The American-raised son of an Israeli, author Oren Jay Sofer found spirituality later in life and has now written the book on how our universal human needs can help us connect

Raised a Reform Jew in the Northern New Jersey suburbs, meditation and communication teacher Oren Jay Sofer found his way to spiritual practice only as a young adult in his 20s. His route to enlightenment followed a series of failed romantic relationships, lost friendships, and his parents’ divorce.

Sofer didn’t connect spiritually to Judaism as a child and young adult. And while he and his mother would have deep, spiritually minded conversations in his youth, it wasn’t until much later, after studying comparative religion at Columbia University, that he would discover and explore the mystical aspects of Judaism.

Raised a Reform Jew in the Northern New Jersey suburbs, meditation and communication teacher Oren Jay Sofer found his way to spiritual practice only as a young adult in his 20s. His route to enlightenment followed a series of failed romantic relationships, lost friendships, and his parents’ divorce.

Sofer didn’t connect spiritually to Judaism as a child and young adult. And while he and his mother would have deep, spiritually minded conversations in his youth, it wasn’t until much later, after studying comparative religion at Columbia University, that he would discover and explore the mystical aspects of Judaism.

“In a different time, I might have been a rabbi,” said Sofer, now 41 and a practicing Buddhist. He’s also a certified trainer of nonviolent communication, as well as a somatic experiencing practitioner for healing trauma. “But that’s not the form my spirituality takes. I consider myself culturally and ethnically Jewish, but I’m not a practicing Jew in terms of religion.”

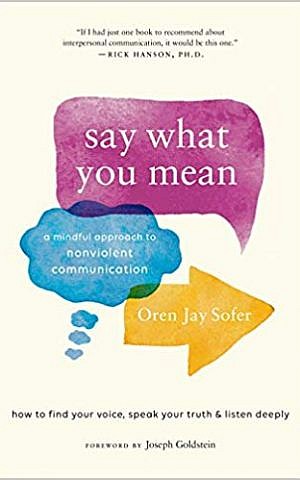

As he shares in his new book, “Say What You Mean: A Mindful Approach to Nonviolent Communication,” Sofer originally turned to meditation as a way of sorting out some of his “inner turmoil.”

“It’s quite fascinating what drives people to spirituality and contemplative practice,” Sofer reflected in a recent interview with The Times of Israel over Skype, “and suffering is definitely one of the most common ways.”

He’s quick to add that “suffering is a strong word” that describes an emotional response to a wide range of experiences; anything from basic stress and trouble sleeping to relationship difficulties and grief over loss.

“Say What You Mean,” Sofer’s first book, is the result of his many years studying, using, and teaching nonviolent communication (NVC) — a method devised in the 1960s by Marshall B. Rosenberg for expressing and receiving communication empathically. At the heart of NVC is the premise that all humans share the same basic needs, have the capacity for compassion, and that habits of thinking and speaking which lead to violence are culturally developed (and can be unlearned).

After being approached by his publisher with the idea of compiling his mindfulness and NVC teaching experience into a book, Sofer said he sat down and wrote the first draft over a period of a few months.

“This material has been in me for some time,” he admitted. The final product is a 250-page book that deftly weaves together engaging personal narrative with communication exercises to be done alone or with a partner, as well as useful strategies for a variety of typically challenging interpersonal exchanges.

Further, Sofer assembled questions asked over the years by his students, the answers to which he believed would be beneficial to the reader. Ranging from how to reduce anxiety before and during difficult conversations, to how to stay focused on what really matters in an interaction, the Q&As are a welcome interlude at the end of each chapter.

“As I say in the introduction, my aim is not to share theories, but to give people something practical in their life. The theories are fascinating and beautiful, but it’s not a book about meditation or trauma healing. It’s a book about communication and relationships. And so the focus for me was how to give people a step-by-step guide to transforming their communication and relationships,” Sofer said.

While the book is not focused on healing trauma, Sofer, the son of an Israeli, who spent time both as a child and as an adult visiting his father’s family in Herzliya, believes that nonviolent communication and mindfulness practices can certainly contribute to healing of both personal and collective trauma, whether in Israel or elsewhere.

“I’m glad you didn’t ask me how we were going to solve the crisis in the Middle East,” Sofer said with a smile, in response to be being asked about how to maintain hope for mindful communication and healing in a region that is in the ongoing midst of deep division, turmoil, or war.

“There are two different levels of the answer to such a question, and both are true,” said Sofer.

“One, we need to develop resilience and rely on the support of community. Anything worthwhile in life takes effort. Working for peace or transformation is a quintessential example of that, and so we must develop inner resources to learn how to nourish oneself, to have a very clear and solid practice of self care, and to not do it alone, but to do it with others,” Sofer explained.

Unfortunately, this is often quite difficult even for well-intentioned individuals, as so much of our society is disconnected and individually focused.

Sofer explains the biological source of this tension in his book: “So much about our society doesn’t support the kind of familiar relaxation that our organisms long for: the ease of warm connections and sense of place.”

The other dimension involved in maintaining the inner strength necessary to work toward transformation is letting go of the outcome, said Sofer.

“We may believe in the possibility of human beings living together in a different way. And yet, in order to sustain the work, we need to recognize the outcome is out of our hands,” he said.

It’s when we become too focused on the results of our efforts — whether it’s peace in the region, sustainability, or political collaboration — that we begin to feel hopeless or resigned, Sofer said.

While “Say What You Mean” is intended for use at the individual level, the appeals Sofer makes in the book for individuals to lean in toward compassion, curiosity, and caring can certainly be applied on the communal level, whether those communities are the neighborhoods we live in or the larger groups we feel a part of, such as the workplace, educational institutions, or even online.

“Some of the most healing and nourishing experiences I’ve had have been living in community. For me, this happened at Elat Chayyim, a Jewish renewal center in New England, as well as living in a Buddhist monastery. Basically, any place that fosters close knit relationships, and where we all are working together toward a common end, can support healing,” said Sofer.

“We all communicate all day long,” he said. “It’s the primary thing determining the quality of our relationships. You don’t need to become a communication master to experience changes. One small shift in your communication can have far reaching impact. And with that comes encouragement and hope.”

As reported by The Times of Israel