The dead nun’s slippers were scattered on the convent kitchen floor — one near the entrance, the other by the fridge.

The dead nun’s slippers were scattered on the convent kitchen floor — one near the entrance, the other by the fridge.

Her white veil was found snagged on the door. An open bottle of water was leaking onto the tiles.

In the corner of the room was an ax.

Officers discovered the crime scene, described in court documents seen by CNN, at St. Pius X Convent Hostel in southern India on March 27, 1992.

Later that day, they found Sister Abhaya’s body in a nearby well at the Indian convent, in the city of Kottayam, Kerala.

A post-mortem examination revealed she had nail marks on both sides of her neck and two lacerated wounds on her head. Her body had multiple abrasions and she had sustained a fracture to her skull.

Despite her wounds and the kitchen crime scene, no one was brought to court over Sister Abhaya’s murder for 27 years. Instead, what followed was years of dead-end investigations, plagued with allegations of corruption.

Finally, last December, guilty verdicts were handed down to a priest and nun who had gone to extraordinary lengths to protect their illicit relationship. The court found Sister Abhaya had walked in on them while they were engaging a sex act in the kitchen, and killed her to conceal their sins. They were sentenced to life in prison.

After nearly three decades of fighting for justice, her family have one overriding question.

“Why did it take so long?” asks Sister Abhaya’s brother, Biju Thomas.

Failed investigations

When she died, Sister Abhaya was a student at a local college run by the Knanaya Catholic Church in Kottayam, then home to about 1.8 million people.

Among India’s Hindu-majority population, 2.3% follow Christianity — a figure that hasn’t changed in more than two decades. But Kerala has a sizable Christian community, around 18% of its people.

According to India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which prosecuted the case, Sister Abhaya woke up at about 4:15am on the day of her murder to study for an exam.

She went to the ground floor kitchen to fetch some water and it was there prosecutors said she found Father Thomas Kottoor and Sister Sephy performing a sex act. Father Kottoor taught psychology at the school and Sister Sephy was in charge of the convent hostel where the act took place.

Prosecutors said the pair “maintained an illicit relationship”.

The night before the murder, prosecutors said the priest snuck onto the convent grounds and stayed in Sister Sephy’s room, which was on the ground floor of the hostel, near the kitchen.

When they realized the young nun had seen them in a compromising position, the pair hit her on the back of the head with a small ax kept in the kitchen, then threw her body into a well on the hostel grounds.

The details of what happened that night didn’t come to light until years later, after immense pressure from activists and the young nun’s family.

Her father, in particular, refused to give up.

The first investigation into Sister Abhaya’s death was opened by the Kottayam West Police Crime Branch on the day her body was found. A year later, it concluded the cause of her death was suicide.

But Sister Abhaya’s father, Matthew Thomas, refused to accept their version of events and urged the CBI, the nation’s premier investigation agency, to take over the case.

They picked it up in 1993, but for 12 years did not charge anyone for her death. Instead, between 1993 and 2005, the CBI filed four reports, including three closure petitions, urging the Chief Judicial Magistrate to drop the case.

In their first report, they agreed with Kottayam police that the cause of death was “suicide by drowning.” However, it was not accepted by the Chief Judicial Magistrate, and the case was reopened.

Their second report, published in 1996, was inconclusive — they could not determine if it was suicide or homicide. Investigators once again urged the case to be closed. This was once again rejected.

Their third report, published in 1999, stated it was a homicide but didn’t nominate any suspects. This was rejected as “unsatisfactory” by the Chief Judicial Magistrate.

Yet another report was filed in 2005, reiterating the case was “untraced,” as they could not identify any suspects. And once again, it was rejected by the Chief Judicial Magistrate.

After this, the investigation was transferred from the CBI New Delhi branch to the CBI in the southern city of Cochin in Kerala.

Finally, in 2009, the CBI formally charged Father Kottoor and Sister Sephy with murder, as well as another priest, Father Jose Poothrikkayil, who police said was involved in the killing.

All three denied the charge, as well as allegations of conducting an improper relationship.

They filed a dismissal request to get the case dropped, and it took another nine years before a judge ordered Father Kottoor and Sister Sephy to face trial. Charges against Father Poothrikkayil were dropped due to lack of evidence.

The trial

On August 5, 2019, the trial finally began.

Prosecutors argued that Father Kottoor and Sister Sephy went to remarkable lengths to cover up their relationship and crime.

According to the CBI, Sister Sephy underwent hymenoplasty, a cosmetic fix to restore or reconstruct her hymen, the day before her arrest in 2008, to make it appear that she was still a virgin.

In court, prosecutors accused police officers from the Kottayam West Crime Branch of tampering with evidence and destroying documents crucial to the investigation.

