Staten Island, NY – New York City might never tell the public if the police officer at the center of the Eric Garner chokehold death case is disciplined, the mayor and police commissioner indicated this week after reaching a new interpretation of a 40-year-old state civil rights law.

The New York Police Department recently ended a longstanding practice of letting reporters see a rundown of disciplinary actions, saying officials had concluded it violated the law.

Asked Tuesday whether the new stance would apply to the officer who put his arm around Garner’s neck in a case that helped fuel the Black Lives Matter movement, Democratic Mayor Bill de Blasio said officials “have to honor state law.”

Citing the mayor’s comments, Police Commissioner William Bratton said Wednesday the results of any potential disciplinary trial against Officer Daniel Pantaleo “would not be publicly available,” though he predicted they probably would eventually “get out” somehow.

Any disciplinary moves won’t happen until federal prosecutors decide whether to bring civil rights charges against Pantaleo, whom a state grand jury declined to indict. But the discussion is illuminating open-government advocates’ concerns about the NYPD’s new legal position on disciplinary records.

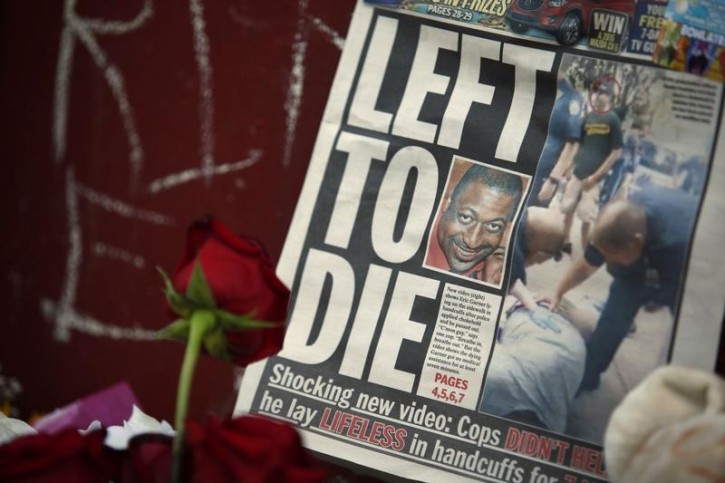

Caught partly on video, Garner’s fatal 2014 encounter with Pantaleo made “I can’t breathe!” a rallying cry in protests and national debate over policing, brutality and race. Garner, who had refused to be handcuffed as police tried to arrest him on charges of selling loose cigarettes, was black; Pantaleo is white.

The medical examiner ruled Garner’s death a homicide caused partly by a chokehold, a maneuver banned under NYPD policy. Pantaleo’s lawyer, Stuart London, said the officer used a permissible takedown move, not a chokehold, and argued Garner’s poor health was the main reason for his death.

London declined Wednesday to comment on the police department’s new position on disciplinary records, first reported by the Daily News. The Garner family’s lawyer didn’t immediately respond to a message seeking comment.

Bratton said the change came after a recent public records request prompted the department to re-examine a 1976 New York state law. It shields records “used to evaluate performance toward continued employment or promotion” of police, firefighters and correction officers, unless employees release them or a judge orders it.

Open-government advocates have long questioned the law.

“The public employees who have the most power over people’s lives are the least accountable due to (the law) — it should be the reverse,” said Robert Freeman, executive director of the New York State Committee on Open Government.

Bratton said he’d support releasing disciplinary actions if the law allowed it.

But the New York Civil Liberties Union disagrees with the department’s new reading of the law and questions its impetus, associate legal director Christopher Dunn said.

“What we really think is happening here is that the city is taking an increasingly aggressive position attempting to keep information about police discipline away from the public,” he said. “And we think that’s wrong.”

As reported by Vos Iz Neias