations to a nadir.

That was underlined last month during two summits featuring European leaders. Both the Group of Seven (G7) advanced economies and NATO significantly hardened their lines on China, in a signal that views in Europe have fallen more in line with Washington’s.

The shift is the culmination of a series of steps in which Beijing may have at times underestimated the extent to which it was pushing Europe away, but also appeared prepared to pay that price.

But it is a significant blow for Beijing’s ideal vision: a Europe with robust China ties that provides a counterbalance to American power and posture.

“China and the EU should act as two major forces upholding world peace, and offset uncertainties in the international landscape,” Xi told EU leaders at a summit in April, urging them to reject “rival-bloc mentality.”

But those words appeared to fall flat with the European side, which focused instead on pressing China to help broker peace in Ukraine. “The dialogue was everything but a dialogue. In any case, it was a dialogue of the deaf,” EU foreign affairs chief Josep Borrell said afterward.

Downward spiral

Beijing had carefully crafted its relationships in Europe in recent decades — creating a dedicated annual summit with Central and Eastern European countries and seeking inroads for its Belt and Road infrastructure initiative, which won support from one G7 member when Italy signed on in 2019.

US concerns about the risks of collaboration with China resonated in Europe. And European nations were themselves watching Xi’s China grow increasingly assertive in its foreign policy, from the combative tone of its “wolf warrior” diplomats to the establishment of a naval base in Africa, rising aggressiveness in the South China Sea and toward Taiwan, and the targeting of companies or countries that ran foul of its line on hot-button issues.

Allegations of major human rights violations in China’s northwestern region of Xinjiang, and its dismantling of civil society in Hong Kong also played a role in shifting European perceptions, analysts say.

Chinese officials have called allegations that it held more than a million Uyghur and other Muslim minorities in internment camps in Xinjiang “fabrications,” and slammed discussion of these issues as “interference” in its internal affairs.

The EU declared China a “systemic rival” in 2019 and ties have continued to fray since.

“China now demands the rest of the world pay it due respect and recognize the positions China takes, without paying much regard to what the others may think,” said Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London.

This approach made Western democracies “abandon the decades-long policy of helping China to modernize and rise with a hope that greater economic integration will encourage China to become a responsible stake holder in world affairs,” Tsang said.

Economic edge

China was the third largest export market for European goods and the largest source of products entering Europe last year, but frictions have taken their toll on the economic relationship between the EU and Beijing.

Earlier this year, a dispute between China and Lithuania pushed the EU to level a case at the WTO. It accused Beijing of “discriminatory trade practices against Lithuania” in retaliation for what Beijing views as a violation by the Baltic state of its “One China” principle, by which it claims self-ruled Taiwan as its sovereign territory.

The greatest financial casualty was the long-awaited trade deal between the EU and China, which stalled last year after being caught in the crossfire of a sanctions exchange. Beijing slapped penalties on EU lawmakers and bodies, European think tanks and independent scholars after the EU sanctioned four Chinese officials for alleged abuses in Xinjiang.

But the damage was greater than just the deal.

“This overreaction (from Beijing) was not a wise move,” said Ingrid d’Hooghe, a senior research associate at the Netherlands-based think tank Clingendael, pointing to the harmful effect on public opinion.

“China’s strategy toward Europe was falling apart and it apparently didn’t understand that all these actions — the over-reactive sanctions, coercive diplomacy — in the end worked against China’s diplomatic goals … and also pushed Europe closer to the United States,” she said.

While these actions may have pushed a shift in European thinking with clear economic consequences, they added up for Beijing’s Foreign Ministry, according to Henry Gao, a professor at Singapore Management University’s Yong Pung How School of Law.

“For them, the cold relationship is a necessary price and it is more important to make political points,” he said.

Blind spot?

It is China’s most recent calculations over how to respond to Russia’s war in Ukraine that may end up the most costly when it comes to European ties.

As European countries and the US united in support of Ukraine, China refused to condemn the war — instead bolstering its relationship with Russia and joining the Kremlin in finger-pointing at the US and NATO.

There were leading policy analysts in China who understood the negative consequences China’s position would have on its European ties, according to Li Mingjiang, an associate professor and Provost’s Chair in International Relations at Nanyang Technological University’s S.

Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. But that assessment may have been “underestimated” by decision makers, Li said.

Calculations about the geopolitical importance of ties with Russia, and also the close bond between Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin also likely came to bear, he added.

“It’s a really huge dilemma for China … and they couldn’t afford any major negative consequences on the China-Russia strategic partnership. That imperative really prevailed,” Li said.

There has been acknowledgment of China’s myopia among mainland scholars,

Chen Dingding, founding director of the Intellisia Institute think tank in Guangzhou, wrote in a coauthored article in The Diplomat, that the risks of the war in Ukraine are “not fully understood in China,” where officials and academics had failed to acknowledge the “shock” that death and destruction in Ukraine would bring Europeans.

“The geographic as well as emotional proximity of the war will fundamentally change European sentiments toward common security, economic dependencies, and national sovereignty for years to come,” Chen and his international group of coauthors wrote.

However, strong voices within many countries do continue to advocate a balanced approach to China, according to d’Hooghe. The future may bring not a decoupling, she said, but rather a recalibration within Europe of how to collaborate with China while keeping an eye on security and balance.

“But right now — and this is also true with the European relationship with Russia — normative considerations seem to weigh heavier than economic interests,” she said.

As reported by CNN