“It is reasonable to suppose that Father Kottoor had at his control the immense resources of the diocese in terms of money and material, and could command the obedience of priests, nuns, and laymen,” the prosecution said.

Prosecutors alleged lead investigators, including the Superintendent and the Deputy Superintendent of the police, were instrumental in the cover up.

The judge agreed with the prosecution’s assertions that early police investigators fabricated and destroyed evidence, including the plastic bottle, Sister Abhaya’s slippers, and her white veil.

He ordered the state’s police head to ensure that “such misdeeds on the part of the police” do not occur in future.

Only one charge was made against an investigating officer, but that was dropped in 2008 after he died.

At least one other lead investigator from the Kottayam West Police Crime Branch, who was accused of fabricating and destroying evidence, also died before the case concluded.

Father Kottoor maintains his innocence.

“I have done no wrong. God is with me,” he told local reporters as he arrived in court on December 23 for the sentencing hearing.

His lawyer said the case relied entirely on circumstantial evidence.

“There is no conclusive evidence,” said Father Kottoor’s lawyer, B. Sivdas. “And there was a delay in the investigation, a delay in finding the accused, there were so many loopholes. The court convicted them because the case became a sensation.”

Suicide or murder?

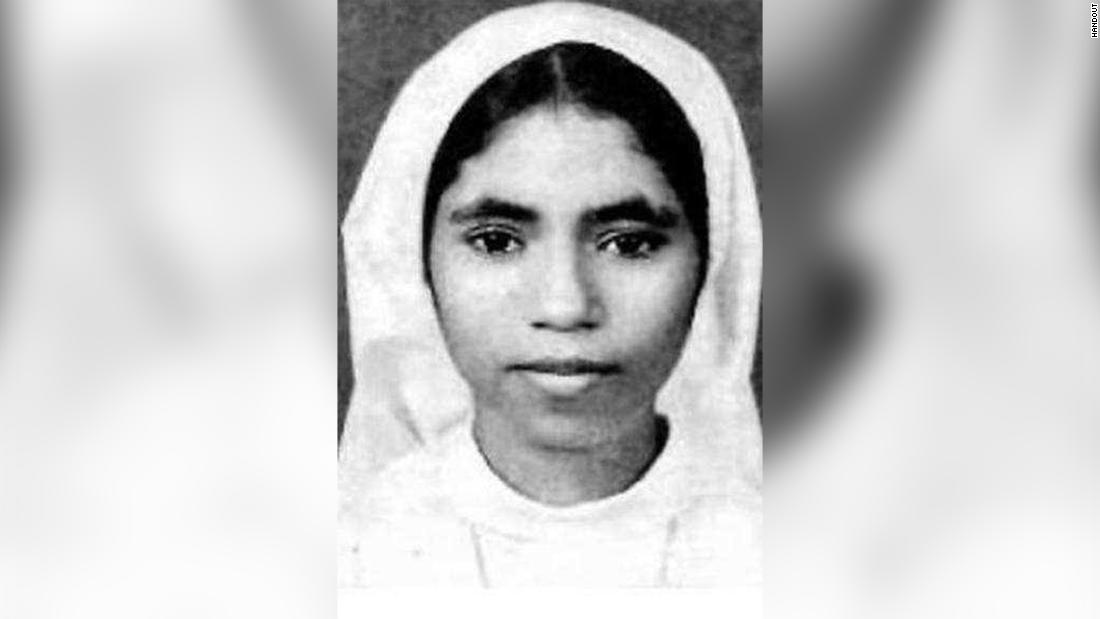

Sister Abhaya — born Beena Thomas — was a “polite and quiet child,” according to her brother, Biju Thomas. They grew up in Kottayam, and were “devout Catholics and followers of Jesus Christ.”

“I remember when she was about five or six, she began taking a huge interest in God and the Bible,” said Thomas, now 51 and living in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates. “She would read the Bible religiously, and take comfort in its teachings. Everyone loved her. She was always laughing.”

Sister Abhaya was 19 when she was “called to a religious life,” according to Thomas. The family had relatives in Germany and Italy who were also nuns. Thomas said that his sister admired the respect they received, and the work that they did.

“She wanted to be respected also, and devote her life to Jesus,” he said.

Thomas was 24 when he was told that his sister had died by suicide. “I was so confused because she was happy, and she was following her dream.

Why would she have killed herself?” he said.

Thomas traveled back to Kottayam town, from the state of Gujarat where he was studying, to be with his family and take care of his sister’s funeral arrangements. Several days later, he visited her body in the morgue and read the postmortem report that revealed his sister had head injuries and nail marks to her neck.

“These to me showed that something had happened to her before she was thrown in the well,” he said.

Sister Sephy filed an eight-page written statement stating that Sister Abhaya suffered from “psychological depression.” She claimed that Sister Abhaya came from an “economically weak family and was not good enough in her studies.”

