Analysis: New procedures for prisoner exchange negotiations have already been recommended by a national commission—five years ago. And yet, Israel seems like it may soon be dragged into another publicly contentious prisoner exchange with Hamas.

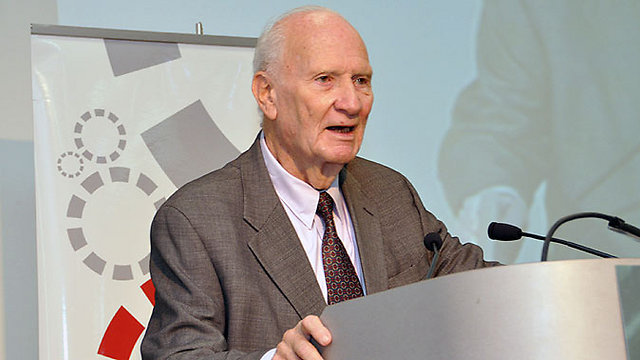

Had the Israel government accepted the recommendations of the 2011 captives redemption commission, those who negotiate with Hamas these days wouldn’t have the authority to offer it more than 6–10 live Palestinian prisoners in return for the Israelis they hold. That’s more or less the “price” recommended by the commission, headed by Supreme Court President Emeritus Meir Shamgar, for two soldiers’ bodies and two live Israelis.

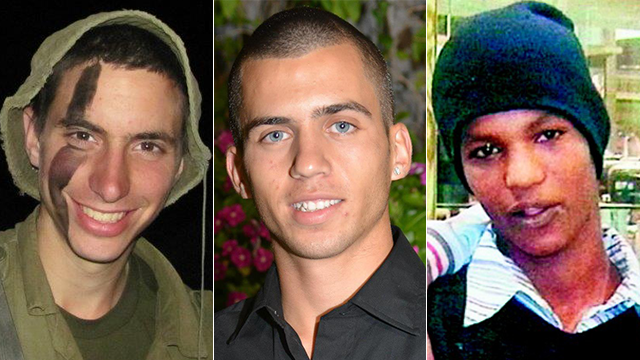

Hamas’s published demands, which indicate that it is interested in recreating the Gilad Shalit deal, symbolize the beginning of the Israeli public’s fight with its government over the return of captives—almost without regard to the price.

The Jibril Agreement in 1985 showed that Israeli society had a hard time accepting losses, captives, and missing persons. It doubted its leaders’ judgment and negotiated with them over “the price of warfare.” The Shalit affair was the apex of this phenomenon, leading the political leadership to understand that it had no room to maneuver in the face of public pressure.

Then-Defense Minister Ehud Barak took initiative in establishing the Shamgar Commission, which was to recommend a mechanism that would give back maneuvering space to the military-judicial-political ranks in these situations. The commission’s members—among them Shamgar himself, Prof. Asa Kasher and IDF Maj. Gen. (res.) Amos Yaron—came to several conclusions whose goal was to allow the professionals handling the negotiations and the country’s leaders to make rational decisions that are not unduly influenced by public sentiment and are aimed at serving the national interest.

The first conclusion reached by the commission is that negotiations and operative recommendations should be handled by a professional and covert body in the security community, which would report to the minister of defense. Once a soldier or civilian is captured or kidnapped, a standard and covert series of steps should be taken, just as is done when in other types of security-related incidents.

The presence of an Israeli in captivity in enemy territory, the commission said, demands an organized and secretive process. The professionals who should handle the negotiation for a prisoner exchange would come from all relevant bodies and areas of expertise, and should, according to the commission, present their recommendations to the defense minister alone. The prime minister would be disengaged from the process. That way, he would be less subject to pressure from the loved ones of Israeli captives.

The Shamgar Commission looked for a way to create a wall between government ranks and the public outcries, especially when negotiations are ongoing and the enemy starts to disseminate information to influence the civilian population’s mindset. This is where the commission recommended a series of mechanisms that would prevent the prime minister—or a small group of high-ranking government officials—from altering the professional team’s recommendations. If the PM and his fellow government members desire to appease the public and go against the commission’s recommendation, they would not be able to do so without going through certain legal or regulatory checks.

If the PM wants go give back 1,000 prisoners for one Israeli, in contrast to the recommendations of the professional team, he would have to bring the proposal to a government vote. If a majority of government members do not vote for his proposal, it would be rejected.

The second check would be the Knesset. The PM would have to bring the changes to the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee and have it approved by a majority of members. If the Knesset were to vote on the proposal, it would have to be approved by at least a 90-MK majority (75 percent of the Knesset) in order to pass.

The bottom line is this: The price Israel pays for captives has to be widely agreed upon.

The Shamgar Commission recommended maximum rates for the exchange of living captives and the exchange of bodies. A body, for example, would not be exchanged for more than one Palestinian prisoner. Why, five years after the commission concluded its proceedings, is the prime minister still refusing to accept its conclusions?

As reported by Ynetnews