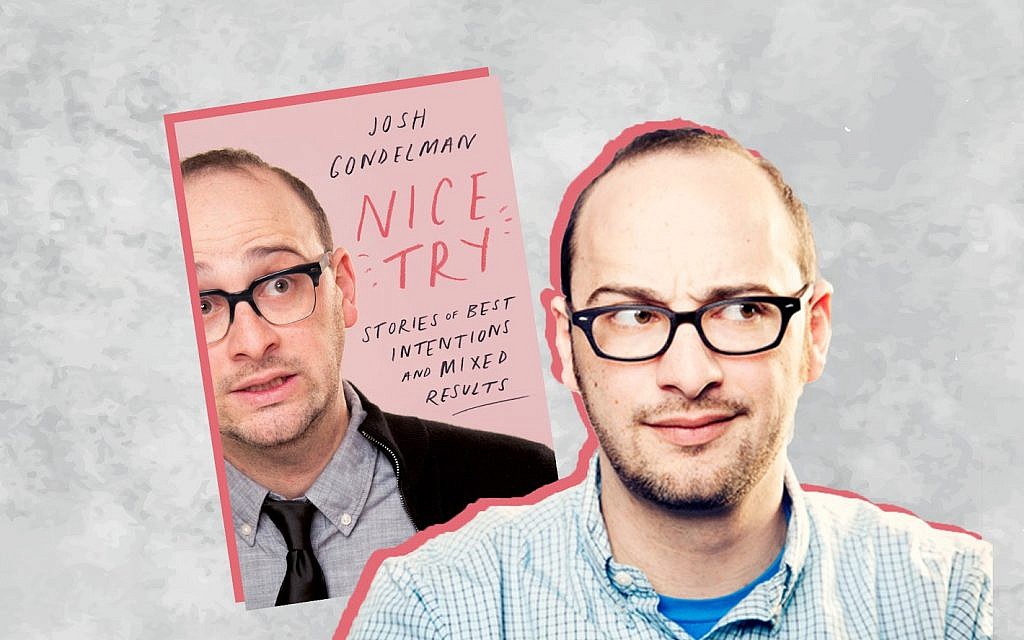

The comedian’s book, ‘Nice Try: Stories of Best Intentions and Mixed Results,’ out this past Tuesday, draws on Judaism to illustrate the contrast between ‘niceness’ and ‘goodness’

JTA — Comedian Josh Gondelman wants you to know up front: He’s a nice Jewish guy.

“I’m Jewish. I was bar mitzvahed, and I enjoy the ritualized eating of carbohydrates. But more than that, I was raised nice,” he writes in the opening meditation on “nice guys” in his new book, “Nice Try: Stories of Best Intentions and Mixed Results,” which came out September 17.

In that way, Gondelman, 34 — who won three Emmys for his work on “Last Week Tonight with John Oliver,” and currently works as a writer and producer for the Showtime series “Desus & Mero” — is a bit of an outlier in the modern world of comedy, which often values mocking and R-rated themes.

Why open with talking about being a nice guy?

“It sets the tone for the overall arc that’s going to happen,” Gondelman told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “There is a strong element of Judaism, which is obviously important to me, but the book really focuses on niceness versus goodness.”

It’s a deeply enjoyable arc: The essays cover everything from Jewish summer camp to working as a preschool teacher to romantic failures, and they are laugh-out-loud funny. Which makes sense — in addition to working on those shows, he has also had a successful stand-up career and back in 2012 started the popular Modern Seinfeld Twitter account, which won hundreds of thousands of fans by imagining what contemporary episodes of “Seinfeld” would involve.

Gondelman spoke with JTA about the concept of “niceness,” his favorite Jewish holidays, discovering the Wu-Tang Clan at Jewish sleepaway camp and his evolving thoughts on Twitter.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JTA: How do you distinguish between niceness and goodness?

Gondelman: Niceness is pleasantness and politeness and the kind of surface-level things you do to get by, which are important. And then goodness is kindness and righteousness, and sometimes it’s the same as niceness, and sometimes it’s in conflict.

I really resonated with your chapter about trying to apologize less.

Oh, yeah.

It is something that I find so challenging. You write about how your favorite part of Judaism is that time between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and how you used to write a mass apology email. What was in those emails? And why did you stop sending them?

It was a recurring thing that I did. I would try to be very sincere [and] email a lot of people in my life. It was a vast mass email. I would give a little primer on Yom Kippur, and then say, so in that spirit, if I have done anything that was hurtful to you that I didn’t realize, I want to say that I’m sorry and I would love to restore whatever was breached.

It’s different than [writing], “I’m sorry if you were offended” because there’s a value to being like, “Hey, if I did something that I didn’t realize, like please let me know. This is the time where I would like to clean the slate.”

