Security officials say they’ve stepped up operations because of escalating violence emanating from the Palestinian neighborhood, home to 18,000

Since the start of the school year in September, Khader Obeid, the principal of the sole junior high school in East Jerusalem’s Issawiya neighborhood, has devoted a significant amount of his time to overseeing the commute of his students to and from classes.

Obeid, who has run the school for the past 16 years, said he spent more than four hours daily, standing outside its entrance to prevent the Israel Police from coming into contact with its 430 pupils.

In a series of interviews with The Times of Israel, Obeid, along with community leaders and members, argued that the police have unreasonably stepped up their activities in Issawiya and employed excessive force against its residents, undermining stability and stoking tensions in the neighborhood while complicating the students’ commute.

The police pushed back against the charges, asserting that heightened operations in Issawiya directly correlated with what they described as increased violence emanating from the neighborhood.

“I feel like I am no longer the principal of the school but rather its guard,” Obeid remarked. “Police have used force against many of our students, which has made it very hard for them to focus in class.”

Obeid said that some clashes had been triggered by students hurling rocks at police, but contended that police have often made false accusations against pupils.

Issawiya, one of several East Jerusalem neighborhoods, is sandwiched between the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Hadassah Hospital Mount Scopus, French Hill and Route 1, the primary highway that connects Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley.

More than 18,000 Palestinians live in the densely populated neighborhood. Amy Cohen, a spokeswoman for Ir Amim, an Israeli advocacy group, said it suffers from a major shortage of zoning plans and building permits, inadequate sanitation services, a lack of public spaces for recreation and insufficient classrooms, among other issues.

Even though Palestinians in East Jerusalem make up 38% of the city’s more than 900,000 residents, the Jerusalem Municipality only invests 10-12% of its budget in their neighborhoods, Daniel Seidemann, an expert on Jerusalem affairs, said.

Since Israel captured East Jerusalem in the 1967 Six Day War and subsequently claimed sovereignty, it has formally offered residents living in that area the option to apply for Israeli citizenship. Historically, very few have done so.

Recent years have seen a surge in the number of East Jerusalemites seeking Israeli citizenship, but many such applications have yet to be processed.

Months of friction

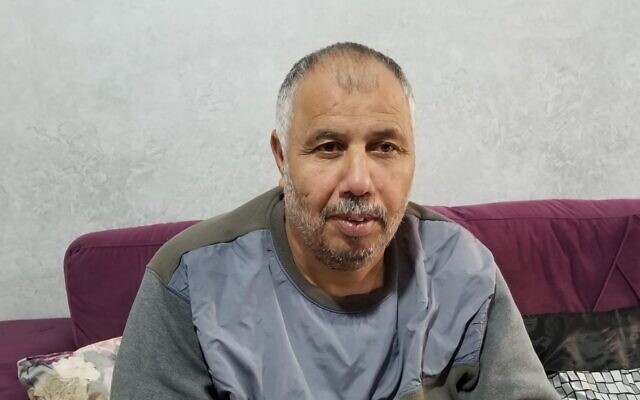

Mohammed Abu Hummus, a 53-year-old member of Issawiya’s Parents Committee, said the police’s heightened operations in the neighborhood go back to May 2019.

“At that time, they started causing lots of problems. So we held a protest on June 27 and then they came hours later and shot someone dead who did not pose a threat to them,” he said. “Since that day, they have been out of control and unnecessarily provoking and stirring up tensions.”

On June 27, the police shot dead Mohammed Obeid, a 20-year-old resident of Issawiya who security officials said had been firing fireworks at officers, endangering their lives.

Abu Hummus said that since May police have raided over 500 homes in Issawiya and arrested more than 600 residents — only about 20 of whom were indicted. He also said police officers have frequently set up roadblocks in the neighborhood, stopping drivers for questioning.

“This discrepancy between arrests and charges shows that the police has stepped way beyond its bounds,” he said, adding that he believed it has increased its activities in Issawiya to “force its occupation on us.”

