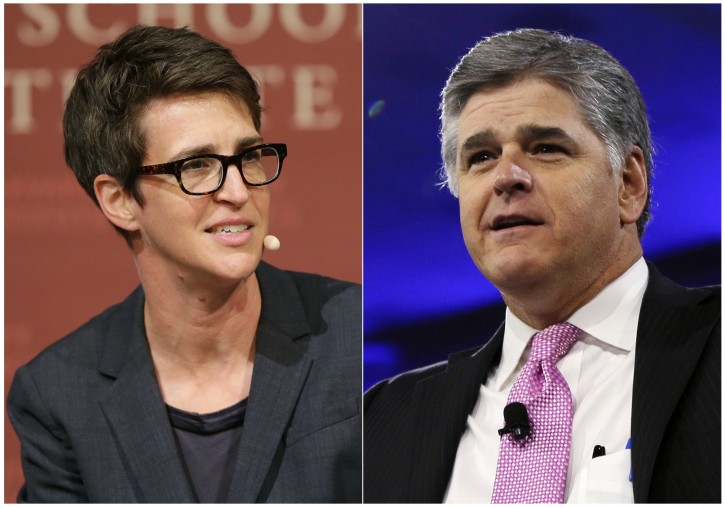

New York – A generation ago, the likes of Walter Cronkite, Peter Jennings and Diane Sawyer were the heroes of television news. Now the biggest stars are arguably Sean Hannity and Rachel Maddow.

Notice the difference? Cronkite, Jennings and Sawyer reported the news. Hannity and Maddow talk about the news, and occasionally make it. But you never doubt how they feel about it.

In a chaotic media landscape, with traditional guideposts stripped away by technology and new business models, the old lines between journalism and commentary are growing ever fuzzier. As President Donald Trump rewrites the rules of engagement to knock the media off stride, he’s found a receptive audience among his supporters for complaints about “fake news” and journalists who are “enemies of the people.”

In such a climate, is it any wonder people seem to be having a hard time distinguishing facts from points of view, and sometimes from outright fiction? It’s a conclusion that is driving anger at the news media as a whole. On Thursday, it produced a coordinated effort by a collection of the nation’s newspapers to hit back at perceptions that they are somehow unpatriotic.

“We don’t have a communications and public sphere that can discern between fact and opinion, between serious journalists and phonies,” says Stephen J.A. Ward, author of 10 books on the media, including the upcoming “Ethical Journalism in a Populist Age.”

Not long ago — think back 30 years — the news business had a certain order to it.

Evening newscasts on ABC, CBS and NBC gave straightforward accounts of the day’s events, and morning shows told you what happened while you slept. Newspapers flourished, with sections clearly marked for news and editorial pages for opinion. The one cable network, in its infancy, followed the play-it-straight rules of the big broadcasters. There was no Internet, no social media feed, no smartphone with headlines flashing.

Today, many newspapers are diminished. People are as likely to find articles through links on social media posted by friends and celebrities. Three TV news channels, two with firmly established points of view, air an endless loop of politically laced talk. There’s no easy escape from a 24-hour-a-day news culture.

The internet’s emergence has made the media far more democratic — for good and ill. There are many more voices to hear. But the loudest ones frequently get the most attention.

“No one can control the flow of information across social media and the internet media,” says George Campbell, a 53-year-old business consultant from Chicago. “This has led to a confusion about fact vs. fake. But mostly, it has resulted in a cash cow for conspiracy makers.”

Let’s not neglect the memorable journalism that the Trump era has produced all across the country. Many newspapers are far from “failing,” as Trump often claims about the scoop-hungry shops at The New York Times and The Washington Post. The number of digital subscribers to the Times has jumped from below 1 million in 2015 to more than 2.4 million now.

The cable networks have turned politics into prime-time entertainment, and it’s been both great for business and polarizing: Fox News Channel (from the right) and MSNBC (from the left) are frequently the most-watched cable networks in the country.

For many years, those network executives did a delicate dance. The stations were news during the day, opinion at night. But with the opinion shows so successful — shouting what you believe tends to “pop” more than facts — it has become harder to suppress those identities. Even when different sides are given, the hours are filled with opinionated people giving their takes.

A recent White House briefing illustrates how the Trump administration has plucked examples from the endless talk feed in its campaign against the media.

When press secretary Sarah Sanders rebuffed CNN reporter Jim Acosta’s attempt to have her renounce Trump’s attacks on the press, she noted that she’s been attacked personally by “the media” more than once, including by CNN.

Both of Sanders’ references had nothing to do with news reporting, and a lot to do with expressions of opinion. One of them, for example, came from an MSNBC appearance by Jennifer Rubin, a Washington Post columnist paid specifically to give her take on things.

But that kind of distinction blurs when it’s decoupled from the newspaper columns and appears in the wild of social media feeds.

“I don’t blame the public for being confused,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, communications professor and director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

In a heated news environment, journalists are left to find descriptions for things they haven’t seen before. CNN’s Anderson Cooper called Trump’s performance in a joint news conference with Russia’s Vladimir Putin “disgraceful” after both leaders left a Helsinki stage this summer. For Cooper, it was a moment of truth-telling. For the president’s supporters, it was a brash embrace of bias.

The Pew Research Center conducted an experiment earlier this year. It presented more than 5,000 adults with five statements of fact and five opinions and asked them to identify which was which. Only 26 percent of respondents correctly identified the five facts, and 35 percent identified the five opinions as such.

The survey suggested that people are in different realities. For instance, 63 percent of Republicans correctly said the statement “Barack Obama was born in the United States” was a fact. Meanwhile, 37 percent of Democrats incorrectly identified the statement “increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour is essential for the health of the U.S. economy” as fact, not opinion.

“Overall, Americans have some ability to separate what is factual from what is opinion,” says Amy Mitchell, Pew’s director of journalism research. “But the gaps across population groups raise caution, especially given all we know about news consumers’ tendency to feel worn out by the amount of news there is these days, and to dip briefly into and out of news rather than engage deeply with it.”

Another contributing factor to confusion is the way news articles often lose their context when spread on Twitter feeds and other social media, Jamieson said. Opinion and news stories live in the same space, sometimes clearly marked, sometimes not.

One Facebook feed, for example, linked to a Los Angeles Times article with the headline, “In a strikingly ignorant tweet, Trump gets almost everything about California wildfires wrong” and gave no indication that it was an opinion piece.

For many people, the editors and news producers who were once media gatekeepers have been replaced by opinionated uncles and old high-school classmates who spend all their time online. Russian trolls harnessed the power of these changes in news consumption before most people realized what was happening.

“The truth,” Ward says, “is no match for emotional untruths.”

News organizations have never been particularly good at either working together or telling the public what it is that they do. The first collective effort by journalists to fight back against Trump’s attacks came this week, when a Boston Globe editor organized newspapers across the country to editorialize against them. That collection promptly was assessed by some as playing into Trump’s hands by suggesting collusion on the part of “mainstream media.”

In an ideal world, Ward says, people would have an opportunity to learn media literacy. And he’d have fewer uneasy cocktail party encounters after he meets someone new and announces that he’s an expert in journalism ethics.

“After they laugh, they talk about some person spouting off on Fox or something,” he says.

He has to explain: That may be some people’s idea of journalism, but it’s not news reporting.

As reported by Vos Iz Neias