JTA’s Europe correspondent looks back at his mother’s feminist teachings and wonders how he can equip his daughter to cope in a world that’s unfair to women

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — When the obstetrician told us last fall that we were expecting a girl, I was overcome with a mix of apprehension and what I can only describe as disappointment — followed immediately by shame.

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — When the obstetrician told us last fall that we were expecting a girl, I was overcome with a mix of apprehension and what I can only describe as disappointment — followed immediately by shame.

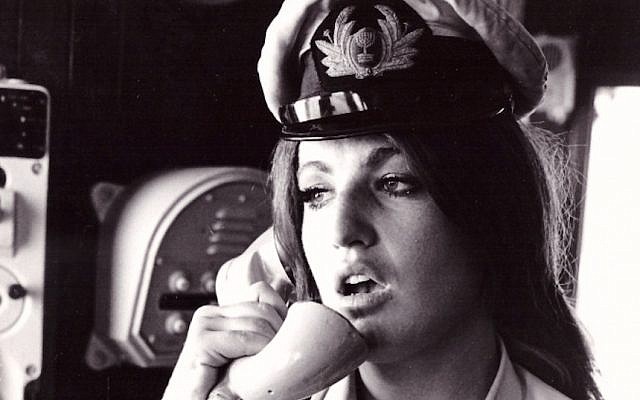

I was horrified by my initial reactions. I felt guilty as I remembered my late mother, Abigail Bechler, who was a feminist trailblazer. Born and raised in Israel, she had sailed the Seven Seas in the 1960s as the first female deck officer of ZIM, the Israeli merchant marine. My mom, who died in 2008 at the age of 60, also taught me the essentials of household electrical repairs, the efficiency of defensive violence and a couple of languages.

It took me several months, amid the soul searching that goes on ahead of Yom Kippur, to work out how, despite her feminist education, I could dread the prospect of parenting a girl. (After all, I was more than fine with having a boy two years ago.)

Ahead of the Jewish Day of Atonement, I recognize now that my apprehension was the result of an unhelpful combination of emotions. First, there was my fear of the potential difficulties of raising a girl in a world that is unfair to women. And that feeling was exacerbated by my insecurity in my ability to give her the tools to cope with it.

Moreover, I think my insecurity was amplified by realities that I’ve observed as a reporter who is often on the road: I’ve witnessed growing religious fanaticism in developing countries alongside growing chauvinism in the West. And from what I’ve seen, I think these developments make this world more unfair to women than the one my mother inhabited.

My work often takes me to remote places where women are regarded as property — or worse.

In Dagestan, a predominantly Muslim state of the Russian Federation, I met women, including Jewish ones, who were living under a curfew. They met me in secrecy not because I’m a journalist but because I’m a man. One of them, a forward-thinking university student, told me she would be ostracized as a “whore” if anyone saw us drinking coffee together.

I was shocked to learn of the Dagestani tradition of bride abductions — a part of courtship in which men, including Jews, kidnap their chosen ones violently on the street. In nearby Azerbaijan, I fumed at how my wife, who joined me on a reporting trip, was confined to what amounted to house arrest in the hotel by local policemen who shadowed her and harassed her whenever she dared leave the lobby unchaperoned. And I was astonished to see a synagogue in the north Azerbaijani town of Krasnaya Sloboda that banned women from entering.

In Senegal, street thugs harassed my wife in broad daylight right in front of me. It was part of a technique in which they targeted women in order to pickpocket whomever came to their defense. (It worked: They took my cellphone in Dakar.)

In Uzbekistan, I spent Shabbat with a Jewish businesswoman whose neighbors smashed her car because they were upset to see a woman driving.

In Turkey, I was exposed to the realities of life for Syrian immigrants whose husbands do not allow them to attend an occupational training course because the class was coed. This problem prompted a Jewish group from the United Kingdom to set up a special women-only community center in the Turkish city of Gazyantep.