“They know that we reject the occupation here. So they are now trying to make us gradually accept it as the status quo, but that will never happen,” he said.

Police spokesman Micky Rosenfeld rejected much of the criticism, arguing that the force had only taken action in response to violent acts perpetrated by Issawiya’s residents.

“We have recently dealt with many severe incidents in Issawiya including local residents throwing petrol bombs at Route 1 and attacking police with fireworks, Molotov cocktails and stones,” he said, stating that two police cars regularly patrol the neighborhood, with Border Police and the elite Yasam reconnaissance unit providing back-up during clashes.

“Our activities are a direct response to the major increase in violence that we have seen there,” he said, adding that residents recently targeted an ambulance.

Asked about Rosenfeld’s statements, Abu Hummus accused authorities of provoking residents into confronting them.

“When you come in here and wreak havoc, obviously there will be a response,” he said.

Violent clashes

Videos shared on social media over the past several months have shown residents and police officers taking part in violent clashes, with the former setting off fireworks and lobbing rocks, firebombs and other objects at law enforcement officers.

But other videos have shown police using significant force against locals. For example, in footage from November 9, a police officer hit 38-year-old Ahmad al-Masri in the face while arresting him, before throwing him to the ground. Later in that video, two officers pick up Masri and one of them punches him in the face. They then pushed him to the ground again and the second officer proceeded to hit him.

Speaking at a pizza parlor, Masri said the police officers had also used pepper spray against him and added that he had lost consciousness during the incident. He said he had originally approached the officers on November 9 to ask them not to park their van on what he described as his private property.

“What they did to me was barbaric and inhumane,” he said, adding that the police confined him to five days under house arrest several hours after spending a day receiving treatment at Hadassah Hospital Ein Kerem.

Asked about the video, Rosenfeld forwarded a statement that said police faced “a major disturbance that included an attack and lobbing of firebombs and rocks” on November 9, noting that two suspects were arrested and one officer was hospitalized after he was hit in the head by a rock.

The statement, however, did not name Masri as a suspect or make any explicit reference to him or the police’s use of force against him.

Seidemann said he was “completely baffled” by recent police operations in Issawiya.

“I have never seen anything of this scope, duration and intensity in Jerusalem since 1967,” he stated.

Failed efforts to reduce tensions

Meanwhile, principal Obeid said that the police, Jerusalem Mayor Moshe Lion and local leaders had agreed in late August to a formula whereby students could commute to and from school without seeing police officers.

“There was an agreement that the police will not enter the area during the hours students come and go from school,” he said. “The only problem was that police stopped abiding by the arrangement a couple of days after we agreed to it.”

Ben Avrahami, an adviser to Lion for East Jerusalem affairs, confirmed that “mutual understandings” were reached to “minimize friction” between students and the police, but said they were undermined by a number of violent incidents.

“What happened is students were throwing stones at the police in places that are not near the schools,” he said. “So the police came into town to deal with those situations, where they faced additional hostility.”

Obeid added that approximately a month after the initial agreement, the police, municipality and local leaders agreed to a new arrangement, creating a WhatsApp group with representatives of all three parties.

“The idea was that if there is any problem, it could immediately be solved through the WhatsApp group, but the police left it a few days after it was opened,” he said.

Rosenfeld said he was not aware of the WhatsApp group.

Avrahami declined to state whether he thought law enforcement was using excessive force in Issawiya, but emphasized that the municipality was undertaking measures to improve the situation there.

“Lion has been taking an active role in trying to be a bridge between the different parties,” he said, stating that the mayor personally initiated the meeting between police and local leaders in late August.

Avrahami also said that Lion recently ordered the construction of a playground in the neighborhood, which was completed in two weeks, and has taken action to advance a plan to construct a new community center there, too.

Mohammed, a 13-year-old resident, said he would like to see the situation improve.

“It is scary to be here,” Mohammed, who declined to give his last name, said. “I hope things will get better.”

As reported by The Times of Israel