Out on Apple TV+ October 15, ‘The Velvet Underground’ dives into the countercultural phenomenon started by gay Jewish musician Lou Reed and rocketed to fame by Andy Warhol

NEW YORK — I’m all about subjectivity when assessing art, but there are some things you just have to lay down as fact. One such example is this: The Velvet Underground is the coolest rock band there ever was. Maybe some Israeli tech startup can devise a gizmo that can scientifically prove this statement to be true, but until that day comes you’ll simply have to accept what I say.

The case has been abundantly clear since the mid-1960s, and if you haven’t been paying attention, there’s a spectacular new documentary from director Todd Haynes eager to show you the light — interestingly called “The Velvet Underground,” and out on October 15 on Apple TV+.

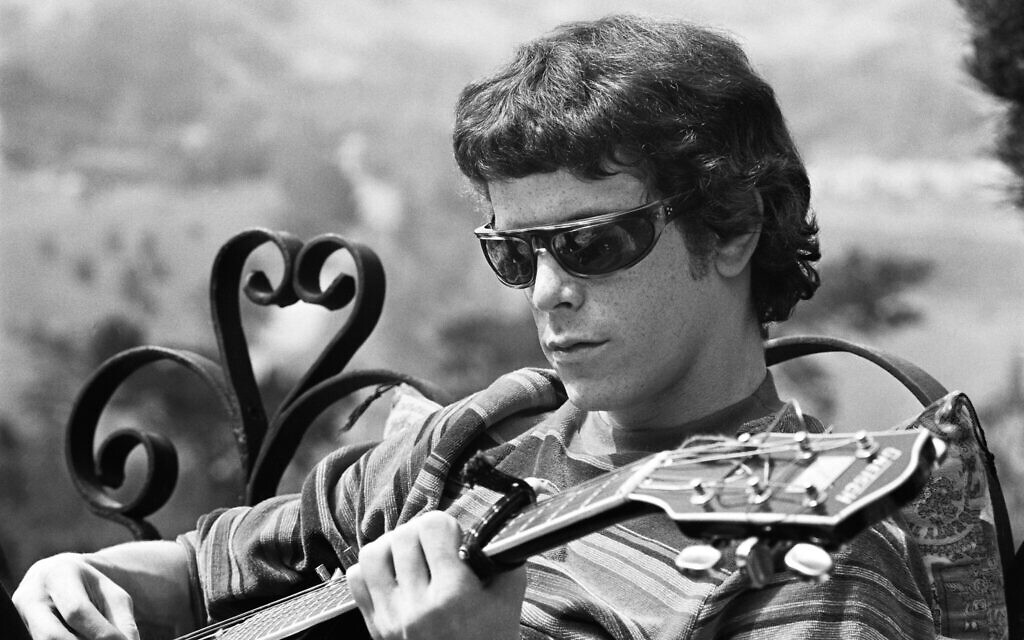

Now, let’s be clear: they aren’t the best band. The singer had a range of about three notes, the musicianship wasn’t particularly nuanced, and while the lyrics were certainly transgressive, they drew their power from blunt force more than wit. But the group, led by the late Lou Reed (born Lewis Allan Reed, originally Rabinowitz) was not just an example of “right place, right time,” they helped create the place and time.

The place was New York City and the time was the ’60s just before they became “the ’60s.” The key players were Reed, a miserable suburban kid whose Jewish parents attempted to have the “homosexual tendencies” zapped out of him via electroshock treatment. (Reed’s sister, in a current interview, doesn’t exactly stand by that decision, but does defend her parents a bit with some “it was the times” prevarication.) Reed quit Long Island for Manhattan with the hopes of becoming a rock star, and ended up working as a songwriter for a discount record company, scratching out “sound-a-likes” and curiosities like “The Ostrich.” But inside was a dark poet yearning to get out.

Luckily he met John Cale, a young Welsh musician schooled in classical music who fell in with an extremely avant-garde circle upon coming to Manhattan. Living in a now-legendary tenement building on the Lower East Side filled with filmmakers and artists and radical thinkers, Cale began experimenting with drones, atonality, sonic textures, and an expansive use of time. Haynes shows how these two men, plus an additional guitarist named Sterling Morrison and a drummer named Maureen Tucker, married Cale’s extreme radicalism with Reed’s rock ’n roll attitude and proclivity toward darkness.

But a key component was missing. It came via the underground Jewish film artist Barbara Rubin, who made a very nice match between the band and Andy Warhol. Warhol was already a pop art sensation who had branched into movie-making, but he soon recognized a musical outlet would fit nicely in his world. The Velvet Underground would become, if I may boil this down a bit, his scene’s house band, performing at multimedia events that mixed music, film, art, fashion, celebrity, crazy lighting, psychotropic drugs, weird haircuts, and everything else we associate with the zeitgeist.

The documentary’s director Todd Haynes (who is Jewish) is known for his craftily designed narrative films like “Far From Heaven,” “Carol,” and (appropriate for rock n’ roll) the Dylan-Iggy Pop-Oscar Wilde-inspired “Velvet Goldmine” and the not-quite-Bob-Dylan-biopic “I’m Not There.” He dives into the Warhol “Factory” archive with great artistry, recontextualizing images many of which we’ve seen before, and in places as boring as public television. Aside from using Warhol-esque split-screens, Haynes fashions the footage to play up the idea that rebellion at this time meant great personal risk. Hanging out in a gay bar could mean economic ruination to people in the straight world, but here was an alternative that stood in defiance of any such anonymity. And with the Velvets’ aggressive music on the soundtrack, the palpable rebellion is energetic.

The film follows the Velvets’ recording years, including their 1967 “The Velvet Underground & Nico” (with the famous banana peel on the cover) and the amphetamine-inspired “White Light/White Heat” follow-up. Reed clashed with Warhol, and then with Cale, and eventually retooled the group in a slightly more user-friendly version. (The few V.U. songs that get played on the radio, like “Pale Blue Eyes” and “Sweet Jane,” come from this later era.) Eventually, Reed left the band altogether, and though there is a longer story to tell, that’s where the movie leaves off.

Though Reed and others both in archival and new interview footage in the film are Jewish, there’s not a single reference made to this fact. I can’t imagine that it never came up at the time — especially when Warhol paired the Velvet Underground with the tall, blonde, German chanteuse Nico — but for whatever reason it is left undiscussed. I mean, when you are as cool as the Velvet Underground, you are too cool for labels of any kind, but it’s weird to me that a total newcomer might watch this documentary and leave unaware of Reed’s ethnic identity. (Though far from religious, Reed later did write songs with Jewish themes and visited Israel.) On the one hand, it would’ve been cool to let people know he was a member of the tribe. On the other hand, the film is honest, and shows him at times being an egotistical jerk and a bit of a lowlife. Maybe best not to advertise too loudly after all?

One thing we are left with, however, is a sense of how a transformative art movement like this is unlikely to happen again in a similar way. As Factory visitor and current critic Amy Taubin points out, one of the key materials used was “time.” In a world where attention spans rarely last longer than a tweet, and technology has made interaction virtual, one mourns for the days of “just hanging out.” Perhaps this documentary’s slick footage — all those cool haircuts, mesmerizing drones, and abrasive lyrics — will, if nothing else, inspire a few kids to stop playing video games and go make some art.

As reported by The Times of Israel