Even as demand for literature is on the rise, online bookstores make it nearly impossible to sustain a fixed literary space for secular ‘Jewish’ works by fledgling writers

LONDON — It is the best of times and the worst of times for the local British Jewish book scene.

Novelists such as Howard Jacobson, who penned the polemical novel “The Finkler Question,” and more recently Francesca Segal and Naomi Alderman — whose book “Disobedience” is currently out as a film — are achieving global fame.

An attendant rise in prestigious literary events includes Jewish Book Week, with wall-to-wall discussions involving renowned authors and national opinion-formers, as well as celebrity book launches at the cross-communal center JW3 which can attract up to 300 people.

However, 2018 also marked a new low in the printing of Jewish titles in the UK.

According to Martin Kaye, whose book distribution company, Kuperard, supplies faith titles across Europe, the quantity of new Jewish titles he supplied to the UK market has “dropped to just 10 in the past year from 50-60 a decade ago.”

“For example it was disappointing not to see any mainstream or Israeli house publishing a large format volume to celebrate Israel’s 70 years,” Kaye added.

The success of the mega names, who are available in large book stores like Waterstones, can’t mask the lack of publishing of wider Jewish titles. This is partly because “religious” book shops, which largely sell books on Torah and religious philosophy, don’t often stock them.

“Whereas 20 years ago one or two religious shops stocked a reasonable amount of wider Jewish literature, that is no longer the case. And this will lead to ignorance about the wider Jewish experience,” said Kaye.

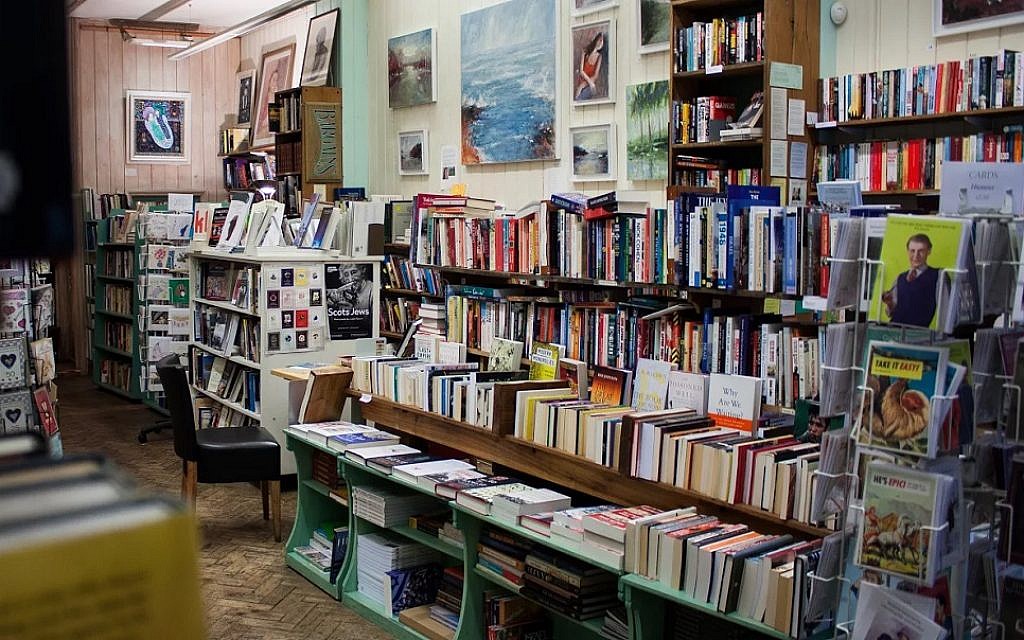

The closure of the community’s only cultural Jewish bookstore, Joseph’s, earlier this year, has brought the matter sharply into focus. Conceived of in 1993, Joseph’s combined Jewish and general interest books. The literary salon included a restaurant, recitals, publishing and art.

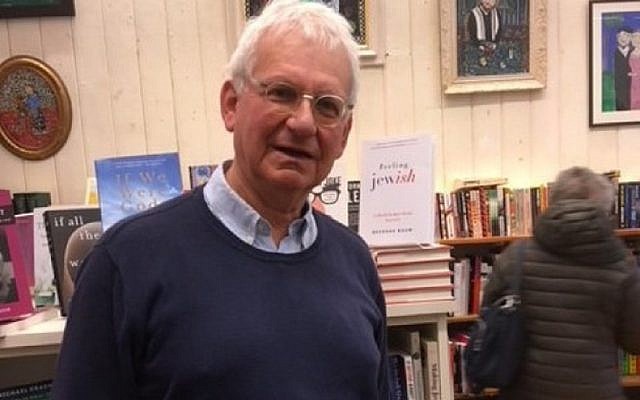

“It’s a shame that wider Jewish literature can’t find a place in religious bookstores,” said the store’s founder, Michael Joseph, who closed down the store upon his retirement at age 74. “Part of the reason I created Joseph’s was because I wanted a neutral space where people could engage in Jewish culture rather than merely religiosity.”

