San Francisco – A Jewish inmate serving life in prison without parole took a step toward freedom Aug. 21 and credited the local Jewish newspaper for the turn of events.

James A. White Jr., was sentenced in 1981 for the murder of his wife’s ex-husband.

Last week, California’s Board of Parole Hearings unanimously voted to recommend commutation of his sentence after 37 years behind bars, in part because of the work he has done in establishing a community college program for fellow inmates.

That program was given wide publicity earlier this year in an article on White by Alix Wall in J. The Jewish News of Northern California.

“There’s no doubt in any of our minds that it was your article that was the impetus that forced them to deal with my case,” White told Wall last week in a phone call. “Your article changed my life.”

White, a decorated Vietnam veteran, is credited with establishing the community college program — allowing inmates to work toward an associate’s degree — at Ironwood State Prison in Riverside County. (He has since been moved to the California Medical Facility prison in Vacaville in Northern California’s Solano County.)

Some 1,500 Ironwood prisoners have graduated from the community college program since its start in 2001. A 2013 study by the Rand Corp. found that inmates who participated in educational programs were 43 percent less likely to return to prison within three years than those who did not participate.

The next scheduled stop for the case is the state Supreme Court; after that, it is expected to go to Gov. Jerry Brown, who has the power to commute White’s sentence. But the hearing was the main hurdle.

“He’s not out till he’s out,” said Rabbi Mendel Kessler, who knows White through his work as a prison chaplain. “But I’m 99 percent sure.”

One of the inmates White helped was Ryan Lo, who was released from prison in 2014 after serving 23 years on a murder he committed as a juvenile and now runs a project documenting the experiences of former inmates. Lo was one of the 13 people who attended the board hearing in Sacramento.

“This crazy, old, Jewish guy came by my door and introduced himself, and said, ‘I’m James White,’” Lo said. White insisted Lo take college courses, and didn’t let up. Lo completed six associate degrees in prison and says White changed his life. In return, he made a promise.

“If I ever do go home, I promise you I will do everything in my power to bring you [White] home with me,” Lo said he told himself.

Kessler, who was a chaplain at Ironwood and is now the director of Chabad of Sedona, Arizona, also spoke in favor of White. Calling himself the “odd one out” among a group of speakers that included mainly ex-inmates and veterans, Kessler told the board that while crimes must be punished, White’s inspiring example and mentorship in helping other inmates should be recognized.

“From that sense of responsibility that creates civilization, we also have to have the responsibility to rehabilitate all these guys,” he said.

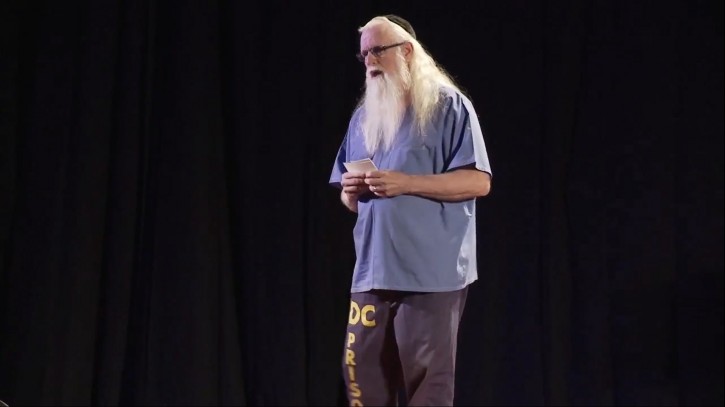

White spoke about the college program’s success during a 2014 TEDx talk at Ironwood. He also started a veterans organizations and held charitable fundraisers while serving his sentence.

“What he’s done, and how he’s turned so many lives around,” said Shad Meshad, the president and founder of the National Veterans Foundation, who has been working on White’s case for decades. “If you could have heard the testimony of these men.”

White was born in London in 1939 or 1940 and adopted by James and Margaret White, a wealthy Jewish couple in Connecticut who later moved to Texas. After three years at Texas A&M, White served 10 years in the Army and the Marines, earning the rank of sergeant, and was decorated for his service.

In 1972, White went to Southern California, where he met his wife, Nancy Napoli, and settled in Sunnymead, near Riverside. According to White, Napoli’s ex-husband began threatening White and Napoli, ignored a restraining order and then molested one of his former stepdaughters. White went to the man’s office and shot him dead. In 1981, he was sentenced to life without parole. White was later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder; his friends say that nowadays his sentence would not have been as severe, because PTSD is more well known.

Although the hearing was a major step, White is not free yet.

Due to the circumstances of his case, the California Supreme Court also must weigh in, but his friends are hopeful. The Board of Parole Hearings, which is comprised of 15 full-time commissioners, was unanimous in its vote, and Lo said the number of people who spoke at the hearing was unusually high. (Wall also spoke there).

Kessler also said that the chief commissioner told him afterward that the number of speakers made a difference.

“Basically she said it was very helpful that all those who came to testify came to testify,” he said.

White has touched many lives during his nearly four decades in the prison system, but if and when he’s released, Meshad said, White will keep doing the same work on the outside: he’s promised to come work for Meshad’s foundation to keep helping the population he’s already helped so much.

“This wasn’t a hard decision,” Lo said. “This is a special case. This is a person with a phenomenal record.”

As reported by Vos Iz Neias