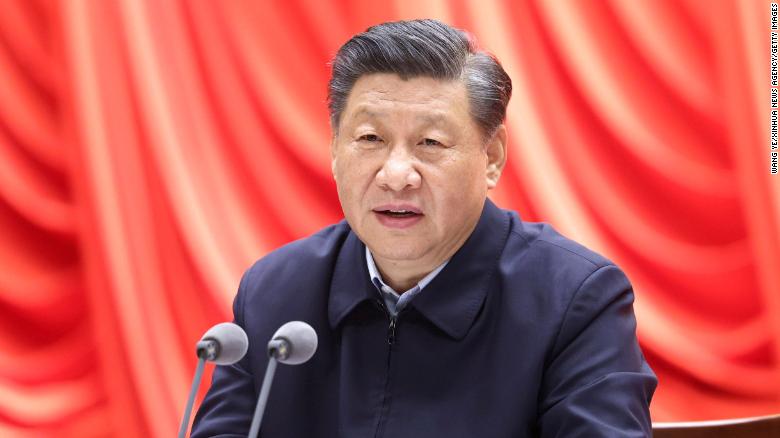

In March 2020, the annual meeting of China’s national legislature in Beijing was delayed for the first time in decades, as Chinese President Xi Jinping attempted to gain control over what would fast become a global pandemic.

One year on, the high-profile event is due to start on Friday, in line with pre-pandemic traditions, in an atmosphere of triumph for the Chinese Communist Party and Xi, who has emerged from the crisis more powerful than ever.

The coronavirus has mostly been brought under control inside China’s borders, while the country’s economy has rapidly rebounded from the damage dealt by the pandemic. China is expected to overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy in 2028, five years earlier than previously estimated.

Xi’s success in handling the pandemic has demonstrated to the Party and any remaining critics that “even the pandemic couldn’t affect him,” said Steven Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute.

Now Xi is working to cement his place in the pantheon of Chinese leaders ahead of the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party’s founding in July, experts said, looking to place himself alongside the founder of the People’s Republic of China — Mao Zedong.

Xi’s initial 10-year term as general secretary of the Party ends in November 2022. But at a time in China’s political calendar when a clear successor would usually be expected to emerge, Tsang said there is only one likely candidate for the Communist Party’s top job.

“We know exactly who the successor to Xi Jinping is, it’s even clearer than ever,” said Tsang. “Xi Jinping.”

Xi triumphant

Traditionally, every March the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) gather for a dual meeting to pass or endorse legislation, known colloquially as the Two Sessions.

The meeting this year will approve the 14th Five-Year Plan, the vast blueprint that will lay out administrative priorities for China until 2025 and cover everything from economic development, to climate change and technological research.

But this year the Two Sessions will also discuss a vision for China’s development by 2035, an unusually long-sighted plan for which the details are mostly unknown.

This long-term plan could indicate the length of time Xi sees himself staying in power, said Bill Bishop, China politics expert and author of the Sinocism newsletter. It is just one way experts see Xi tightening his grip in the wake of China’s successful handling of the pandemic.

Last November, the Chinese Communist Party announced it had reached its goal of eliminating “absolute poverty” in China, fulfilling a promise made by Xi in a speech in 2015.

At a huge ceremony held to honor the achievement on February 25, in a speech, Xi praised his own vision to look at the issue of “real poverty.”

In recent months, Chinese state-run media has elevated its praise for Xi’s role in ending absolute poverty. On February 23, in a full-page article in Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily, Xi was lauded at length. “General Secretary Xi Jinping’s eyes always pay attention to the people,” the article said.

Just days before the Two Sessions was due to begin, People’s Daily published another long piece praising Xi’s involvement in the 14th Five Year plan, describing him as having “the broad vision and extraordinary courage of a Marxist politician and strategist.”

Fordham Law School professor Carl Minzner pointed out in a series of tweets posted to his official account on March 3 that the way in which some Chinese state media outlets were writing about Xi was beginning to change.

