The Times of Israel attends the social-distanced burial of Anna Grosz, a ‘larger than life’ 94-year-old Holocaust survivor who was felled by COVID-19

CLARKSBURG, Maryland — Anna Grosz made the trek from her bedroom in a Northern Virginia assisted living facility to a window near the front lobby some weeks ago. Outside were her son and granddaughter.

With the help of the staff, she pulled up a chair by the window and got on the phone to speak with them. This was the safest way Grosz could spend time with her family as the novel coronavirus was spreading throughout the United States and claiming the lives of thousands. The outbreak has been especially pronounced at senior communities, where the rates of transmission have been high.

But Grosz has faced seemingly insurmountable adversity before: Born in 1926 in Racşa, Romania, she survived the Holocaust, including almost a year at the Stutthof concentration camp.

Still, according to her son, Andrew, she was acting out of character that day. “She started saying things like, ‘You remember when we did this? You remember when we did that? We had a good time. I’ve always loved you’ —which is something she never said very often to us,” the younger Grosz, 68, told The Times of Israel. “It was a given that she loved us, so I call that ‘death babble.’ She knew she was dying.”

Less than two weeks later, Grosz died of complications from coronavirus — just one day before her 94th birthday.

Yet as her loved ones would soon learn, her long and remarkable life would have to be memorialized in unusual fashion. Grosz’s friends and family held a funeral for her on April 22 at the Garden of Remembrance, a Jewish cemetery in Clarksburg, Maryland.

But, in accordance with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines, the cemetery only allows a maximum of 10 people to attend each service. It lowers the casket immediately, to keep the maintenance staff away from the mourners. And it makes sure every mourner wears a mask and gloves and stands at least six feet apart.

These regulations are part of social-distancing measures that state governments, including Maryland’s, have enacted to stop the spread of coronavirus, which has already killed more than 56,000 Americans.

The Grosz family didn’t opt for an online “Zoom service,” as others have, which allows virtual conferencing technology to connect people at a time when they have to be physically separated. Instead, the Groszes wanted a small and short ceremony, with no technology. They decided to hold off on a larger tribute, filled with eulogies, for another day.

“We decided that we’ll do that at the unveiling,” Andrew Grosz said.

During the funeral, mourners were spread out around a tent that covered the family plot. (Grosz’s late husband, Emory, is buried there.) The rabbi and Grosz children spoke briefly about her life, with an emphasis on her Holocaust survival and later efforts to increase Holocaust awareness.

“They told me it had a profoundly soothing and healing effect on them,” Kahn said. “All their dread of going through this alone was removed.”

According to Easton, families have been understanding of the restrictions imposed, even if they find them a bit unsettling.

“They’re all adapting rather remarkably,” he said. “I feel for their families, because Jewish bereavement is all about embracing the bereaved and being present — and people have to be present in very different ways right now.”

People have to be present in very different ways right now

At the same time, mourners keep finding meaningful ways to say goodbye under the circumstances.

“We had a funeral the other day where the son brought the shovel that he and his father used when they would plant a garden,” Easton said. “There’s all sorts of new symbolisms that one wouldn’t have expected.”

‘I couldn’t have imagined how she would have died’

Andrew Grosz said he was lucky to hug his mother one last time before she died. After she started showing COVID-19 symptoms last month, she spent a week at a Northern Virginia hospital. Given her age, she was considered at a high risk of dying from the infection.

Grosz, a geologist and geochemist who lives in Herndon, Virginia, was able to acquire personal protective equipment on his own, and the hospital staff allowed him and his daughter to see his mother while she was ill.

“We took a great chance by doing it, but we thought it was worth it,” he said, with a thick Eastern European accent. (Born in Romania, Grosz immigrated to America with his mother, father, and brother in 1964.)

He and his daughter, Diana, spent a half hour with matriarch Anna. By then, though, she was on a morphine drip and was already sedated. She died days later, all alone.

“I couldn’t have imagined how she would have died,” said Grosz, standing near her graveside, shortly after the funeral. “She was such a strong person, an amazingly strong person,” he added.

Anna Grosz’s experience living through the Nazi genocide scarred her immeasurably, he said.

“She came out of a camp — survive is perhaps the appropriate term — but she never fully came out of the camp,” Grosz said. “There were all kinds of emotional aspects to it for her. Her sisters passed on in one of the death marches out of camp.”

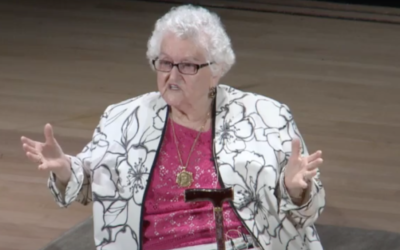

In her later years, Anna told her story widely and became a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

Her saga of survival will remain an essential part of her legacy, Grosz said.

And though he believes his mother deserved a bigger sendoff — “she was larger than life” — he suspects she would have appreciated the one she got, given the situation.

“Closure is not the word I would use after living 68 years with my mom,” Grosz said. “There is no closure — this is a forever deal. But I am glad we were able to do what we did. I think she would have liked that.”

As reported by The Times of Israel