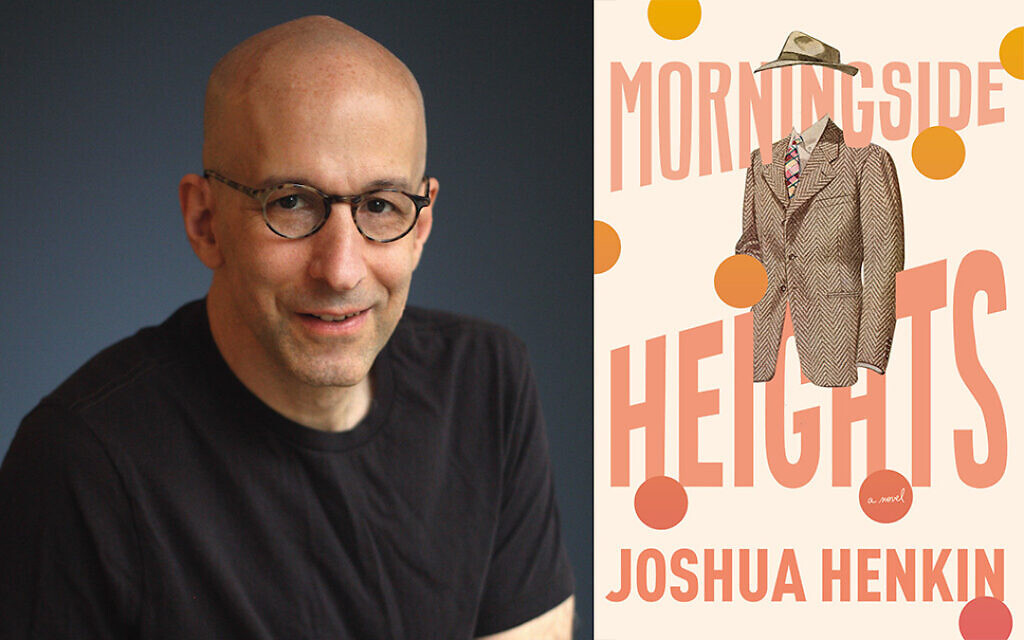

Joshua Henkin’s ‘Morningside Heights’ examines devastating emotional and physical ripple effects after a person loses ability to think, communicate and function before age of 65

In award-winning author Joshua Henkin‘s new novel, “Morningside Heights,” brilliant Shakespeare scholar and Columbia University Prof. Spence Robin mysteriously begins losing his concentration and memory. In a relatively short time, he must give up his writing and teaching.

A shell of his former self, Spence is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Shockingly, he is only in his late 50s, representing the 9% of dementia cases worldwide that are defined as “young-onset,” or occurring in individuals under the age of 65.

“Morningside Heights”— its title taken from the Upper Manhattan neighborhood where Columbia University is located — is a sensitively written tale of the toll that Spence’s dementia takes on his marriage and family.

“It’s about how what happens to Spence has an impact on those who love him,” Henkin told The Times of Israel.

“The challenge of writing a novel about [fatal] Alzheimer’s is that, at least as things stand medically, there’s no tension in what’s going to happen to the character with the disease. The tension has to come from what the characters who don’t have Alzheimer’s do — the characters who know and love Spence and how they accommodate to (and in some cases don’t accommodate to) his illness,” he said.

In an email interview with The Times of Israel from his home in Brooklyn, New York, Henkin, 57, noted that the novel was inspired by his own father’s dementia. Henkin’s father, who was professor at Columbia Law School for nearly 50 years, became ill in his 80s, and was able to continue teaching for several years before dying at age 93 in 2010.

The author said that since advanced scans were not available at the time, and an autopsy was not performed, it was assumed that his father had either Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia, which are the two most common types of dementia. (Alzheimer’s accounts for 60-70% of the the 50,000 million cases of dementia worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.)

The idea for writing about how the dementia of one family member affects the others came from Henkin’s observing his mother sign up for a program for caregivers of dementia patients at a Jewish community center.

“I found [it] really poignant… My mother is not a consorting-with-strangers kind of person, and it suggested how bad things had gotten that she’d go to a class like that for help,” the author said.

