Op-ed: The public’s sentiment towards IDF soldiers has not only obscured people’s perspective on the importance of civilian life, but has blinded them to the difference between soldiers who act nobly and those who act questionably.

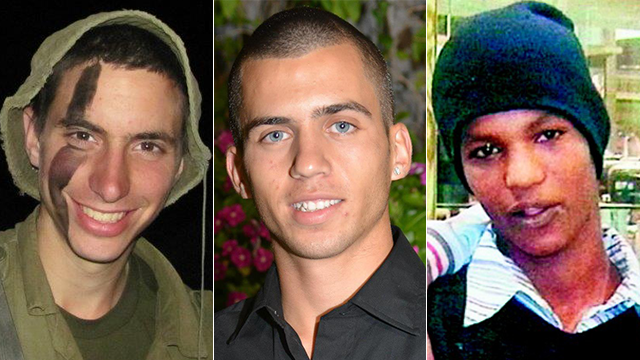

What separates Yehuda Haisraeli, one of the most severely wounded soldiers from Operation Protective Edge, and Elor Azaria, the Hebron soldier? It seems fairly clear: One of them is a resident of the settlement of Ofra, a father of two who was critically wounded in battle. The other is a resident of Ramla, a common soldier who was patrolling one of the most intense areas of the recent terrorism wave and shot a neutralized terrorist.

But the similarities are also there. Both of these men received practically unprecedented help in the form of donations from the public, via crowdfunding website HeadStart.co.il., due to a widespread feeling that the state had neglected them.

Yehuda received NIS 1.5 million in just one day and a half so that he’d be able to make his home handicap accessible. The Defense Ministry refused to provide the funds for the appropriate installments, claiming the home was illegally built. Elor received over NIS 500,000 in 12 hours (and it’s still coming in), for his private legal defense. Members of the public apparently felt he was a scapegoat.

The public’s actions in helping these two stem from the unquestioned assumption that any soldier, no matter who he may be, is above any civilian in Israel. After all, these soldiers are “everyone’s boys,” and we have long since lost all perspective on how we treat them: Instead of seeing them as being our protectors, some Israelis feel the need to protect our soldiers and mollycoddle them.

This phenomenon is present when discussing another complex public issue: the return of the remains of fallen soldiers, held by Hamas. While the discussion about the return of the remains of Hadar Goldin and Oron Shaul, who fell in Protective Edge, is an active part of the public debate, civilian Avera Mengistu, who is alive and in Hamas captivity, atracts a minimal public outcry. There’s a clear hierarchy, which states that the bodies of two dead soldiers are more important than a psychologically damaged, but living, civilian.

Furthermore, the public’s generosity towards Haisraeli and Azaria says something about the wide gap separating the state and its people. The feeling that the state has abandoned its soldiers – either by not helping make a man’s home accessible to him, or by not providing him with expensive legal council – is part of the same pattern. And when the people feel that a soldier has been abandoned, they open up their wallets.

I wonder how we’ve reached a state in which we hurry to help someone just because of their status and not their actions. When was the moral compass – which instructs us to look at the details of each case, and learn to differentiate between those who were wounded in battle and those whose life is full of suffering, and those who are suspected of criminal actions after violating explicit orders? Lost?

When did the “our boy” motto start to mean that all soldiers are angels? And how is it that the IDF is the most beloved institution in Israel, while its leaders are deeply hated?

It seems that a complex discussion about this isn’t even an option. The principle line separating what’s wrong (shooting a neutralized terrorist) and what’s proper (fighting the enemy, even at the cost of your own life) has been blurred beyond recognition.

Those who raise funds for Azaria emphasize the idea that the money left over will be used to help the next soldiers who may fall victim to the military legal system. And perhaps this is the worst sign of all: the realization that Azaria’s case may not be a one-time thing, despite its severity, and the realization that other soldiers may do as they see fit, even if that means violating clear orders. After all, what’s the worst that could happen to them? They’re “our boys.”

As reported by Ynetnews