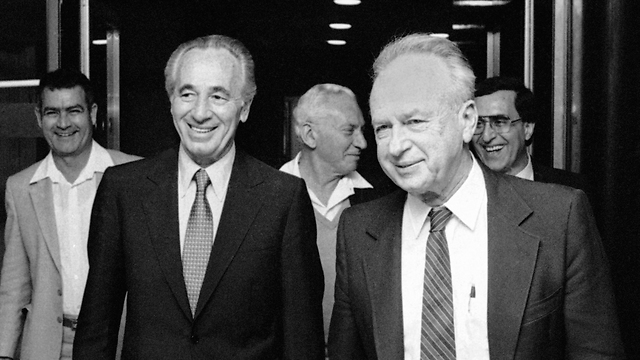

On one side, a decorated IDF chief of staff; on the other, an experienced politician; from day one to that fateful moment when three shots were fired following a peace rally in Tel Aviv, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres were bitter rivals.

“That man ruined my life,” Shimon Peres yelled, “I’ve been working for him for over 16 years, and he doesn’t say ‘thank you’ to me. He’s crazy, and now he wants to hijack my ceremony. What has he done on this matter? Nothing. In that case, I’m not going to Washington. I prefer to resign my position as foreign minister. I’ll leave him the stage, that’ll please him. I’m tired of hearing about Rabin believing me, not believing me. I treated Rabin like a king, and he returns the favor with insults.”

Saturday morning, September 1993, three days ahead of the official signing of the agreement between Israel and the PLO on the White House lawn. An historic moment for the state of Israel, and no less so for its then-minister of foreign affairs, Shimon Peres. Interestingly, it seemed like it was easier to create trust between the Israelis and Palestinians than between Peres and his prime minister.

We were sitting in Shimon Peres’s apartment, conducting an interview in which Peres wanted to speak of his crucial role in bringing about the upcoming agreement. I navigated, I did this and that, and I will represent Israel at the signing ceremony. A short while later, his office received a telephone call in which he was told Rabin has decided to go to Washington, DC, himself and lead the Israeli delegation at the signing. Peres was apoplectic. What he then said about Rabin was first published this weekend in Yedioth Ahronoth (Ynet’s Hebrew-language newspaper partner) and here—and this is a censored version.

For hours after that, Giora Eini—the two’s regular mediator—attempted to calm things down. Peres, enraged, really did consider not travelling to the ceremony. Only after a number of conversations did he cool down and agree to fly with Rabin to the US, where the two of them put on a façade of perfect harmony.

Peres and Rabin had a murky relationship from start to finish. Despite his clean-cut image, Rabin wasn’t any less devious a party here. For a while, from the moment the peace accords were signed on, the two stopped squabbling over credit. Peres didn’t undermine Rabin, and Rabin didn’t speak out against Peres—but the stories about supposed closeness between the two weren’t based on much solid evidence.

Rabin’s personal opinion of Peres didn’t change—”that clerk for whom the only (projectiles) that flew by his ears were ping-pong balls,” he used to say mockingly of his fellow Nobel Peace Prize recipient. Even in the afternoon hours of that same rotten day, November 4, 1995, Eini had to mediate between the two. There are those who say Rabin even considered not attending that peace rally, at which he was murdered, before finally agreeing to come.

The gates of hell open

“More excessive sabotage and nerve that these are hard to imagine… I reject Peres in essence and see his rise as a highly malignant moral rot—I will (powerfully mourn) the state if I see him sitting on a minister’s seat in Israel.” –The diary of Moshe Sharett, Israel’s second prime minister.

For his entire public service tenure, Peres was a better statesman than politician. The clashed between him and his party’s members were often only halted when the other person passed away. Rabin, Moshe Dayan, and others saw his political rise as a personal insult, as they had earned their position through IDF service, while Peres never served in the military.

Peres himself wanted to prove that he could fill any role. When he was appointed director of the Ministry of Defense under Minister Pinhas Lavon, the relationship between them quickly deteriorated, reaching their lowest point with the Lavon Affair (a 1954 false flag operation in which Israel attempted to conduct several bombing via agents placing explosive devices in Egyptian, American, and British-owned targets in Egypt, blaming the Muslim Brotherhood and other local extremist groups. The aim was to induce the British to keep their forces in the area of the Suez Canal. Lavon was forced to resign his position when the facts came to light). Peres testified against his old boss, calling him an irresponsible thrill-seeker . When Lavon handed PM Sharett his resignation, he referred to Peres as his mortal enemy.