Joseph, like Kaye, believes there is the demand for Jewish literature, but that it is not being met.

“I have no doubt general stores having regular sections of Jewish interest would work, as ‘Jewish authors’ sell. Unfortunately, the big chains are increasingly centrally managed, and don’t always have the feel of the local reader,” Joseph said.

Kaye, who cites “the buoyancy of the Catholic community’s publishing,” believes that “the local Jewish community needs to do more to support the visibility of the Jewish novel and Jewish history books.”

He notes that translated Yiddish classics by the likes of I.L. Peretz and Sholem Aleichem are no longer kept in print by major houses.

“There is a huge appetite for cultural Jewish literature in our community across the religious spectrum, and frankly, if it’s not stocked under one roof somewhere, it won’t be properly satisfied. We will be left with a few bestsellers, but not much beyond that,” Joseph claimed.

Between 1997 and 2003 Kaye ran a successful pop-up bookstore for Jewish Book Week. Stocking 10,000 books from publishers from around the world each year, he sold three-quarters of them.

“Our purchasers ranged from universities to public libraries, both UK and European, with many individuals surreptitiously stocking their home libraries,” he said.

Despite adapting to a world of online sales — “99 percent of our sales of Jewish interest books are through online retailers” — Kaye stresses that shopping through Amazon is not comparable to being in a bookstore.

“Customers essentially just type in a specific title, rather than browsing an array of options,” he said. “This trend will mean people will stop looking at the range of new works on Jewish history from Israeli scholars,” he predicted.

“People will become ignorant of the Anglo-Jewish experience — for example communal scribes like Cecil Roth and Israel Zangwill — as well as missing out on entirely worthy contemporary novelists,” he said.

As London’s first multi-denominational Jewish community center, JW3 could be a natural location for such a new bookstore. It certainly has the built-in foot traffic: the center welcomes 4,500 visitors every week.

Its chief executive, Raymond Simonson, says he buys Jewish novels in his local bookstore “which caters for that culturally Jewish market that one sees a lot nearby JW3.”

The center’s Hampstead location is very much still marked by the Jewish emigre intellectualism typified by father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud and political philosopher Isaiah Berlin.

Under Simonson, JW3 has hosted book launches for renowned popular historians Simon Schama and Simon Sebag-Montefiore, as well as Human Rights lawyer and author Phillipe Sands. Celebrity chefs Yotam Ottolenghi and Nigella Lawson have also been among the offerings.

A similar trend for top-level events has taken place at Jewish Book Week. That initiative’s prime time events in central London’s King’s Cross are supported by a daytime home at JW3, whose more suburban location adds to its numbers.

In addition, the local literary scene will converge on JW3 in February for the prestigious JQ Wingate Literary Prize — the only UK literary award to recognize authors and writing that explore the idea of Jewishness to the general reader.

“It is wonderful that in 2018 judges continue to be faced with a plethora of books to debate and consider and that there is still a considerable interest both in reading and writing books of Jewish interest,” Wingate Prize director Juliet Simmons told The Times of Israel.

Joseph endorses the sentiment that, “The Jewish novel, in all its forms, will continue to be popular within the Jewish community and outside.”

Despite this, Joseph closed down his beloved book store nine months ago. He acknowledged that the business of running a niche Jewish bookstore is a losing battle.

“Unfortunately, just like many small bookstores, we faced the challenge of competing with online bookings, for example Amazon. It was hard to see people coming in to browse our selection, knowing they were often going to be purchasing them online,” Joseph said.

He added that the trend of pop-up, moveable bookstores is also unlikely to pay the bills. “The business side is rather low-margin and requires high volumes of sales. It takes a lot of patience to schlep the books around for limited yields,” Joseph said.

Not that replicating Joseph’s would be easy: The bookstore was rather like a storefront Jewish community center.

As befits someone who runs a community arts center, JW3’s Simonson says he is “open to conversations about having some sort of a bookstore here.” But ever the pragmatist, he adds the initiative would require support from book publishers.

“The challenge is it would need to at least break even,” he says.

As reported by The Times of Israel