It’s nice to have a moment [where] it’s easy to explain why am I hitting the reset button today. It’s a nice excuse, as opposed to just doing it on like a random Sunday afternoon. I don’t know, people might go “Why is this? What is this?”

Yeah, it gives it context.

It does. It gives it a context, which is a really beautiful thing about Judaism. There’s moments that are like structures for being a good person. [It’s] the kind of thing that I appreciate most about any kind of religion: These opportunities to go and do better and be reminded of the best ways to behave and treat people.

One of my favorite parts of “Nice Try” was when you wrote about your time at sleepaway camp. You talk about discovering rap music. I love how you connect studying for bar mitzvahs and learning rap music with “learning and parsing dense, opaque lyrics,” but “only one felt like it prepared you for adulthood.” How formative were those years for you?

Some of my best friends are the guys that I went to camp with those years. We’re still in super close touch. I have a couple of close friends from high school and college, but numerically a disproportionate amount of the people that I still consider really close to my heart were the guys [from camp].

That brings me to my next question: You write a lot about the impact of the Beastie Boys on you. Why do you think the Beastie Boys were so important to you and to young Jews more generally?

I think the Beastie Boys are like the cool Jewish kids that you know. They were visibly and clearly — by their proclamation and by their heritage — Jewish, but were also doing cool stuff. Their music was both really enmeshed in the broader hip-hop culture, but also didn’t feel like they were putting on airs or pretending to be people they weren’t. They were goofing around and having a good time. It was like, oh there’s a place to be a sarcastic Jewish kid. [Their Jewishness felt] more modern than the Mel Brooks and, at the time, the Woody Allen version of popular culture male Judaism.

They’re very important to me. They felt like such an entry point into this world that I felt like I didn’t have access to; there was a point of commonality being white guys, but being Jewish guys specifically. When I heard Eminem, I wasn’t like, oh that guy is me! When I heard the Beastie Boys, I was like, oh, there’s a way to appreciate and have access to this world in a way that’s not appropriate or disrespectful and that feels related to my own life experience.

What’s your favorite Beastie Boys album?

Oh, man, I think it’s become “Paul’s Boutique.” It’s just so out there and so silly. I think [they] made it in L.A., but there are parts of it that [are] nitty-gritty New York stuff, so it feels like this weird hybrid of West Coast sonics and East Coast reference points.

Switching gears a little: You’re very visible on Twitter, and the social media platform has been a large part of your career. What’s your relationship to Twitter these days?

I’ve had so much good fortune with it, professionally and personally. It’s like if you fell into a sewer and found $100, and you fell in a second time and found a diamond ring, and you’re like, wow, this sewer has been really good to me. Even though it is full of human waste.

Can you talk about the origins of your Modern Seinfeld account?

I started one afternoon — I think while I was seeing a tutoring client, while they were doing a practice test — I started tweeting a couple things of like, here are some Seinfeld plot lines that might happen if the show was on now. I was doing it kind of idly and my friend Jack saw it, and [said] “This should be its own thing.” He immediately jumped on the Twitter handle [@SeinfeldToday]. People really latched onto it, which was very incredible.

A lot of credit to Jack Moore’s vision. It was a lark that turned into something that people really got into. Part of it is that we did a nice job executing it, but the other part is that people just have so much affection for “Seinfeld” — and “Curb.” [It’s] a specific, beloved thing for a generation of people, if not more than one generation. It was very nice to stand on the shoulders of giants in that respect.

One thing you still do on Twitter is give pep talks to strangers. You write about this in “Nice Try,” but could you talk about why you decided to start?

I started doing it [when] I felt kind of down about certain things. I [thought], I could ask for something online and say, “Hey, does anyone have any ways to feel better?” Or, you know, “Is there anyone that wants to book me for a show?” But [I thought], I bet I’ll get the same charge out of trying to do something for someone else. So, I said, “if anyone needs to hear a kind word, I’ll be here for five minutes.” This is maybe six, seven years ago. So I did that, and it went well, and it was fun. And I got the thing out of it that I wanted.

Hi! If anyone needs a pep talk I’m here for five minutes! Just let me know!

— Josh Gondelman (@joshgondelman) Hulyo 13, 2019

I hope that, first and foremost, they have a fun time reading it. That it feels warm and funny. I want people to enjoy it thoroughly, and to come away being like, wow, what a good time, I feel better than when I started because it was invigorating and entertaining.

The second thing is, if there’s a good other level to it, I want people to take away that things are often hard and bad, [but] they can get better. There are things to latch onto amongst how difficult things are. One thing that is really inspiring to me is people doing really hard activist work, and people really standing up for what they believe in. So I hope that there’s like a little bit of encouragement.

As reported by The Times of Israel