Some other nuns were “staunch upholders” of the suicide theory, according to the final judgment. They “endeavored to give all support to the accused,” the judgment said.

“It was very hurtful to hear those things said about my sister,” said Thomas. “She didn’t kill herself. She was silenced.”

Sister Abhaya’s father — a low-wage farmer — fought tooth and nail for his daughter, Thomas said.

“We were poor people, we didn’t have much money,” said Thomas. “But my father would travel for hours a day by bus to probe the police to reopen the case and give us the truth.”

“He suffered a lot,” said Thomas. “He always said ‘someone killed my Beena. I am sure of it’.”

Activist pushed for answers

Days after news broke of Sister Abhaya’s death, the suspicious nature of the case piqued the interest of a young activist, Jomon Puthenpurackal.

“When I heard details about (Sister Abhaya’s) case — the overturned fruit basket, the ax in the kitchen, her slippers in different positions — I knew immediately that something bad had happened to her,” said Puthenpurackal, who said he was inspired by Kottayam-based freedom fighter, K E Mammen, to “do good in the world.”

“I knew she hadn’t committed suicide, like the police and the Church said,” he said.

Puthenpurackal soon formed an Action Council to get justice for the murdered nun. He took a signed petition, along with Sister Abhaya’s father, to the CBI, detailing all the allegations of corruption and listing key witnesses.

Every time the CBI filed a petition to close the case, Puthenpurackal kept the pressure on, using the Indian media to keep the case in the public eye, and urging investigators to dig deeper.

There was one witness, in particular, who had testimony Puthenpurackal felt was key to convicting the case. Adacka Raju was a “thief by profession,” according to court documents. He had trespassed onto the hostel campus on the night of the murder to steal copper plates from the terrace, which he planned to sell, according to court documents.

Raju had stolen copper plates from the hostel twice before. But on his third attempt — the night of the murder — he told the court that he saw two men approaching the staircase. He identified one of them as Father Kottoor.

During the trial, defense lawyers vehemently argued against Raju’s version of events and sought to discredit him, by branding him untrustworthy and a “man of no integrity.” They also alleged that he was a witness planted by the prosecution.

The prosecution, however, said Raju was taken into custody by the Crime Branch and kept in the station for 58 days. He was subjected to “inhumane torture” by officers there, who tried to extract a confession to pin the murder on him.

“He stood his ground and did not budge even an inch,” according to the prosecution. “He was offered a substantial monetary reward and a job for his wife and the meeting of the educational expenses of his children and a house to live in, but he did not succumb to these blandishments.”

The police even arrested an acquaintance of Raju’s, and tortured him for two days, according to court documents seen by CNN. The judge stated that the acquaintance’s brother was also arrested and tortured for six days.

He was repeatedly told to testify that Raju had committed Sister Abhaya’s murder.

“Raju faced many difficulties in coming forward,” said Puthenpurackal. “(The defense) completely dehumanized him. But he was one of the only witnesses who stood his ground, despite the mounting pressure.”

“I dedicated my life to this case and I wanted to see it through the end,” said Puthenpurackal, who continued to pursue the case even when it endangered his safety.

Father Kottoor who threatened Puthenpurackal at a protest for Sister Abhaya. According to court documents, Father Kottoor warned Puthenpurackal that he would be “handled in the proper manner,” also pointing out that “no one working against the church had ever been spared.”

Long wait for justice

Because religious authorities in India are held in such high regard, victims often find it difficult to come forward if their perpetrators are involved with the church, according to the former president of the All India Catholic Union, John Dayal.

However, in recent years a number of victims in Kerala have come forward to seek justice.

In April 2019, Catholic Bishop Franco Mulakkal was charged with raping a nun multiple times between 2014 and 2016. A group of nuns who spoke against his alleged abuse claimed the church attempted to transfer them to other parts of the country, in a bid to silence them. Mulakkal, who is now based in the northern state of Punjab, has denied all allegations.

Former Catholic priest, Robin Vadakkumchery was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2019 for raping a 16-year-old girl in Kerala. The incident came to light only after the victim gave birth in February 2017.

The victim and her parents attempted to redirect focus away from the priest. Her father went as far as telling the court that he was the one who raped his daughter.

Sister Abhaya’s parents died in 2015, before their daughters’ attackers were brought to justice.

“I just wish my parents could have been here to see it happen,” said Thomas, Sister Abhaya’s brother. “That’s all they ever wanted.”

Thomas said he “can rest in peace” and move on with his life, now that the case is finally over.

However, he said he still struggles to reconcile his sister’s love for the church with the horror of what happened that night — and the fact that those who purported to share her faith were the ones who “took her away.”

As reported by CNN