In his new book, Prof. Stanley Goldman unearths a personal untold story, learning about his own relationship with his mom, as well as the siblings he never knew

Malka didn’t cry as she was about to enter the gas chamber.

She and the other women in her group had arrived in Auschwitz from the Lodz Ghetto the week before. Now they stood bald and naked. A plume of smoke curled upwards.

Suddenly, the female SS guard ordered the 500 women to fall in line. Guards led them away, gave them clothes and then crammed them onto a train bound for a German munitions factory outside of Berlin. Thus was Malka “spared by a randomly serendipitous consequence of evil,” wrote Stanley Goldman in his new book, “Left to the Mercy of a Rude Stream: The Bargain That Broke Adolf Hitler and Saved My Mother.”

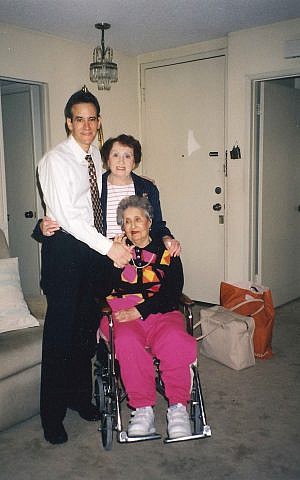

Part history and part memoir, Goldman’s book mines the terror of his mother’s captivity, her unlikely survival and the long-term effects of her experience on both of their lives. Because Malka never shared many details about the war with her son it wasn’t until 2012, years after she died, that he summoned the courage to tell her story.

“I set out to tell my mother’s story, her time in the camps, her rescue. I had not planned to write about my mother and me. But a friend of mine once said I am the epitome of children of survivors. Although there was a visceral pain of having to relive certain moments of my life, I realized I had to include my relationship with my mother,” said Goldman, director of Loyola University’s Center for the Study of Law and Genocide.

Because his mother spoke so little about her experience, save for one bedside interview, Goldman had several interviews with his mother’s friend Genya Morag (who survived the camps with her) and Genya’s daughter Dvora Morag. He researched the archives at Yad Vashem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Additionally, he relied on previous research and articles he’d written for the Loyola Law School International and Comparative Law Review.

While delving into his mother’s story he discovered how chance often conspired for and against her.

To start, Malka was almost born in the United States.

Goldman’s grandfather and grandmother had arrived in the United States just after World War I. But they grew homesick and returned to their Polish shtetl, Biala Rawska, where the couple had nine more children, including Malka.

Eventually, Malka married. She had a son named Archie and a daughter named Genya. When the Nazis rose to power Malka and her family were forced into the Lodz Ghetto. The Nazis shot her husband several months later, and in 1942 loaded the children of the ghetto onto trucks. They drove them to a camp along the Ner River at Chelmno, where they were gassed.

After the ghetto was liquidated Malka was sent to Auschwitz, then the factory near Berlin, and ultimately to Ravensbrück. She would have perished there had it not been for one man’s negotiation with Heinrich Himmler.

Norbert Masur, a German-born representative of the Swedish branch of the World Jewish Congress, flew to Berlin and met with Himmler. According to Goldman, Himmler realized the end of the war was near and hoped the Allies would go easier on him if he released some Jewish women from Ravensbrück. Goldman’s mother was among those freed.

Serendipity spared Malka once more.

Over the years, as Malka rebuilt her life in California, remarried and raised Goldman, she only occasionally mentioned the camps. While Goldman was growing up he simply sensed that it was a taboo topic. When Goldman finally pieced her story together and faced the legacy of her trauma it changed him — literally.

“I’m turning 70 soon and people have always believed I dyed my hair. My friends, their wives — they ask me what I use,” Goldman told The Times of Israel in an interview from his home in Los Angeles. “I don’t dye it. I’m not joking. But then I started writing about my mother and me. In six months my temples turned gray.”

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Can you speak a little about your decision to write this as part memoir, part history?

When I was a young man looking at the Holocaust Museum here in Los Angeles, I came across something about the 500 women [saved from Auschwitz]. I looked into it a little more and decided I wanted to write about my mother’s rescue. After working on the book for a few years I knew I had to write about my mother and me, but there was a lot I had never told anyone.

I had never told anyone about how my father died of a heart attack. I had never talked about how my mother said her son [Archie] had “dressed himself perfectly” on the day the Nazis took him. I had never told anyone about putting my brother and sister’s name next to my mother’s name on her gravestone. The book was a way to talk about it.

How did you process learning about your brother and sister?

I did not think of them as my brother and sister until I was in my 30s. I always thought of them as my mother’s first two children. I had tried to keep a distance from them because it was too painful. I also didn’t want to find myself sympathizing with [my mother]. She was my combatant then, she was forever trying to control me.

Not thinking about them like that was a way to protect myself. It wasn’t until I started confronting my relationship with my mother that I began thinking of them as my siblings. It was a revelation.

Did you ask your mother questions about her experience when you were growing up? Or was it more of an unspoken understanding that you wouldn’t ask and she wouldn’t tell?

Once, when I was in my teens, I asked her if she ever tried to find out if my brother and sister really had died. Did she see them killed? Did she see them dead? She didn’t answer.

Although I lived alone with my mother from the time I was about 11 until I was 40, my mother really never talked about her experience. Sometimes she let little things slip.

Then, after she had her first stroke I sat at her bedside and recorded a half hour interview with her. One of the very first things she spoke about was her son and daughter, my brother and sister, being taken away.

How does your book fit into the rise in Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism?

Maybe it’s the way I was raised, but anti-Semitism ebbs and flows. These things get quiet but never disappear.

I was speaking to the LA County Bar Association the other night. The main question people asked was “Why would Himmler want to talk to a Jew about anything?” It’s like today when people talk about George Soros, or the killer in New Zealand whose manifesto reportedly mentions the Jews. It’s the anti-Semitic idea that Jews have power and are controlling and manipulative. That is the book’s biggest parallel to today.

We talk about “Never Again,” yet, since the Holocaust there have been Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and other genocides. What then is the lesson, or message, in your book?

My conclusion, after researching this book, is that Homo sapiens are wired to have very negative feelings about the other: to fear them, to hate them, and to want to destroy them. That’s not going to change in 100 years or 1,000 years. I don’t care who you are; all of us have some of this buried inside us.

If nothing else then, this book shows us we must be vigilant. We must be vigilant in Hungary and we must be vigilant in Poland. We must be vigilant in Austria and we must be vigilant in the United States.

As reported by The Times Israel