Op-ed: Deep down inside, we want to be a bit like the prime minister—to test the limits, to maneuver within the gray area between right and wrong, and to successfully and quickly get away from those trying to catch us.

The State of Israel is a special country, exceptional in almost every aspect. Our many achievements might soon be joined by another record: We could become the first democracy in the 21st century with the dubious honor of sending two prime ministers in a row to jail for corruption.

Ehud Olmert has already served out his sentence and has been released. Benjamin Netanyahu might also find himself, after a lot of wriggling and many delays, in the Maasiyahu Prison. Our wheels of justice turn very slowly when it comes to strong, brilliant and influential people, but at the end of the day, they usually grind exceedingly fine.

Why is this happening to us? Are we just a particularly corrupt country, which produces particularly corrupt politicians? I don’t think so. In most global corruption indices, we make it to the middle of the democratic countries list. And our situation is much better than countries like Turkey, Russia, Iran, all the Arab states, and almost all Third-World and Fourth-World countries. Granted, not everything is wonderful here, but we’re not Sodom and Gomorrah.

I think our problem, which is the reason many people in Israel’s political echelon are afflicted with corruption, is different: We are people with no borders.

Where do we draw the line?

We are literally borderless. Israel is the only country in the world which has been persistently refusing, for more than 50 years now, to outline its borders, even in its official maps. Remind me, where does Israel end? Along the Jordan River? Or possibly on the Green Line, may its memory be blessed? Or along the separation barrier in Judea and Samaria? It’s unclear, and not incidentally.

We don’t like to know, and we mainly don’t want to say, where we start and where we end. We don’t like that question. And we really don’t like borders. When Israelis see a border, they immediately start thinking about how to expand it and how to cross it. Ask the Egyptians, the Lebanese, the Syrians, the Palestinians and everyone whose bad luck got them involved in an armed conflict with us. It’s an experience I wouldn’t recommend to anyone.

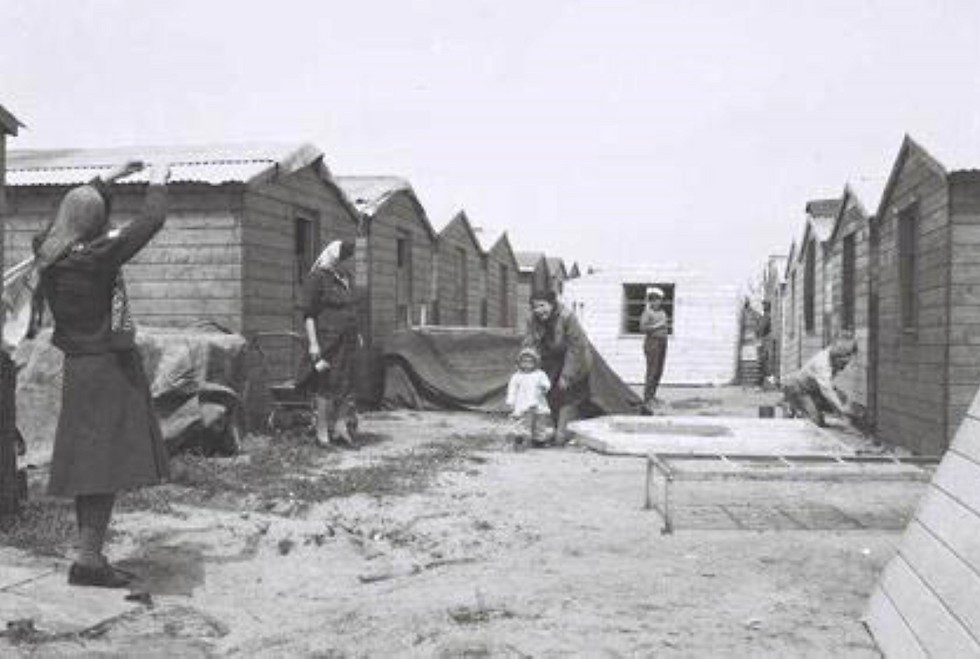

Where does it come from, this thing with our borderlessness? I don’t know, but I have a hypothesis. The State of Israel was established by people who rebelled against their parents and went against the laws and rules of the societies they were born in. They came here to start over, their own way. Also the immigrants who arrived after the state’s establishment, from Islamic countries and from Europe, left the parental authority in their homelands.

The new Sabra were ashamed of their parents’ ghetto mentality. Most importantly, they discounted them and they discounted their rules and borders. And so, Israel raised millions of people who are great at testing limits and love seeing what can be done without getting caught.

In my opinion, there are two reasons why half of Israelis still support Netanyahu, although he has pink champagne on his hands: First, it’s unclear to us where a quid-pro-quo relationship between acquaintances and friends ends and where naked corruption begins.

In a country where we are all brothers and buddies, where a friend brings a friend, it’s hard to know where exactly to draw the line between PR and lobbyist activity—which may stink but is nevertheless legal—and the criminal corruption in the meeting of government, capital and the press.

Most of the people in Israel today hate the Supreme Court, and our quick politicians are finding it easy to incite against it and harass it. Why? In my opinion, it’s because the honorable court speaks a foreign language, rather than local Hebrew. The words “rule of law” simply don’t appeal to the majority of voters here, and Netanyahu understands that very well.

Undermining and rebellious elements

Which brings me to the second reason I believe Netanyahu will keep enjoying wide public support, even behind bars: Deep down inside, we want to be a bit like him. Many people here like to test the limits, to maneuver within the gray area between right and wrong, to stretch the possible to the limit and to successfully and quickly get away from those trying to catch them.

Winston Churchill, Netanyahu’s hero, said: “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” From personal experience, I know he was right. In fact, we all do. Later this week, we’ll all sit around the Passover Seder table and sing: “Not only one has risen against us to annihilate us, but in every generation (our enemies) stand up against us to annihilate us.” We’ll sing, think and perhaps say out loud: “Isn’t it great that they tried and failed? We showed them, didn’t we?”

There are undermining and rebellious elements both in Judaism and in the Jews. It’s a national trait, which has been following us like a shadow for 3,500 years now. Since Abraham got into an argument with God over the number of righteous people needed to save Sodom, we like to see what can be achieved through a combination of chutzpah, initiative, craftiness and a willingness to test the limits.

The Jewish and Israeli inclination to cross lines and find ways around restrictions holds advantages too: Part of what makes the IDF such an efficient and dangerous army to its enemies is this spirit, which constitutes part of the education and socialization of all our commanders and fighters. Phrases like “pursuing contact,” “exploiting success” and “that’s what we have, and with that we’ll win” are not only clichés, but also a mentality which leads to resourcefulness, improvisation, thinking on one’s feet, and eventually victory.

And it’s not only in the army. Chutzpah, initiative, thinking outside the box and a desire to test limits and do the impossible are part of the raw materials of many of the initiatives and inventions that have developed here, turning Israel into the startup nation we take so much pride in.

In conclusion, can we have it both ways? Can we be brave, cheeky entrepreneurs without being corrupt, hedonist criminals? I think so. In the 70 years of the State of Israel, we have had several prime ministers, from the Right and from the Left, who were a nice, personal example of such conduct.

I’m talking about David Ben-Gurion and Menachem Begin, about Levi Eshkol and Yitzhak Shamir. It’s not a pie in the sky, and it’s no dream. It will take time, but after the Netanyahu affair is over and behind us, we may succeed in doing what we’re so good at: Starting over.

As reported by Ynetnews