In India, I learned that the absence of indoor toilets exposes women to the risk of rape. Many reported rapes there occur when women venture into wooded or open areas, often after dark, to relieve themselves.

And in Burundi, I broke bread with a 70-year-old man who boasted to me about the beauty of his second wife, a girl not older than 16 who had already given him one child.

Being optimistic about women’s rights came much easier to me before I witnessed all those things. Maybe because I was younger then, or maybe because I was lucky to grow up in the West during the 1980s.

In my native Israel, the Knesset in 1988 passed the Equal Employment Opportunity act – the country’s first major piece of legislation on women’s rights since 1951. It made discriminating against employees or candidates punishable and illegal. It ushered in the Equal Pay act of 1996, which addressed, but did not solve, salary gaps between genders, as well as legislation against sexual harassment.

In the Israel Defense Forces, I served in elite units both with and under female soldiers and officers who, in the difficult days of the second intifada and the Second Lebanon War, matched and outperformed men. And my friends who served in the Israeli Air Force reported back proudly of the inspiring progress of the first female cadet, Roni Zuckerman, who enlisted with us in the summer of 1999 to eventually become Israel’s first fighter pilot.

I would like to tell myself that when it comes to women’s rights, the West and the Third World – and particularly the Muslim world – occupy different realities. That would be a comforting thought that agrees with the feminist education my mother gave me.

Except over the past decade, I have seen chauvinism and misogyny making a comeback in Western societies, too.

In the Netherlands, harassment and catcalling on the street made it impossible for my wife to wear knee-length skirts or even a dress in the predominantly Muslim neighborhood of The Hague where we used to live. We left when the harassment began happening regardless of how she dressed, presumably because she looks European. Meanwhile, the devoutly Christian SGP party has suffered no loss at the ballots – it has three seats out of 150 – for its policy of discrimination against women.

In Marseille, when a graduation ceremony this summer of a Jewish Bible study group featured women reading from the Torah, it provoked a rabbinical edict, protests, threats and insults.

And in Israel, the IDF is suddenly facing repeated walkouts by devout soldiers who disobey orders at ceremonies and cultural events because they feel it is immoral to listen to women sing. Meanwhile, the army is cautiously planning to begin training female recruits to serve in the armored corps — amid vocal opposition to the prospect by religious soldiers and commanders, and some lawmakers, who say women have no place inside a tank.

In the United States, there is also reason for pessimism: The fight for women’s right to have an abortion has only become more complicated, not to mention the recent election as president of a man who has spoken of women in the most vulgar and demeaning ways.

Of course, in spite of all this, there is progress being made on women’s rights issues — not only in the West but the Third World and in Muslim societies. Some examples include the formation of France’s most egalitarian government under President Emmanuel Macron, and the hiring of female clergy in British, Israeli and American Orthodox synagogues. And although women’s rights have taken major hits in Muslim countries in recent years, there are signs of reform. In Saudi Arabia, for example, where women are not allowed to drive, there’s been a relaxing of rules requiring women to get a male guardian’s permission to obtain various government services.

Yet for the first time in decades, I feel frightened by the signs of regression.

It seems to me that a dark undercurrent is swelling under the wave of progress that took my mother to sea in the 1960s. Back then, Iranian and Afghani women wore jeans. I know because my mom took photos of them.

At the obstetrician’s office, I think I must have felt sorry for my daughter. As a girl — and later a woman — she will have to negotiate straits being narrowed by oppressive zealots on both sides, as even the progressive Dutch society in which she’s growing up is finding itself squeezed between modernity and its antitheses.

On the plus side, now that she’s here, that feeling of pity has long given way to joy.

My daughter, now 4 months old, is a plump and smiley baby who enjoys my anguished grimaces as she pulls mercilessly on my beard. And my sense of helplessness has been replaced by a newfound determination to prepare her for the challenges that I know await her.

The essentials of household electrical repairs are as good a place as any to start.

As reported by The Times of Israel