When he was first elected to the Knesset in 1959, Peres was appointed deputy minister of defense. He would fly around Europe taking different meetings, sponsored by his mentor, David Ben-Gurion. Sometimes, he didn’t bother updating Foreign Minister Golda Meir about these trips. “I gave the condition that Peres be removed from any sensitive security position as a prerequisite for my membership in the government,” the future prime minister said.

The first head-to-head between Peres and Rabin took place on April 22, 1974. Peres was experienced in Ma’arach (one of the incarnations of the Israeli Labor Party) party politics and Rabin was sent in at the request of old party veterans. He came into the party still holding on to the halo of the Six Day War (during which he acted as IDF Chief of Staff), and was not stained by the government’s failures during the Yom Kippur War (as he was not in office at the time). Peres, to him, was part of the old order

At first, the two agreed that the loser would accept the winner; very quickly, however, their party chair campaign began to turn ugly, with mutual smears that culminated in the publication of the claim that Rabin collapsed on the eve of the Six Day War. Rabin was certain Peres was behind that last one, and when he prevailed, the gates of hell opened.

“The solid base assumption upon which this insatiable underminer, Shimon Peres, has based his delusion was (the idea) that between him and the prime minister position stood no obstacle save for Yitzhak Rabin… It would be enough for him, then, to push me out of his way and swear the oath of allegiance as prime minister over the high podium of the Knesset,” Rabin said in a speech.

In his 1979 book, Service Notebook, was published in 1979 and expressed the severe contempt he felt for Peres. It immediately became a best-seller, used by Likud leaders—especially then-Prime Minister Menachem Begin—as a tool to skewer Rabin and their mutual rival.

Rabin was paranoid about everything that had to do with Peres. Even today, after nearly 40 years, I couldn’t say who was behind the leaks about Rabin’s close environment, but as a young journalist I was shocked to find out that the Prime Minister’s Office was occupied by a person who was sure Peres’ entire essence in life was to harm him.

“His feverish desire to concur the prime minister position knew no bounds, and almost everything was permissible: Leaks, constant undermining of the prime minister’s standing, and the shaking of the entire government’s standing,” Rabin wrote, “An all of this based on the old Bolshevik notion that says the worse things are (for everyone else)—the better things will be for Peres’ people and their leader.”

“I didn’t think Peres was fit for the role of defense minister, since he never served in the IDF,” Rabin continued, “I accepted him for the role with a heavy heart. It was a mistake. I knew I’d be sorry about it and that I’d pay the full price.”

As defense minister, Pres opened his door to settler leaders, made sure to supply the permits for the establishment of institutions near Ramallah—which quickly turned into the settlement of Ofra—and enthusiastically supported the implementation of ideas held by the people of Gush Emunim. Do the mountains of Samaria not rise as high as the Golan Heights, he was said to have asked.

This led to one of the most severe conflicts between Peres and Rabin. The PM rejected the idea of Jewish settlements in areas with dense Palestinian populations. His office instructed the defense establishment to prevent a group of settlers who found an abandoned train station in Sebastia from occupying the spot, located about ten kilometers northwest of Nablus.

Peres ignored these instructions, and the settlement of Elon Moreh was born. Champagne bottles were uncorked in the defense minister’s office, and the PM’s associates responded by saying, “Peres and his advisers were the Trojan horses that allowed Gush Emunim to entrench itself in the heart of Samaria.” It’s not at all certain that “Trojan horses” is the correct term, but I spent some time with the settlers in the field back then, and despite Rabin’s instructions, they did not worry for a moment about the IDF being ordered to evict them. The direct line to the minister of defense’s office gave them the confidence to know that any temporary land takeover on their part would lead to a permanent settlement. And so it was.