“In these articles, Xi is the focus. He is the one that is making things happen. It isn’t about the Party. It isn’t about institutions.

It isn’t about other leaders. It’s about him,” Minzner said.

At the same time, ahead of the Communist Party’s 100th anniversary, Beijing in February launched a “Party History Study Campaign.” In a commentary, state news agency Xinhua said it was necessary to “unify members’ thought, and boost their morale.”

But Bishop said the campaign would also reinforce Xi’s place in the history of the Communist Party, dividing the past 70 years of Party-rule into three eras — Mao’s, Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s and now Xi’s.

“I don’t think we’re going to see erasure of Deng or Mao but certainly an attempt to elevate Xi into at least Mao’s level,” he said.

Succession

Nothing shows Xi’s grip of power quite as strongly as the lack of a successor in the wings.

Since 2002, the tradition has been for Chinese leaders to serve two five-year terms in power and then hand the reins to a new general secretary, chosen by the rival factions within the ruling Communist Party.

But in 2018, the government removed constitutional term limits on the position of China’s president, effectively allowing Xi to rule for life, if he chose. Xi also heads the Party and the military, two posts which are both more powerful than the presidency with no term limits.

The official explanation for the constitutional move has been to align the three positions.

Now with less than 18 months until the 2022 Party Congress, at which Xi would be expected to relinquish power if he were to stick to recent practice, there is no likely successor in sight. In the seven-person Politburo Standing Committee, where the next general secretary would usually be found, all of the leaders are considered too old to serve for another 10 years before hitting the informal retirement age of 68.

All experts agree that the message is clear — Xi is almost certainly planning to serve another term.

“Unless something extraordinary happens that we can’t foresee, like some enormous disaster struck or Xi dies or something, he will have his third term,” said Tsang.

But there isn’t even clear agreement on who might be in line for other major political posts, including a successor for Premier Li Keqiang, who is likely to retire in November 2022.

Bishop said Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, which he put in place as one of the first major policies after taking power, had effectively wiped out a generation of potential leadership contenders.

Xi has also choked off the ambitions for future leaders simply by refusing to name a successor, according to Richard McGregor, senior fellow at Sydney’s Lowy Institute and author of “Xi Jinping: The Backlash.”

But that might change. McGregor said with a third term for Xi now likely, the question was moving to whether or not he would appoint a possible successor at the 20th Party Congress in November 2022, to potentially take over in 2027.

If there is another congress without a potential successor to Xi, McGregor said it could indicate plans for the Chinese leader to serve for a fourth term or longer.

“China’s ability to have peaceful transfers of power has been one of the Party’s greatest achievements and I don’t see how that’s a good idea to throw that out the window,” McGregor said.

No place for criticism

At the height of the uncertainty around the Covid-19 pandemic in China, experts began to mull whether this might be Xi’s “Chernobyl moment” — referring to the 1986 nuclear disaster some believe helped spark the end of the Soviet Union.

For a moment, Xi’s grip on power seemed the most tenuous it had been in years.

But almost as soon as the pandemic began to abate in China, Xi moved to silence the critics who had questioned his leadership during the crisis.

In March 2020, Tsinghua University professor and Xi critic Xu Zhangrun was put under investigation and then subsequently fired after writing an essay critical of the Chinese leader.

“The political life of the nation is in a state of collapse and the ethical core of the system has been rendered hollow,” Xu wrote in an essay published in March.

One of Xi’s strongest critics, billionaire Ren Zhiqiang, was sentenced to 18 years in jail in September 2020 on corruption charges. An essay published in March that year which was widely attributed to Ren referred obliquely to Xi as a power-hungry “clown.”

The message from the Chinese leader was clear — he would brook no more vocal dissent. McGregor said critics of Xi still remain in the political elite but, with his tight control over the media and academia there was no way for them to make their influence felt.

And with Xi headed for a third term in power, that is unlikely to change. “It’s get with the program or else,” said McGregor.

As reported by CNN