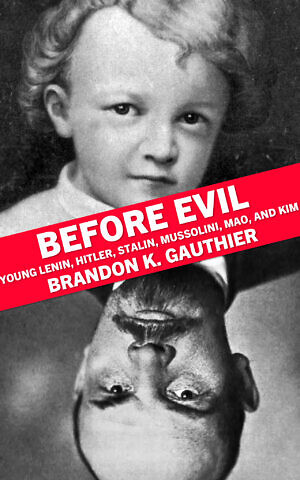

In ‘Before Evil,’ out on April 26, author and historian Brandon Gauthier paints a picture of typical, if somewhat misfit, youths who enjoyed reading and were shy around girls

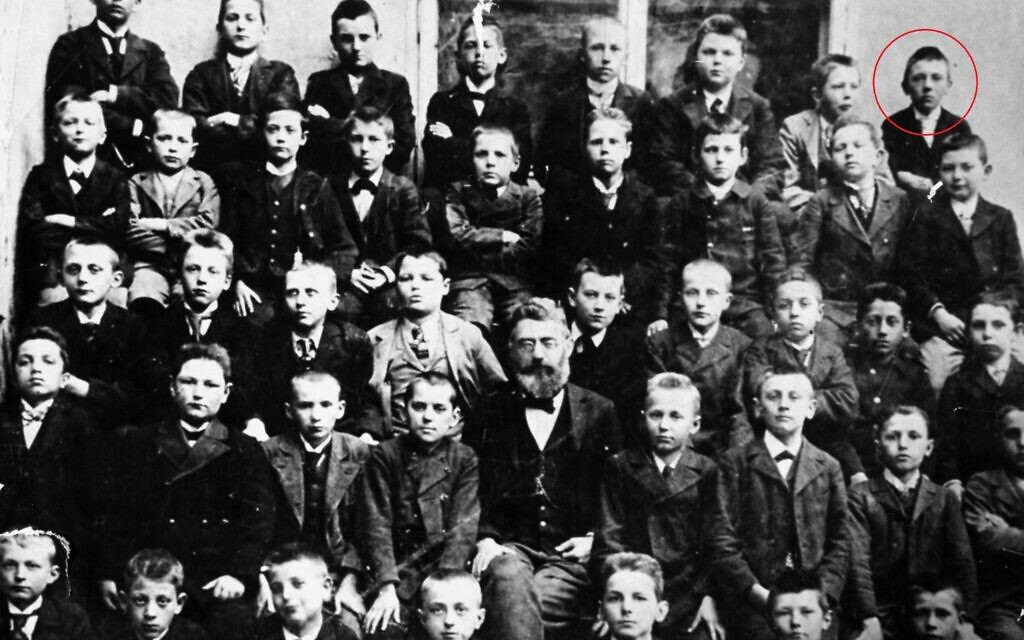

Young Adolf Hitler was more dorky than despotic. He shunned physical activity except for walks and the occasional swim, read Wild West novels and was so shy in love that he never told a young woman named Stefanie about his crush on her.

Does this portrait of a dictator as a young man sound disturbingly normal? A new book by historian Brandon Gauthier asks this question about six of history’s most infamous figures – “Before Evil: Young Lenin, Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, Mao, and Kim.”

In a phone interview, Gauthier told The Times of Israel that he understands that his humanizing approach “is controversial. Part of us only needs to see the monster in the making. What do you have in common with Hitler? It elicits rage.”

As he noted, the sextet’s “crimes against humanity were deeply horrific, some of the very, very worst,” including the Holocaust and Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. He added that his focus on the dictators’ early years was “not [about] providing an exact formula on how they became tyrants, but about shedding light on the humanity of inhumanity — a phrase not heard very often.”

The idea germinated from a 2015 trip to North Korea, when Gauthier — a doctoral student in US-North Korean relations at Fordham University at the time — got a rare opportunity to visit the communist dictatorship. Seeing the bodies of Kim Il-Sung — the final dictator in the book — and his son Kim Jong-Il, he started thinking about the human beings behind the regime, then expanded his list of subjects.

Gauthier focused on the despots’ formative years — a demographic he’s familiar with from his current position as director of global education for The Derryfield School in New Hampshire, where he teaches 14- to 18-year-olds. The book’s April 26 release comes in the wake of two notorious birthday anniversaries: Kim Il-Sung’s on April 15 and Hitler’s on the 20th.

Gauthier made some counterintuitive findings. Although his subjects were linked to atrocities with a cumulative death toll surpassing 90 million, they did not show signs of sadism early in life, such as the youthful torture of animals that marked serial murderers like the BTK Killer.

Instead, the sextet buried themselves in books. Vladimir Lenin devoured Russian novels such as Ivan Turgenev’s “Smoke,” while Benito Mussolini absorbed the plight of the destitute in Victor Hugo’s “Les Miserables.” Some wished to emulate heroic figures from national literature: Joseph Stalin adopted the nom de guerre Koba after the protagonist of Alexander Kazbegi’s novel “The Patricide,” while Mao was inspired by the depiction of Chinese emperor Song Jiang in Shi Nai’an’s novel “Water Margin.”

Gauthier cited a similar account of another future dictator — teenage Vladimir Putin reading the Cold War spy novel-turned-hit-movie, “The Shield and the Sword,” then walking into KGB headquarters to ask for a job; his future employer politely turned him down.

He calls Putin’s young adulthood “a striking example of similar parallels.”