In March 1976 the relationship between the two derailed further, with Peres allowing municipal election to take place in the territories. The more extremist candidates won, and Rabin claimed, “The government made a mistake and took steps that did not add to its prestige.” By “the government” he meant Peres. At the height of the crisis, the two would only communicate through an internal group of party members, and Peres was openly contemplating Rabin’s ouster.

Price of The Dirty Trick

“It was an especially difficult fall for me… I was of a bitter soul. I felt I enjoyed the faith of my party, but I was distanced from leadership just as local and global developments created a chance for peace.” –Shimon Peres, after losing a primary election to Rabin in the early 1990s. Quoted from Shimon Peres: The Biography (2007), by Michael Bar Zohar.

Another hard clash between these the pair came in 1990. Peres planned to take over the government. Following 1988 Knesset elections, a unity government was established. In 1990, Peres planned to overthrow PM Yitzhak Shamir by forming a narrow coalition of ultra-Orthodox and left-wing factions. Among the reason for the move were disagreements he had with Shamir regarding the peace process, and the American government’s support of positions closer to those of Peres.

Peres managed to disperse the government via a Knesset vote, but failed to establish a new government headed by himself, due mainly to ultra-Orthodox rabbis, who had great (sometimes direct) influence over ultra-Orthodox MKs, some of whom forbade participation in such a government for various reasons. In the end, Shamir formed a new government following the dissolution of the old one. Rabin did not like Peres’s maneuver, and coined its nickname, The Dirty Trick, which stuck.

Peres’s loss to Rabin in the 1992 primary elections—the first open primary in the Israeli Labor party—hurt him. And still, he accepted the role of foreign minister. They once again worked together and separately, trying to move Israel toward secure borders and a permanent agreement with the Palestinians.

Rabin forbade him from any negotiation activities, but Peres did not give up. He began to look for alternate channels for handling the peace process, and was eventually allowed to run negotiations over economic cooperation in the region. Peres used this crack in the door and maneuvered himself into direct talks with PLO representatives.

Rabin didn’t believe that the probing by Peres’s people—Dr. Yair Hirschfeld and Dr. Ron Pundak, and later Foreign Ministry director Uri Savir—would lead to anything significant. In mid-March, a senior official told me of talks taking place in Scandinavia. Most likely, the official was leaking information in an attempt to blow up Peres’s efforts. I called Rabin. “I know of this,” he said, “It’s not serious; leave it alone.”

Recently, then-Mossad Director Shabtai Shavit told me about what happened behind the scenes. “In the beginning of March I came to Rabin for the meeting we had each week,” he said, “I reported to him that our sources found out that several of the PLO leaders were meeting with officials from Israel at a Norwegian government guest house near Oslo. Rabin looked at me, said ‘I’ve heard,’ and didn’t add anything. Several months later I came to Rabin again and told him about the movements of the senior members from Tunis to Oslo, and the talks with the Israelis. This time, Rabin said, ‘I know of this and ask that you not deal with it anymore.'”

This time, it turned out, Peres did not work alone, and was informing Rabin, who probably hoped nothing would come of it. Only when the negotiations he was conducting with Syrian officials fell through did Rabin give the green light to seriously go forward with the Palestinians. Eventually, it led to that famous ceremony on the lawns of the White House. In retrospect, Peres and Rabin made a mistake, especially regarding Yasser Arafat, who refused to say farewell to his arms and act like a peace-seeking leader.

And then came the terror attacks, and the protests by right-wingers, and the extremist right-winger Yigal Amor, who assassinated Rabin. Rabin was left in the public consciousness as a soldier, a commander, and a statesperson whose speech was direct—in ways that weren’t always easy to digest. Peres will most likely be remembered as a man of vision and dreams, a statesperson who never tired of searching for solutions to unsolvable problems. And also, as an unrelenting politician.

“We made a good pair,” Peres would later claim of his relationship with Rabin. “A good pair. It was easier for me to be Rabin’s partner that it was for him to be mine, since I tend to be tempted, he’s more realistic. In everything: Believing Arafat, not believing, believing friends… I prefer to fail because I’m innocent and not because I’m cynical or sober.” Rabin described things differently, and said he simple didn’t trust Peres. At all.

In death as in life, it seems Peres and Rabin are destined to disagree.

As reported by Ynetnews