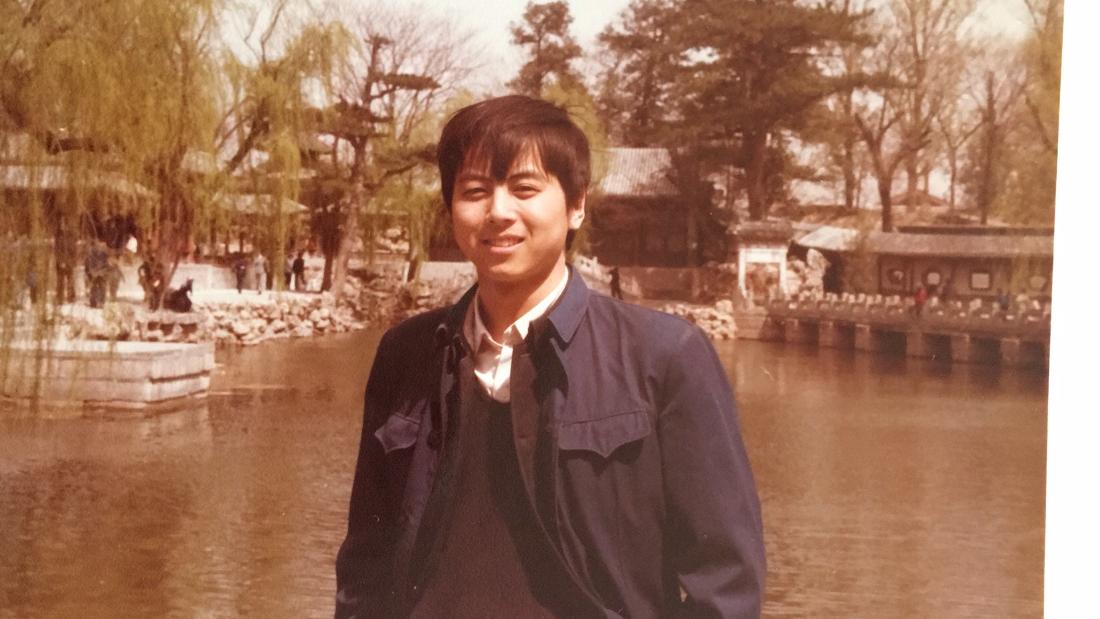

Beijing – Thirty years ago, in the heart of the Chinese capital Beijing, Dong Shengkun threw two flaming, gas-soaked rags at a military truck after a night of bloody violence in the city. It was a move that would ruin his life.

Then a 29-year-old factory worker, Dong was given a suspended death sentence on arson charges and spent 17 years in prison. It changed his family forever — his father died and his wife divorced him while he was in jail. Dong’s son was just three years old when his father went away.

But despite the impact it had on their lives, Dong has never discussed what happened in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, with his son, now aged 33.

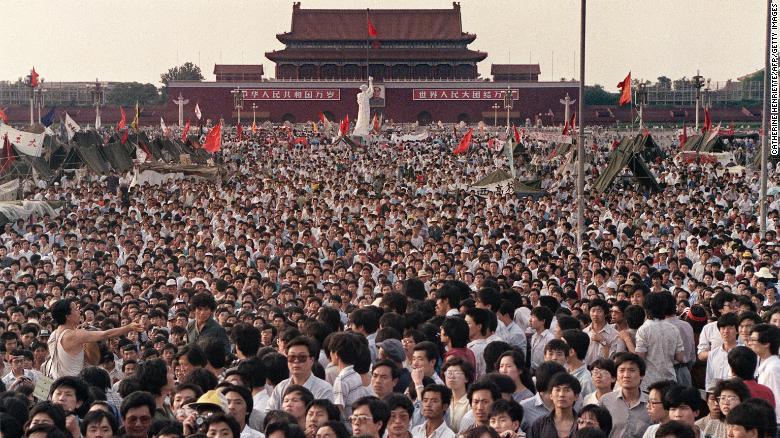

The brutal massacre of hundreds, if not thousands, of protesting citizens, workers and students in Beijing shocked the world. For China, it marked a turning point away from the prospect of greater freedom and towards authoritarian oppression.

But Dong would prefer to have his son think he is just a regular criminal, at least in the current political climate in China, than be potentially put in danger by learning of his father’s political past.

“It is for his safety,” Dong said. “I worry that I might influence his thoughts if I started chatting to him about those things.”

Other former political prisoners have expressed concerns about talking to their children about the massacre, for fear of putting them at risk.

Fellow Tiananmen survivor Fang Zheng, 53, said he doesn’t blame Dong, and other former activists, who want to shield their children from politics. Fang, who lost both his legs in the massacre, blames the ruling Communist Party.

“That’s the fear and horror that the regime has brought to everybody,” he said.

Massacre erased

Dong said he believes his son is not alone in his relative ignorance of the dramatic events of June 4, 1989.

Three decades after the Chinese government declared martial law and unleashed the military on unarmed students and worker protesters, the bloodshed has been largely erased from the nation’s collective memory.

The Communist Party-led effort has created a generation who are mostly unaware of the Tiananmen massacre, Dong said. School textbooks don’t mention it and students won’t find photos or stories of June 4 on China’s heavily-censored internet.

