Analysis: Testimonies from the commandos who fought in Entebbe shed new light on the great mystery surrounding the operation.

The book “Operation Yonatan in the First Person” was written to fill a strange vacancy.

To this day, there hasn’t been an official investigation of Sayeret Matkal’s operation in Entebbe. The commandos, intelligence officers, and the operations and logistics personnel have never been asked to tell their own version of events or to officially provide one for the record. After Yoni Netanyahu was killed, it was important to his replacement, Amiram Levin, to show that it was still business as usual for the Special Forces unit. And with the commander’s funeral and the next important operation planned for a few months afterwards, there was no time to conduct a proper in-depth investigation of the operation that has turned into the elite unit’s trademark.

The IDF General Staff’s History Department did issue a document in November 1977 based on a partial investigation of the operation, but it is plagued with errors and lacks important information.

That no official investigation has ever been conducted is particularly strange in light of the fact that Operation Thunderbolt—the code name given to the rescue mission—is certainly not an operation the IDF should feel ashamed of. This is one of the most important commando operations in history. Several other operations were inspired by it—some successful (GSG-9 operation to rescue the Lufthansa Flight 181 hostages in Mogadishu), and some less so (the American attempt to rescue the US embassy hostages in Iran in 1980)—but there hasn’t been an operation quite like Entebbe. “Thunderbolt” is also probably the commando operation that has been covered the most in books, articles and movies.

The special thing about “Operation Yonatan in the First Person,” excerpts of which are published for the first time in this special project, is that for the first time, commandos from Sayeret Matkal have each written their own version of events, as they would do in an official investigation, without any external influences or censorship.

The book helps solve the big mystery surrounding the operation: How did it succeed? How did it come to be that something that looked “strange and completely unlikely” or a “Hollywood fantasy” (according to Sayeret Matkal commandos) several days before, turned into such an awe-inspiring success? How did an operation in such a far-away and hostile place, which would normally require months and at times years to plan, take shape in only 48 hours?

The answers to these questions, as the testimonies in the book indicate, are a combination of several factors and reasons.

First: the human factor. There is no doubt that many things could have gone wrong, leading the operation to end in disaster. On the other hand, the fact that Sayeret Matkal that was tasked with this complicated challenge—bringing its experience, the tools at its disposal, and its excellent personnel—reduced the margin of error to a minimum.

In one of our conversations, Yiftach Reicher-Atir—at the time the unit’s deputy commander, who headed the force that stormed the first floor of the terminal where the Ugandan soldiers were (and also the editor of the book)—compared Sayeret Matkal to an upside-down pyramid. It is an elite unit with quality personnel at its disposal, and “when all of the state’s resources are focused on a specific day, hour, minute… the pyramid’s top is pointing to the target, and everything else is pushing from above. In the end, the pyramid’s top will pierce the target, no question about it.” Reicher-Atir was talking about the assassination of Abu Jihad (Khalil al-Wazir, the co-founder of Fatah who was killed by the unit in Tunis in 1988), but his words apply to the Entebbe Operation as well.

Second: the element of surprise. Israel was surprised by Wadie Haddad’s ability to hijack a plane and fly it somewhere as far as Uganda. But surprise also worked in the opposite direction. Because of the great distance from Israel, it appeared that the hijackers and Ugandan soldiers didn’t imagine Israel would even consider a rescue operation. In other operations, inside Israel, when the Sayeret was operating under much more favorable conditions, it sometimes failed. The October 1994 raid on the house where IDF soldier Nachshon Wachsman was kept ended completely different, even though it was conducted by the same unit, under the same prime minister. This was, among other things, because the kidnappers were far more vigilant.

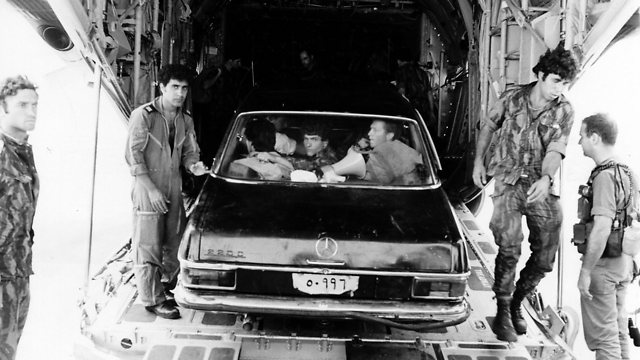

Third: the intelligence. The unit’s intelligence officer, Avi Weiss (Livneh), provides the readers with a highly professional recounting of how intel for operations should be collected in general and how it was collected in light of the tremendous difficulties in this instance. In fact, the commandos left Israel for the operation with two- or three-day-old information and had no way of knowing if anything had changed in the interim (for example, if the kidnappers had moved the hostages to another building). On the other hand, the gathering of information ahead of the Entebbe Operation required ingenuity and resourcefulness, from collection of maps and data from Israelis who worked in Uganda in previous years, to sending David, a Mossad undercover operative and a pilot, to take photographs of the terminal from the air.

Fourth: the military’s high command and the political leadership. They were the ones who bore the responsibility, each in his own field, and they’re the ones who would’ve carried the burden of failure on their shoulders had the operation not gone according to plan. After the Hercules planes took off for Entebbe, Rabin asked his chief of staff, Amos Eran, to draw up a letter of resignation for him—in case the operation failed. “What do you consider failure?” Eran asked. “Over 25 dead,” Rabin responded.

At first, Rabin was convinced that the operation would be impossible to pull off. He changed his mind because of a few reasons, including pressure from his defense minister, Shimon Peres, and the fragments of intelligence that came in. But above all, it was the commanders’ confidence in their ability to deliver. The most important among them was probably Sayeret Matkal’s commander, Lt. Col. Yonatan Netanyahu, to whom the book is dedicated.

Netanyahu’s memory has suffered several blows since the operation because of ego and politics. That was the case when the most comprehensive and thorough investigation of the operation, written by his brother Iddo, was unjustifiably presented as a biased version of events. That was also the case when some tried to minimize Netanyahu’s part in the planning of the operation and in leading it. One know-it-all commentator who loathes the prime minister, Netanyahu’s brother, surpassed himself when he wrote over and over again that Yoni was on the verge of being relieved of his command and that the Entebbe Operation and his subsequent death were what spared him that fate. Except this was simply not true. The head of AMAN (IDF Military Intelligence) at the time, Maj. Gen. (ret.) Shlomo Gazit, one of the best and most honest among the heads of the Israeli intelligence community, testified to that end earlier this month. “There were disagreements within the unit. I called Yoni in for a meeting, but there was no talk about relieving anyone of their command,” he said.

The book deals with Netanyahu’s role and his vital contribution to the success of the operation, among other things. “Yoni walked on the exposed runaway, commanding the troops, with his head held high,” writes Omer Bar-Lev. “It was the right place for the commander of the raid to be. Had he moved close to the building, his line of sight would have been limited, as would his ability to command the forces. These are the seconds that, at times, make the difference between success and failure. Yoni’s quick charge is what motivated the commandos.” The different testimonies also show that almost all of the commandos thought Netanyahu’s decision to risk losing the element of surprise by shooting the Ugandan guards was the right call—and not just in hindsight.

Forty years later, the testimonies of the soldiers who fought in Entebbe demonstrate, more than anything else, the difference between a commando operation that turns into a fiasco and one remembered as legendary.

As reported by Ynetnews