“It is not the story of a mass murderer in the making,” said Gauthier. Instead, he explained, “you see his parents were not bad people, they were doting, caring. When Putin was a university student, his mom gave him a car (a rare luxury) after she won it in a lottery. Rather than selling the vehicle so the family could move into a nicer apartment, the Putins preferred their son to have it.”

“I’ve been thinking a lot the last six weeks,” Gauthier said. “I regret not having a seventh dictator as part of the story.”

Popular history of populists’ pasts

Although the book is grounded in scholarly research, Gauthier eschewed the academic tone of bestselling biographies of Hitler by Ian Kershaw or Stalin by Stephen Kotkin, employing a more informal approach to enhance accessibility. He refers to the young protagonists by the names they used for each other: Lenin and his older brother Alexander Ulyanov become “Volodia” and “Sasha” in a narrative that Gauthier finds illustrative.

Born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, young Lenin was a straight-A student who enjoyed trips to his father Ilya Ulyanov’s dacha, or summer cabin. After Ilya’s death in 1886, however, Sasha joined a plot to kill Tsar Alexander III, but was caught and executed the next year. Lenin, who had previously shown no interest in the revolutionary movements sweeping Russia, now devoted himself to his slain brother’s cause.

“[Lenin] was not going to be a revolutionary,” Gauthier said. “It was Sasha’s hanging that changed everything. He believed his brother must have felt that what he was doing was right, that he could not have acted in any other way. If that’s the case, I have to understand the path the future dictator went down, the influence of ideas that inspired him to become Lenin.”

Overall, he said, the six dictators became who they were through a toxic combination of factors that did not necessarily include trauma, although Hitler, Stalin and Mao each had abusive fathers. Rather, the biggest influence on their early lives was “ideas born of good education, exposure to books, exposure to the influence of intellectuals from a young age.”

Later in life, this helped them embrace ideologies such as communism and fascism, with little regard for the ensuing carnage. Although young Volodia mourned his brother, the adult Lenin did not empathize with the victims of the Russian Revolution.

Similarly, the teenage Hitler cared for his mother when she was dying of breast cancer and appreciated her Jewish doctor, Eduard Bloch. Decades later, in 1941, the doctor received permission to emigrate from the Third Reich. Yet Bloch is quoted saying how rare this was for a Jew in Nazi Germany.

Gauthier recalled a professor asking him: “Brandon, who cares about the fact Hitler loved his mother, that he had moments of empathy before the specter of the Holocaust? Should we not be speaking of the victims of the Holocaust rather than young Hitler?”

“I thought about it a lot while writing the book,” Gauthier said. “If we seek to prevent crimes against humanity because we care so deeply about the suffering of the victims… we have to return to the roots and find human beings in the story, look for some explanation for evil.”

“We never definitively understand what we see at the core,” he added.

What can we gain by mining dictators’ childhoods?

Fellow scholars have varying reactions to this approach.

“It depends in terms of methodology, not only empathy but [attempts at] making some sense, finding patterns, or otherwise potentially bring understanding,” said Thomas Pegelow Kaplan, the director of the Center for Judaic, Holocaust, and Peace Studies at Appalachian State University.

Kaplan wondered how “the [book’s] language [would] be conveyed to readers, who could potentially misunderstand the notion to portray dictators like Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini — and many people would rush to add Putin. There are all kinds of problems and downfalls, the intimation of evil to be understood.”

Florent Brayard, a Holocaust historian at the Paris-based Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales who was part of a 17-person team translating a new edition of Mein Kampf, questioned how much can be gleaned from Hitler’s younger days, such as his struggles as an artist.

“From that period, we cannot draw any conclusions at all about who he will become later, even less with the political leader status he will become after 1933,” Brayard said.

Ironically, Hitler viewed his younger years as important enough to need embellishment. In Mein Kampf, he claimed that he confronted an Orthodox Jew in pre-WWI Linz.

Brayard called this very graphic, but false: “Historians have shown his antisemitism emerged after the war, the First World War, in 1918, 1919, not before… It was not an antisemitism which was embedded in family tradition or his early personality.”

“Most biographies of Hitler acknowledge he was grateful to the Jewish doctor who took care of his mother,” noted Eric Kurlander, a professor of history at Stetson University and the author of “Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich.”

“There are all sorts of odd, contradictory things that need to be explored. I don’t know if it’s humanizing. Recognizing the complexity, the historical, psychological, sociological complexity of dictators’ childhoods is not that unusual and not problematic,” Kurlander said.

“Many biographies of Stalin, Mao, Castro have ‘humanized’ or looked at the complexity of these individuals before they did evil,” he said. “There are obvious reasons why it’s dangerous to do so if you don’t do it responsibly.”

Conversely, he noted a “benefit of humanizing” — it “shows people [that] anyone, people who are very similar to people you may know, could become dictators, or people perpetrating, carrying out evil deeds.”

For Gauthier, this point was driven home after learning about young Mussolini’s reading habits.

“I relate to Mussolini falling in love with Victor Hugo,” Gauthier recalled. “I took the time to go back and read ‘Les Miserables.’ It was phenomenal.” He imagined Mussolini’s father instilling its message to help the poor: “His dad said, you have an obligation to make things right, an obligation to do something… I thought about the impact of such words on a young person.”

He reflected, “Is the message not to let teenagers read Victor Hugo? No. Hugo’s work has often inspired young people to want to make the world a better place.” Yet he’s troubled by a lingering question: “How could it go terribly, terribly wrong, then?”

As reported by The Times of Israel