The crackdown followed weeks of protests in Tiananmen Square, a massive plaza fronting the Forbidden City and the Great Hall of the People. Demonstrators called for greater political openness, including freedom of speech and democracy, to match the country’s growing economic liberalization.

After fierce debate at the top levels of the Chinese government, the hardliners won and called in the military. The death toll from the protests in Beijing may have been in the thousands, according to some estimates.

“I saw a few students were trying to climb over the fence and evacuate from the square, and a tank went straight there and crushed them to death,” Dong said.

No public memorial or commemoration ceremonies will be held in mainland China to mark the 30-year anniversary on Tuesday. On the country’s internet, monitors will work overtime to delete any mention of the massacre — part of a decades-long government effort to erase memories of Tiananmen.

Several popular video streaming websites have been ordered to close their live commentary functions in the lead up to the anniversary.

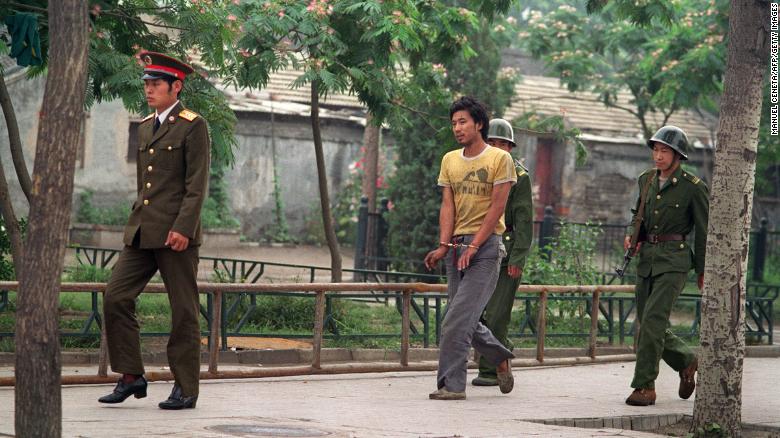

Anyone who dared in the past to publicly commemorate or even mention the events of summer 1989 was silenced.

People who tried to light candles where protesters died along Changan Avenue or near Tiananmen Square were arrested.

Former protesters who had experienced June 4 and tried to speak to media about it were stopped, warned and monitored by the police.

Soon, people stopped talking and started forgetting. According to Dong, they did it for their own good.

“In those days, many people received severe punishment for little things,” Dong said.

At the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore on Sunday, Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe described the Tiananmen protests as “political turmoil that the central government needed to quell.”

“The government was decisive in stopping the turbulence, that was the correct policy,” he said.

‘They’ve got no choice’

Ahead of the anniversary, Dong and his friends, Zhang Maosheng and Zhang Yansheng, met at a restaurant in Beijing for a rare reunion to commemorate those who died that day and to seek comfort from each other for their own losses.

The three joined the rallies separately when they were in their 20s, and still young and idealistic.

In the final days, both Dong and Zhang Maosheng tried to set fire to military vehicles while Zhang Yansheng destroyed a police videotape that showed civilians blocking military vehicles from moving into the square.

Dong said he joined the thousands of students in the square because he wanted an end to corruption, even though he didn’t understand what “democracy” meant.

But he and his friends have paid a heavy price — along with Dong, Maosheng was given a suspended death sentence while Yansheng was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Like Dong, Maoshen and Yansheng were released after serving 17 and 14 years in prison, respectfully.

Talking over a beer, they agreed that the sacrifices they made, along with those who died on June 4, were too dangerous to remember in modern-day China — adding many young Chinese have never even heard of the Tiananmen Square massacre.

“Those who are the same age as us or older saw it happen, but they are too afraid to talk,” Zhang Yansheng said. “And those who are younger than us never even knew it happened.”

Their own children will be among those to remain in ignorance, at least for now. Zhang Maoshang said he won’t tell his two young daughters things “that can only bring them trouble.”

“The society we live in is not open or safe enough, and I want them to be able to grow up without fear or worries,” he said.

Survivor Fang Zheng said the Communist Party believes its very legitimacy depends on covering up the events of June 4 — and so far it has been hugely successful at doing so.

“At present, under the rule of the current Communist Party government, most of the people would hedge, stay silent, or even necessarily cooperate when they come to their children, or to themselves. They’ve got no choice,” he said.

Good and brave

The three men’s fears for their children appear to be borne out by recent events.

Ahead of the 30th anniversary, student activists have been disappearing again in Beijing, after members of the prestigious Peking University Marxist Society announced plans to show support for workers’ rights.

More than a dozen of their members have disappeared or been detained since August 2018. Six vanished ahead of International Labor Day on May 1.

As for the three ex-prisoners at their restaurant reunion, their focus — like that of most Chinese — is now on their families and on seeking a better life, rather than dangerous questions of politics.

“Even my wife tells me, ‘Stop thinking too much about all this, so unrealistic.’ She says, ‘Why don’t you hurry up, find a proper job and earn a bit more money?’ What’s more important than looking after your wife and kids?” Zhang Maosheng said, downing his beer.

But speaking in a text message later, Zhang Maosheng said he hoped one day, in a different China, to tell his children about what their father did in 1989.

“After they’ve become adults, and after China becomes a better place, which I believe it will, I would love to tell them what their dad had done,” he said. “Because what I did was good and brave.”

As reported by CNN