When an elderly person shows signs of dementia, the syndrome is often quickly recognized by medical experts. But a diagnosis may be less clear when middle-aged people such as the novel’s Spence — or even younger individuals — have deterioration in memory, thinking, behavior and the ability to perform everyday activities

For example, when Susan Levin’s husband John started exhibiting symptoms of dementia 11 years ago at age 50, she did not understand what was happening and had a hard time finding doctors, especially in Israel, who could help.

“When you are so young, it’s not on the horizon,” Levin said. “It takes so friggin’ long to get a diagnosis for a disease you are ‘too young’ to have.”

Levin, 61, and her husband immigrated with their three children to Israel from Potomac, Maryland, in 2006. They settled in Neve Daniel, in the Etzion Bloc outside Jerusalem, and she opened a craft brewery and worked in the nonprofit field.

John was an international tax lawyer, working for one of the largest accounting firms in Israel.

A “professional’s professional” according to his wife, John was suddenly fired from his job after only a few years for failing to complete his work. Oddly, he didn’t seem to care.

Susan and the rest of the family noticed major changes in John’s personality, including a lack of concern for others. It didn’t seem to bother him that he was unemployed, and he could not be bothered to follow through on filling out paperwork for benefits or showing up at the unemployment office.

Doctors initially consulted said it was just depression, and that it would improve with treatment. But it didn’t. It only got worse, and John started also exhibiting a great deal of anger and frustration.

Two years after being fired, John was finally diagnosed with behavioral-variant frontotemporal lobe dementia (bvFTD). Most people with this type of dementia start showing symptoms in their 50s.

In “Morningside Heights,” Henkin portrays the loneliness and loss that Spence’s wife Pru and children Sarah and Arlo feel as he slips away from them. With Sarah in medical school and oft-estranged Arlo building a successful biotech career, the primary burden of Spence’s care falls on Pru.

Spence had lived a rather ascetic life and Pru has only a few friends, so she has no community to fall back on for support. Ultimately, Spence’s caretaker Ginny becomes her closest ally. However, it is a relationship sometimes fraught with tensions due to differences in class and race, as well as the fact that Ginny comes to know Spence’s routines and needs better than does his own wife.

Susan Levin, fortunately, has a supportive community in Neve Daniel, and around the country within various young-onset dementia (YOD) groups, including ones she helped start. Having initially struggled to get a diagnosis for her husband and put together a care team for him, she now serves as a resource for other families in need of help.

“I am my husband’s caregiver, but I have a team,” she said.

This team includes a male live-in foreign care worker (the current one has been with them for two years), a day program where John goes twice a week for 3.5 hours each time, a medical team available 24/7 headed by a geriatrician, and a family social worker specializing in YOD.

Having outlived a prognosis of four to seven years, John’s condition has deteriorated to the point where he has aphasia — a severe communication disorder (he can no longer communicate through speech).

“His cognitive decline has been massive,” Levin said.

Although John can still walk (though increasingly unsteadily) and even shoot basketball hoops, he can’t dress himself and hasn’t been able to take care of his personal care for years.

In the novel, Spence goes through a similar decline, with physical changes even more pronounced. Like Levin, Pru decides to keep her husband at home and stay married to him. Pru’s fidelity to Spence is tested when she meets a man who can empathize with her situation from first-hand experience with an ill wife.

The emotional struggle and physical exhaustion that come with losing your life partner while he is still alive and and by your side comes through on the pages of “Morningside Heights” and in Levin’s words.

“The person whom you knew intimately no longer exists, but that body is still there and now requires care that you didn’t know would be part of your marriage,” Levin said.

The conclusion of “Morningside Heights” is foreseen from the moment of Spence’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Pru has no illusion as to how it will all end.

“Complications of Alzheimer’s. That was what the obituary said. How she hated that term. There were no complications. It wasn’t complicated at all,” Henkin writes.

Having put her true professional aspirations aside in order to support her husband’s, the fictional Pru is left to figure out a way forward after Spence dies. But at least there is resolution.

Levin and her children and grandchildren are still in limbo.

“I lost my husband and my kids lost their father, but we haven’t had the benefit of a funeral,” Levin said.

“Jewish tradition has structure and markers for loss to help people move on. But there is no such help for our mourning. We are stuck,” she said.

As reported by The Times of Israel